One does not stumble into becoming a fryer. Much like the other kind of friars, it’s a vocation. ‘I always dreamt of being in chips’, says Dani, who runs New Cod on the Block in Walkley. Dani lived next to a chip shop when she was a kid, and even back then, she knew she wanted to have one of her own. Likewise, when I ask Manni and Preet of Four Lane Fisheries in Hillsborough how long they’ve been in the business, Preet starts to work out some sums in her head, then shrugs and just says: ‘my entire life’.

Richard Pearce and his wife Nicola, who run FryMaster in Attercliffe, met working at a chippy when they were only 16 — meaning Richard, who’s 58 this year, has been in the business for over 40 years. He professes to have never been academically-minded, telling me he left school with no qualifications and ‘went straight into the fish and chips game’.

You don’t learn to be a fryer from a manual or a training course, and you can’t automate the process like a fast food chain. There are too many minute variations — in fish, in fat, in potatoes — to standardise the process. ‘All potatoes cook differently,’ Richard says. Some varieties float at the top when they’re done, others don’t. Richard never sets a timer for his chips, judging when they’re done by sight alone. ‘Anyone can cook,’ he tells me, ‘but the trick to being a really good fish fryer is being consistent. Serving the same product day after day, year after year’.

Easier said than done. In Sheffield alone, several beloved chippies have closed their doors in the last couple of years: Tony’s Fish and Chips (2025), Greystones Fish Bar (2024), Papa’s Fish & Chips (2024), Richmonds Fisheries (2023), and Poseidon Fish Bar (2023), to name a few. Crowded out by competitors, pummelled by skyrocketing ingredient and utility costs, and impacted by policy decisions such as the shift from polystyrene to cardboard boxes, the trade is in peril.

Fried fish was introduced to the UK by Sephardic Jewish immigrants coming from Portugal, Spain and further afield, then settling in the East End of London. The first shops selling fish and chips together were in London and Manchester, but it was industrialisation that made the combination the national food. Trawling boats in the North Sea ensured a plentiful supply of cheap fish, and newly laid railways facilitated the swift transfer of fresh ingredients. And, from the outset, chippies provided factory and mill workers with nourishing and inexpensive food – cementing fish and chips as a staunchly working-class dish. ‘They’ve always been a treat at the end of the week for the family when you don’t have too much money’, Richard says. Punters tell me that some days, Attercliffe factory workers still queue out the door of FryMaster for their tea.

But cod, which is by far the most-consumed choice at chippies around the country, is no longer a cheap and plentiful fish. Thanks to climate change, overfishing, the war in Ukraine, and quotas, cod prices are the highest they’ve ever been, and are set to increase by up another 20% this year. The fundamental promise of fish and chips – a cheap and cheerful family favourite – is getting harder and harder to keep.

It’s noon on the dot on a miserable Friday in January when I first visit FryMaster in Attercliffe. A large team is assembled behind the counter, batter spattered up and down their black uniforms. A swinging glass door at the back obscures a large dining area which is already half full. In the dim lighting, I could be in a seaside town in the ‘90s.

Richard, a wiry man in his 50s with a ponytail and goatee, comes from a long line of fryers — so long, in fact, that he can’t remember the relatives who started it all. ‘Rumour has it, they came from Skegness’, he confides in me. His great aunt Eliza opened the first shop in Sheffield. She was on Richard’s dad’s side of the family, but Richard says his mum taught him to fry when he was 15. The youngest of six children spaced nine years apart, he was born in a three-bedroom family flat above his parents’ chip shop in Attercliffe.

When his dad died in 1999, the siblings each took over one of the shops he had across the city. Richard managed Woodseats Fisheries, for a time, then started running another shop, Robin Hood’s Bay, in Attercliffe. Shuttling between the two became too much; he was so busy managing both businesses that he struggled to see much of his son Tom. So he started looking for a large premises that he could own outright. An unusual opportunity came up in the form of the Omega Sauna; Richard got a tip-off from CID guys who used to come in for lunch that the Serious Organised Crime Agency had seized it. He snapped it up before it could even go to auction.

