By Daniel Timms

Do local elections matter? We all know the answer should be “yes”, but the stats suggest most people aren’t convinced — fewer than one in three Sheffielders put their cross in a box last year.

There’s no shortage of explanations for why this is the case. As a country, much of the serious power is concentrated in Whitehall. With far less substantial local media coverage than its national equivalent, people are less engaged in the workings of their council than they are in the workings of Downing Street.

Most people do care about local issues — the quality of schooling, planning decisions in their neighbourhoods, the state of local parks, and whether they feel safe on the roads. And yet some people probably feel that they don’t understand enough about the differences between parties to make an informed decision.

That can feel especially true in a city where the governing party at the national level has virtually no foothold. When we see them on the news, the Westminster leaders of the Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green parties are often united in their opposition to government policy — but that can make it more difficult to see what distinguishes the parties at a local level.

The recent history: Labour losing control

There’s another reason why people don’t vote at the locals — confusion. Many don’t understand how the local electoral system works and the different tiers of local government can be baffling. With apologies to those in the know, let us begin with a quick overview.

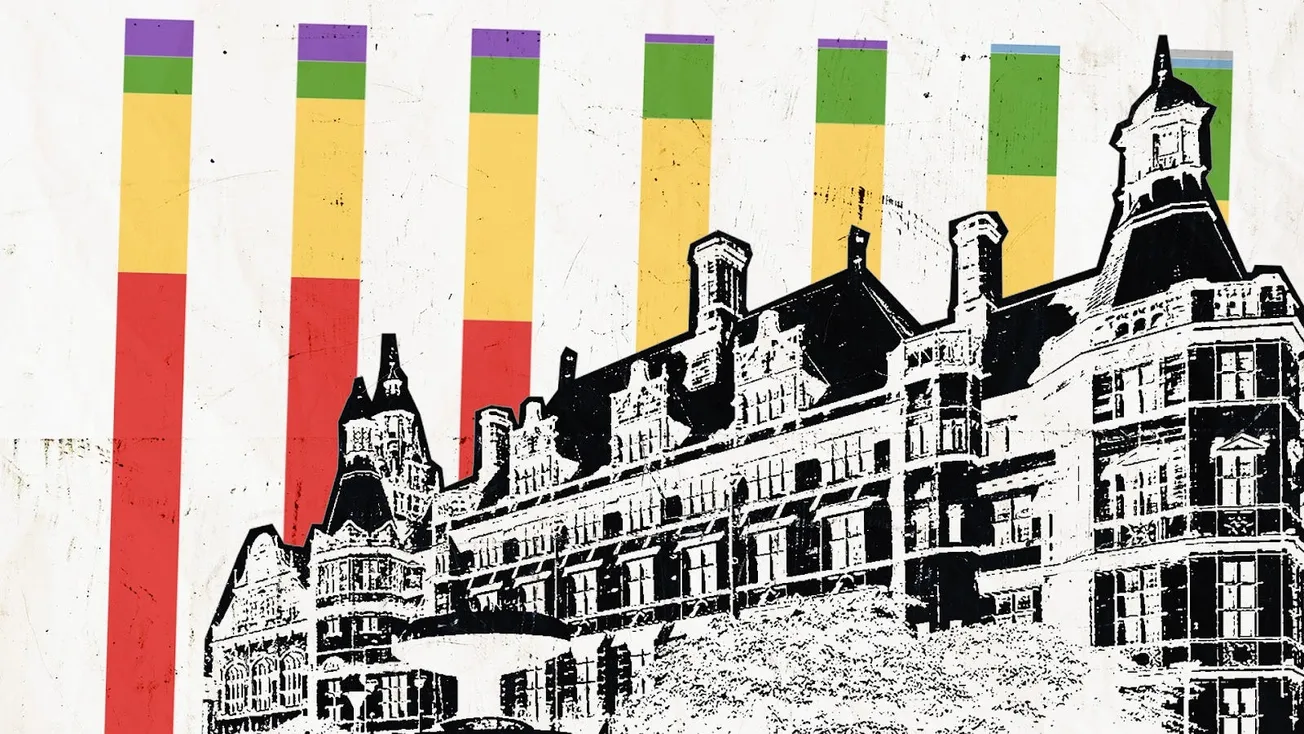

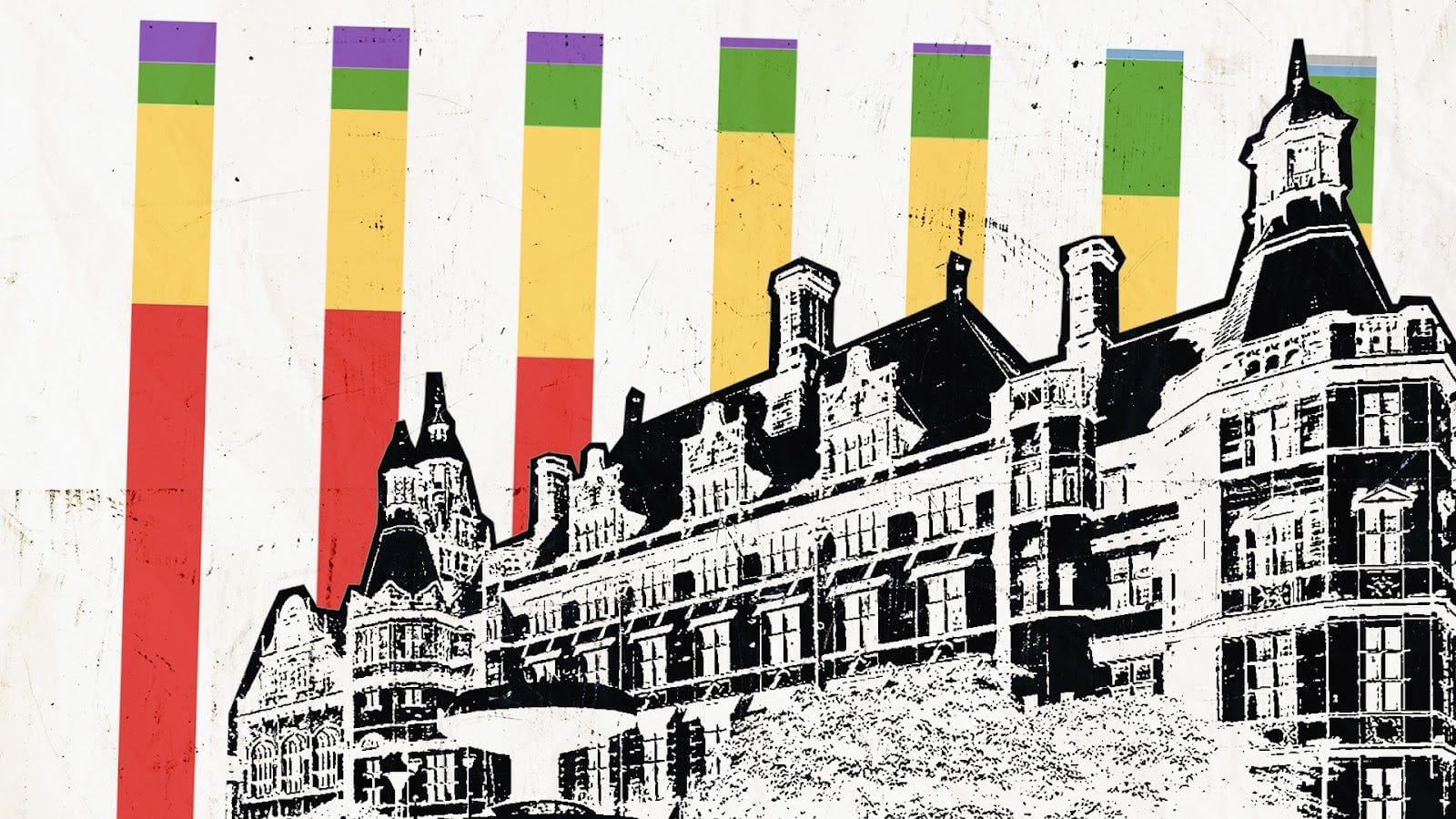

Sheffield is split into 28 wards (find yours here), each of which elects three councillors, giving 84 councillors in total. Sheffield runs a “thirds” system where for three years in a row everyone gets to vote for one of the seats in their ward on a rotating basis. In the fourth year we get a break from this frenetic democracy, and the council membership remains unchanged.

