On 25th May, 1895, Oscar Wilde was convicted of gross indecency. On delivering his sentence, the judge said: “It is the worst case I have ever tried. I shall under such circumstances be expected to pass the severest sentence that the law allows. In my judgment it is totally inadequate for such a case as this.” Wilde would be sentenced to two years’ hard labour. On hearing that Wilde had been provoked into bringing a charge of libel against the father of his lover, the act that set Wilde’s downfall in motion, the social theorist and poet Edward Carpenter was downbeat. “Oscar W. has been very foolish (and naughty),” he wrote in a letter at the time — as Carpenter’s biographer Sheila Rowbotham suggests, he was sad to see the “Philistines” winning.

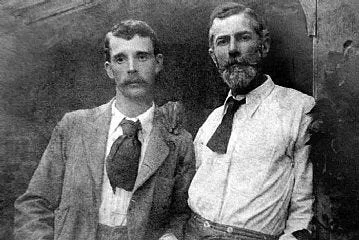

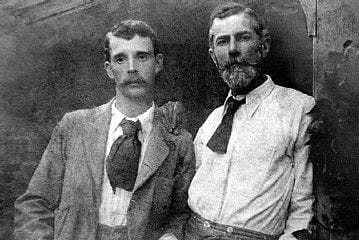

Four years prior to Wilde’s conviction, Carpenter had first spotted the love of his life, George Merrill, on the Totley train. Two decades later, Carpenter would recall how Merrill stood out from the group of men he was with thanks to his “somewhat free style of dress” and how they “exchanged a few words and a look of recognition.” As Rowbotham puts it in her masterful biography of Carpenter, Edward Carpenter: A Life of Liberty and Love, things could have been very different — Carpenter was waiting on the platform for some visitors, and this shared look could have been the beginning and end of the tale. Plus, the pair couldn’t have been more different: Merrill was 22 years’ Carpenter’s junior, he had grown up in the slums of Sheffield, while Carpenter hailed from a well-to-do family. But as Rowbotham tells it, Merrill decided to make a move and trailed the group, and eventually Carpenter fell back to engage this handsome young man in conversation. Merrill suggested Carpenter ditch his guests and come with him to Sheffield, but he was too dutiful to do so. Regardless, Carpenter took Merrill’s name and address before he left.

The pair would remain together for the rest of their lives (though the relationship was never an exclusive one) and would openly cohabit from 1898 onwards. Carpenter — who was raised in Brighton, later studied at Cambridge and spent stints in London — found the first romantic happiness of his life in Sheffield. Which raises some questions: did Sheffield — and Millthorpe, the village nine miles outside of Sheffield where Carpenter resided for much of his life — help save Carpenter from Wilde’s fate? Despite the clichés about London as a tolerant, cosmopolitan metropolis, was Sheffield and the surrounding area actually an easier place to live as an openly gay man back then?

I reach out to Professor Matt Cook, a cultural historian at Birkbeck, the University of London, for some answers. He points out that London in this period was considered the centre of empire — which meant it also doubled as the centre of concern about the generation and loss of empire. “I think there was a very particular worry that at the very heart of the empire, you have this degeneracy and effeminacy.” This, he argues, would have posed a contrast with Sheffield, which didn’t have the same paranoia about a loss of imperial masculinity: “It was a muscular, working class city.” Professor Cook feels this was perhaps part of the problem for Wilde, who wasn’t just flamboyantly effeminate, but part of a movement which ran counter to the Victorian-Edwardian ideal of the progress of civilisation and working hard for the future. “He was part of the aesthetic movement, which emphasised pleasure in the moment.”

Besides, he says. The policing varied between locations, and so the context of London really did make a difference. “Particular divisions of policing in London got the bit between their teeth on this and really pursued it.”

Dr Helen Smith’s detailed study on gay men across England at the time, Masculinity, Class and Same-Sex Desire in Industrial England 1895-1957, also testifies to this point. She explains that one striking aspect about the prosecution of offences like sodomy and gross indecency was that there was a huge disparity in punishments, depending on where the accused was tried, by whom and how the crime was classed. “There was such wide scope in the penalties that could be inflicted for homosexual offences that individual policemen and judges potentially had more influence on the outcome of these cases than in any other type of criminal prosecution.”