Richard’s wife Nicola comes to take my order and chat. Her auburn curls are pinned back in a messy updo, and she’s wearing sensible trainers, enabling her to move fluently between all the booths, speaking to diners with an easy familiarity. When I ask for the plaice, she also urges me to try the fishcake: it’s a Yorkshire tradition, and not always easy to find. ‘People come here especially for it’, she says. Back in her teens, when she used to work as a ‘Saturday girl’ at Richard’s dad’s place, her favourite meal was a fishcake butty. ‘You can poke holes in it, cover it in vinegar and have it on its own’, she says.

A Yorkshire fishcake is nothing like rissole, Nicola explains. Rissole patties are made of mashed potato, whereas the Yorkshire fishcake is two potato scallops with cod in the middle, then battered and fried. She introduces me to two regulars, Ken and Steve. While they tend to both order the cod, they will sometimes go for a fishcake. ‘It’s done the traditional way’, Steve says, ‘with none of that paste’. Steve, who retired eight years ago, has been coming to FryMaster for almost ten years, and Ken has been joining him most Fridays for at least five, driving over from Handsworth (‘Right behind the Asda!’). Both say they come to FryMaster for the quality and fair prices. Another regular, sitting across from me, tells me he’s been driving to FryMaster from Ecclesfield every couple of weeks for years now, because, he says, ‘the food is proper’.

When my food arrives, I am overwhelmed by a huge cut of plaice, cooked to order and encased in a gleaming crispy batter. The fish is tender and moist and hasn’t been cooked a second more than needed. Draped over excellent chips, which I later learn are fried in beef dripping, I also try a salty and earthy cod roe patty; and finally the fishcake, which, for all its fame, I can’t manage more than a bite of and pack away in a to-go box. I wash my meal down with a generous portion of sweet tea, which arrives in a large steel pot. I don’t know if it’s the atmosphere, the warmth of the dining room contrasting with the cold outside, or just the quality of the ingredients – this is definitely one of the best plates of fish and chips I’ve ever had.

Andy, the Tribune photographer, and I arrive at New Cod on the Block on Commonside around 2.30pm, just as it’s closing. It’s Andy’s local and Dani, the owner, tells us to come in so she can close the blinds and keep random punters out as she starts cleaning up. I start to explain that I’m writing about chippies in Sheffield and she cuts in right away. ‘It’s a struggle,’ she says, and offers me a can of soda.

Dani chats away, whilst never skipping a beat in her close-down routine behind the counter. She tells me she lived in Leicester before getting married. After moving to Sheffield, she and her husband bought Broomhill Friery in 1990 and owned it for over a decade before opening the Ranmoor Friery. ‘Things were good’, she said. They eventually opened their Walkley spot in 2016, but since then, ‘prices have gone up, up, up’.

She pinpoints the moments costs really soared as taking place after the Covid reopening. ‘Oil is fiercely up,’ she tells me, saying it has basically tripled in cost since she’s been in the business. Potatoes – well everyone thinks potatoes are cheap, she says, but they’re £12 a bag as standard nowadays, when they used to be £3 to £4. Then there’s the fish. ‘Fish is like buying gold now’, she says. She has a fresh fish supplier from Hull she works with to get a good deal, but it’s still hard. There are other operational costs to factor in, too: VAT costs are worrying, and she’ll pay thousands in gas and electric.

But people still expect fish and chips to be cheap. ‘Fish and chips is a comfort food’, Dani says. ‘A fast food, not a restaurant.’ She feels bad thinking it might cost over £30 to feed the whole family, so she refuses to raise prices and has reduced portion size instead. ‘Don’t overfeed’, she says. She gives out smaller quantities, and fewer chips, but points out that historically, portions used to be huge — too big to finish, a lot of the time.