This system means that instead of dramatic election nights where everything changes, the make up of the council shifts more gradually. Nonetheless, the trend for the last few years has been pretty clear, with a falling share of Labour seats. In 2021, the party lost overall control (no longer having half the seats plus one) with the Lib Dems and Greens both gaining ten seats between 2016 and 2022. Sophie Wilson, previously a Labour councillor, handed in her party membership last year and sits as an independent.

Put the current composition of the council on a map, and you can see there are some broad geographical voting blocks. To the east are the Labour heartlands, to the west the Lib Dem strongholds. Sandwiched in between are the Greens, who have been slowly but steadily prising seats from Labour’s grip in areas like Gleadless Valley and Broomhill. There are a couple of other Lib Dem outposts in the North East and South East, while in Stocksbridge (the most north-westerly ward) sits Sheffield’s only Conservative councillor (alongside two Labour councillors).

Finally, there is an elected mayor — currently Labour’s Oliver Coppard — who covers not just Sheffield but South Yorkshire a whole, including Rotherham, Barnsley, and Doncaster as well. There’s no mayoral election this year, but parties will need to work with him on their bigger ideas — he has powers over areas like transport which only he can exercise.

So what are the policy differences? I asked a representative from each of the three main parties (who between them control 82 out of 84 seats) to set out their priorities. Perhaps you will not exactly fall off your seat in surprise to hear that many themes were common! But there were still some important, if subtle differences…let’s dive in.

Labour: Public transport and affordable housing

Labour is one of the two parties to put out a manifesto, and they’re not messing around — it’s a relatively hefty document for a local election. “Our Plan for Sheffield” sets out some eye-catching policy ideas, including introducing a net zero test for all policies, producing a local industrial strategy for the city, creating a “Gallery of the North” as a flagship art space, and a damp and mould taskforce to improve council homes.