When comparing statistics on arrests and convictions for homosexual offences in London between 1880 and 1915 with those in the North, Dr Smith finds that the number of cases in the capital were always at least double, if not triple, the number in the North. “In 1900, northern prosecutions did not even reach double figures out of an approximate population of ten and a half million people. At this moment in time, you would have been unlucky enough to be literally one in a million if you were prosecuted for committing a homosexual act in the north of England.”

Part of this, Dr Smith suggests, is about visibility. London at the time had a flourishing gay subculture that became increasingly visible after a series of scandals that started with the molly houses (pubs, inns or coffee houses where gay men met for companionship and sex) in the 18th century and received a substantial amount of press coverage. This subculture was also geographically concentrated (she argues the non-fiction novel The Sins of the Cities of the Plain could have been used as a guide for a walking tour of homosexual London at the time), in contrast to the North, where a larger population was also spread out over a larger area. Plus: “What has also been well documented is that various heads of the Metropolitan Police took a particular view on actively prosecuting homosexual crime.”

Part of this is purely pragmatic, Dr Smith suggests. Northern police forces had less financing and manpower and as such, dedicated the resources they had to pursuing criminals like burglars and those committing acts of violence, rather than policing a victimless crime like consensual sex. But it’s also about culture. Professor Cook suggests that back then, regional distinctiveness was much more pronounced than now and Dr Smith describes the Yorkshire culture as one which prioritised privacy and was unenthusiastic about the policing of private life in a way which meant that many policemen in the region did not perceive sexual activity between men as a crime.

What strikes me on reading Dr Smith and Rowbotham’s accounts of Carpenter’s life in Sheffield and Millthorpe is that it wasn’t just safer there for a gay man than it would have been in London, it was borderline blissful for the period. Up until Carpenter moved North, he struggled to find a meaningful relationship and felt unfulfilled by experiences with sex workers in London, Italy and Paris. Carpenter was able to find love in the slums of Sheffield and, as Dr Smith puts it, “For a time, South Yorkshire became the epicentre of the world for men who wanted a ‘real’ relationship.” She cites a letter the homosexual poet Siegfried Sassoon wrote after he was forced to leave the army during the First World War after he was injured: “I told them that I want to go as an ordinary worker in some works in a large town. (I have Sheffield in my mind’s eye).”

Carpenter found Sheffield warm and welcoming and quickly became attached to both the place and the people, with the class difference between him and the working-class men he spent much of his time with not proving an obstacle to intimacy. Even prior to his more romantic relationships there, his easy access to casual sexual experiences with men in Sheffield meant he felt at home. Dr Smith notes that there is no evidence that Carpenter ever exchanged money or gifts for sex there, or that he was ever blackmailed, something she calls highly unusual for a middle-class gay person at the time. “Whilst Oscar Wilde…enticed working-class boys into bed with champagne and gold cigarette boxes, men seemed to be having sex with Carpenter for the fun of it.”

Which wasn’t to say that Carpenter’s time in Millthorpe was entirely unmarred by homophobia. As Rowbotham writes, in 1909, he drew the attention of one M.D. O’Brien, a member of the right-wing Liberty and Property Defence League, who was both enraged by homosexuality and socialism and who accused Carpenter of “vice” when he was speaking on ‘Socialism and State Interference.’ While Carpenter was on holiday with Merrill in Florence, O’Brien distributed pamphlets in Millthorpe titled “Socialism and Infamy: The Homogenic or Comrade Love Exposed: An Open Letter in Plain Words for a Socialist Prophet to Edward Carpenter M.A.” In the open letter, he accused Carpenter and the visitors to his home of what Rowbotham terms “morbid appetites, naked dancing, corruption of youth, paganism and socialism.” Later that year, O’Brien continued his attack on Carpenter but made the strategic error of accusing the local vicar of colluding with Carpenter and badmouthing the entire parish where Millthorpe was situated, something which united the village in support of their resident writer.