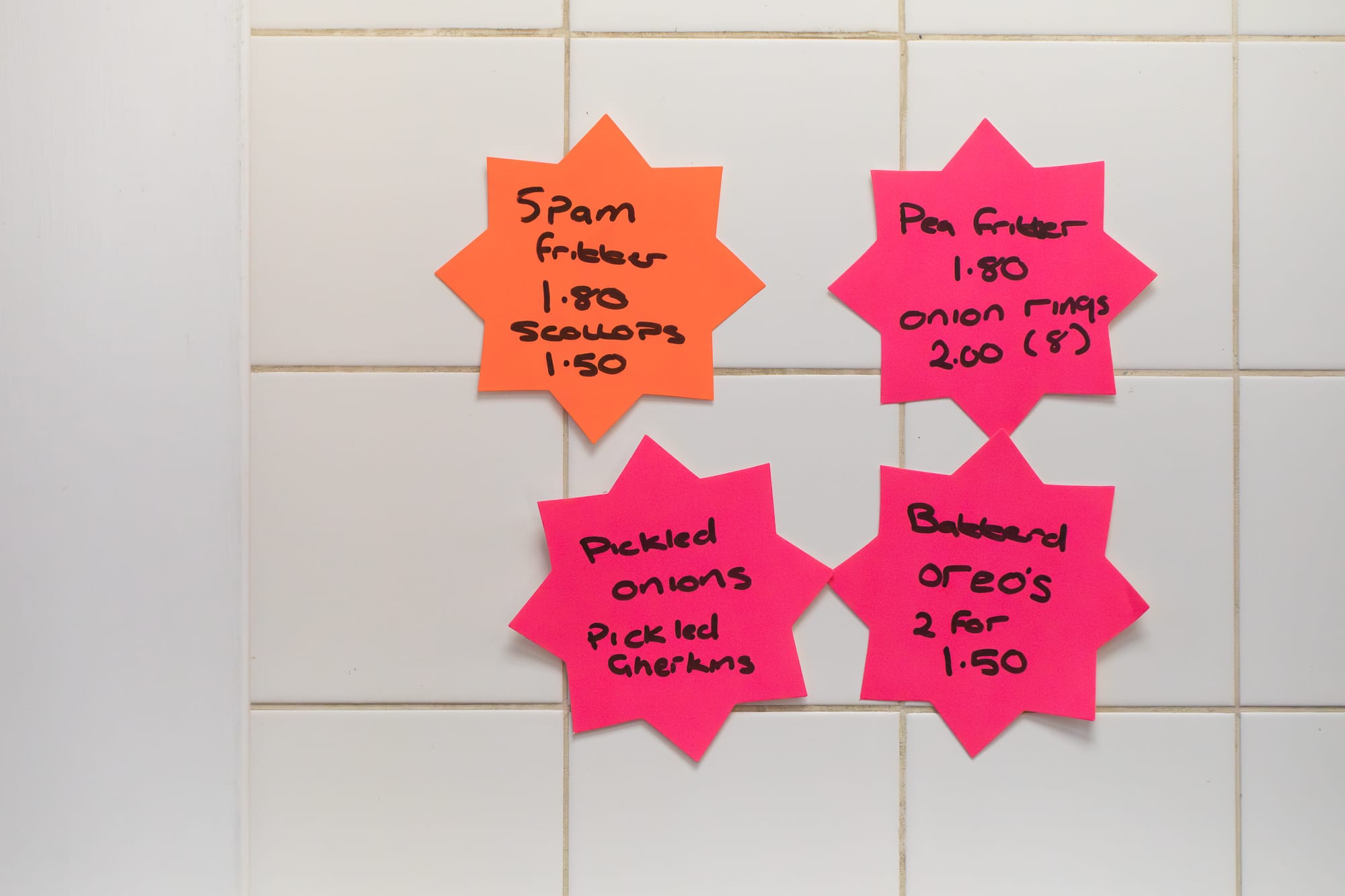

Despite Dani’s eldest son helping full-time, and having no other staff costs, Dani has decided she can’t go on. The shop is now on the market. She’s going to miss it, she says, but ‘people aren’t able to make a living any more’. Anyone she sells the shop to, she believes, will have to diversify: ‘Chinese food, maybe’, she says. I notice she’s selling burgers and doner.