I spoke to Tom Hunt, Labour Councillor for Walkley, to hear more. The first point he stressed was public transport. “There are so many parts of Sheffield which have been underserved by current bus routes — it’s something we’re hearing about time and time again”, he tells me. The Labour mayor has begun the process of taking buses back into local control, and the SuperTram network will soon be in public hands. Having them both means that public transport can be integrated, which Hunt argued will remove one of the major barriers that keeps people out of work (a topic we covered recently).

The other area where he saw a clear difference with other parties was on the provision of affordable housing. Labour is arguing for an ambitious target of 3,100 affordable council homes over the next six years. At this point, I pushed back — affordable homes delivery has been below target during the Labour majority years, and as acknowledged in a recent write up of the housing committee, rising inflation is making this more challenging than ever. Hunt acknowledged that the overall housing budget might need to be reviewed to achieve this, but objected to what he saw as other parties lowering the ambition.

The Housing Committee (which is chaired by the Greens, though has members from all parties) has reduced the target by 800, and he quoted a Lib Dem spokesperson as saying it might be better to “tread water” on this issue for the time being. He cited an example of a former care home site in Walkley that’s “ready to go” and argued the council can make progress if there’s the will to do so.

Lib Dems: Financial sustainability and communities

“Sound financial management” is how Lib Dem leader Shaffaq Mohammed begins, when asked what his party will stand for in Sheffield. He sits on the council’s finance sub-committee and hits out at what he sees as overspending from previous Labour regimes. He also takes credit for an amendment that set a balanced budget this year.