O’Brien would later write to the Metropolitan authorities in the hopes of getting Carpenter’s pamphlet in defence of homosexuality, Homogenic Love, banned for indecency and argued he could provide the required evidence to prosecute Carpenter (and by association, Merrill) for homosexual offences. Local police were instructed to investigate the claims. They found almost nothing on Carpenter: one local man saw nothing amiss with the fact that he had seen him with “other gentlemen at times who have been staying at his house walking out on the road with their arms around each other['s] waist.” In contrast, there was a long list of conquests on Merrill’s part — the reporting on his failed attempts at seduction is particularly striking. As Dr Smith puts it, even though Merrill’s attempted seductions largely happened in public, these men’s reactions to being interviewed by the police suggests they still considered his advances a private matter that the authorities shouldn’t have been involved in.

A 23-year-old named Allsopp had told O’Brien about Merrill’s advances, but refused to give a statement to the police, saying that what he told O’Brien was in a confidential conversation and he had expected it would be treated as such. He also claimed that “no impropriety took place.” A local man William Platts stated that a decade earlier, when working in the fields with Merrill, he had “exposed his person to him” but he had never gone to the police and refused to talk about it when asked about this. James Markham, Richard White, John Wint and John Walker were all interviewed but refused to give any information.

In the end, nobody was prosecuted. This was probably due to reluctance on both sides — on the part of Carpenter’s community to implicate him or Merrill and on the part of the police, both out of doubt that they would be able to secure witness statements and not wanting to generate a scandal.

One other factor should also be considered, Professor Cook argues. He believes that Wilde could have been apprehended on countless occasions before he was and that both Wilde and Carpenter were pretty open about their sexuality. But both were upper-middle class men: “I think there was a kind of network of privilege which protected men like Wilde and Carpenter.” He also believes Carpenter was protected by the fact that unlike Wilde, he celebrated a sort of conventional working-class masculinity and echoed it himself, sporting a beard during what he refers to as the Victorian-Edwardian beard boom. “He looked relatively like other men in a way that Oscar Wilde didn’t.”

Perhaps more pragmatically, there was also the example of Wilde himself that stopped Carpenter from following the same path. While Carpenter had been horrified to discover O’Brien’s distribution of the pamphlets in his home village, he sensibly took his solicitor’s advice not to sue him for libel. It’s hard to imagine that the memory of Wilde didn’t play into that reaction.

***

Was Sheffield and Millthorpe the making of Carpenter? It’s a big claim, but one I think has merit. Carpenter was clearly an extraordinary man who would have excelled anywhere, but up until his move to Sheffield, Carpenter was lonely, neurotic, downcast. In reading snatches of letters between Carpenter and Merrill, it’s easy to feel the warmth he must have found in Sheffield. Carpenter is addressed as “My Dear Faithful Dad” and Merrill explains he’s been thinking of Carpenter all night. This intimacy extends beyond just the pair of them: as per Rowbotham’s biography, when Merrill is laid up in bed with dysentery in 1893, Carpenter’s ex, the Sheffield razor-grinder George Hukin, stops by after work with cornflower blancmange for Merrill, asking “How art ta lad?” Dr Smith argues that Towards Democracy, the prose poem Carpenter wrote while living in the North, was inspired by the lovers he found there and men he interacted with. It also, I think, gives a powerful sense of someone being set free after many years of loneliness and self-doubt. Sheffield wasn’t just safer for Carpenter — but happier, too.

Not by running out of yourself after it comes the love which lasts a thousand years.

If to gain another's love you are untrue to yourself then are you also untrue to the person whose love you would gain.

Him or her whom you seek will you never find that way - and what pleasure you have with them will haply only end in pain.

Remain stedfast, knowing that each prisoner has to endure in patience till the season of his liberation; when the love comes which is for you it will turn the lock easily and loose your chains -

Being no longer whirled about nor tormented by winds of uncertainty, but part of the organic growth of God himself in Time -

Another column in the temple of immensity,

Two voices added to the eternal choir.

— Extract from Part Three, Towards Democracy

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.