While Richard agrees that things became a lot harder after Covid, he thinks things started changing even earlier than that, with the extension of pub hours. Fish and chips used to be the go-to meal when pubs closed, he points out. The later closures of pubs did affect trade, as did the wider variety of food available on the high street. ‘The go-to became a kebab, and now it can be anything, burgers or pizza.’ Fish and chip shops have adapted, and tend to close mid-afternoon, or at 8pm at the latest. Richard’s shop in Woodseats used to serve until midnight. Frymaster, despite doing a brisk trade, closes at 2.30pm most days.

Like Dani, Richard has seen his energy bills triple over two years. The beef fat they use for cooking chips has increased 50%. He corroborates her assessment of potatoes. ‘There’s been a 100% increase’, he says. ‘Now that the prices have gone up, they’re not about to go back down.’

He says everyone feels bad charging more. Charge too little, though, and your profit’s gone. He says Richmond Fish Bar closed due to financial pressure, as did Darnall Fisheries. ‘The pricing took them out of the takeaway game,’ he says, ruefully. ‘Fish and chips is no longer the go-to cheap takeaway.’

Unlike other chippies, Richard refuses to diversify. He will not be selling kebabs, he says. He knows he’s got a winning formula and he’s willing to stick it out. ‘There’s a reason we do things the way we do’, he says, ‘and that’s because it works’.

At FryMaster, prices now change once a year. In the interim, Richard focuses on absorbing costs and offsetting them by increasing the number of customers. Last Saturday, he says, was the busiest they’d ever had. ‘People can, and will, travel for good fish and chips’, he says. And in December, lots of regulars came in with Christmas gifts for the staff. Richard acknowledges the reality that loads of businesses are closing. ‘But’, he says, ‘those left standing will be stronger for it’.

Dani says her shop won’t sell overnight. Once it does, though, she plans to take a year out to travel the world. Then she’d like to teach or run training for new food businesses. She certainly has the expertise; knowledge absorbed over years like chip grease into clothing. But will anyone want to learn?

FryMaster’s dining room is dominated by a large print of a Joe Scarborough painting. Commissioned by Richard, it’s an affectionate, tongue-in-cheek Attercliffe street scene, an imagined blend of past and future. The Supertram zips across the neighbourhood, while elsewhere police chase after local thugs. FryMaster is clearly visible, and in the background some people are removing a sauna sign. The cooling towers and Forgemasters hover in the background. ‘Joe still comes in’, Richard says.

Attercliffe, like Sheffield itself, has had many lives. I scan the high street for landmarks: the erstwhile Banners’ department store; and local business names: Big Baps, TimeBomb Chinese Fireworks. Now home to Sheffield's English Institute for Sport and Hallam’s Advanced Food Innovation Centre, it's now a focus of council regeneration plans. Richard believes there’s a lot of promise. ‘It’s the main arterial road into Sheffield’, he says. ‘It could be the next Kelham.’ Once there are more houses, Richard hopes, there will be more of a market for independent shops – for new ones to move in, and for existing ones, like chippies, to find a new lease on life.

Chippies will persist, of course: they are too ingrained in Sheffield’s history to be fully phased out, too valuable to lose. But they, like everything else, will have to adapt. It’s not for me to say what that will look like, but I can speculate. Maybe diners will have to give up cod and try other types of fish. Maybe – almost definitely – they’ll need to pay more for a meal. And maybe some chippies will have to diversify, or use apps, or reduce their hours. Some – many – will close. But those that don’t will be left standing stronger.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.