When I challenge him on what has had to be cut in order to balance the books, he refers to cuts in social care services, though he argues this is more about savings that weren’t being previously taken advantage of. At the same time he argues for free bus passes for young carers and a council tax rebate for those with caring responsibilities: “We’d like to look after those who care for others”.

The Lib Dems have also published a manifesto (“Getting Sheffield back on track”). It’s quite detailed, and in some places pretty technical (“We will oppose the inclusion in the Local Plan of a ban on new hot food takeaways within 800m of a senior school as this will prevent such establishments locating in many of our shopping areas”) but perhaps the biggest idea is to devolve more powers down to local area committees — which cover smaller parts of the city. He believes that giving these groups more powers over funding (for example, for roads) will improve outcomes and increase people’s sense of engagement in the democratic process.

People don’t trust the council, Mohammed believes, and he insists the current leadership are unable to rebuild it in the wake of the Lowcock Report (into street trees). His pitch to voters? That the Liberal Democrats are the only viable alternative to a discredited regime.

Greens: Climate change: housing and transport

For Douglas Johnson, leader of Sheffield’s Green Party, environmental policy is more than just a solution to the climate crisis. “What’s good for the climate is good for people”, he tells me, and points to retrofitting housing as a policy priority. This, he believes, can cut both carbon and bills, while improving people’s quality of life — though he’s happy to admit that rolling out these initiatives in private housing is a logistical challenge to say the least.

Environmental issues, including biodiversity, make up the main bulk of our conversation. Johnson takes credit for Sheffield’s adoption of a ten-point plan for climate change, and believes that while the city is aiming in theory for net zero in every policy, the reality is more mixed.

Bike lanes and bus lanes are clearly a real hot potato — an area where the Greens have been the most outspoken in arguing for restrictions on cars. Both Labour and the Liberal Democrats have blamed the Greens for what they see as failings in rolling out “active travel neighbourhoods” — in particular, that not enough was done to consult people before their implementation.

While Mohammed (Lib Dem) used our conversation to highlight business concerns about losing custom from traffic reduction schemes, Johnson argues that the Greens are representing the 30% of Sheffielders that don’t own a car.

The Greens haven’t published a manifesto specifically for this election, though a press release about the launch of the campaign is available here.

The big question: Can Labour win back control?

On the face of it, the numbers look good for Labour — they’re only a few seats away from a majority, and the national polling figures suggest the party is doing well. Sir Keir Starmer and his strategists will be deeply disappointed if the city doesn’t turn red. But it’s not so straightforward in Sheffield for two reasons: the opposition, and — yes — trees.

Firstly, Labour aren’t really up against the Tories in Sheffield, so to the extent that the national polls express people’s dislike of the government, that dislike may translate into less of a local advantage here than it would in areas where the Conservatives are a serious force.

And second, the election follows hot on the heels of the publication of the Lowcock Report into the street trees scandal. That killer line in the report – “a serious and sustained failure of strategic leadership” – was mentioned more than once in my conversations for this story. Has the report had a wide enough audience to re-ignite anger at Labour in Sheffield just ahead of next week’s elections?

A few candidates are standing purely on this issue. Justin Buxton, standing as an independent in Terry Fox’s ward, was a veteran of the street tree wars (“I was arrested several times”, he reminisces). When I asked whether he was there to provide a protest vote option, he was unambiguous: “Yes. It’s principally about the excoriating findings of the Lowcock Report, but it goes over into issues of accountability within the council”.

If Labour regain control, it could also mean a change in how the council is run. As long-time Tribune readers know from our coverage of the story at the time, about a year ago Sheffield switched to a “committee system”, where instead of decisions being made by an all-powerful cabinet, council committees are king and they have representation that reflects the political make-up of the whole council. It’s supposed to bring about a more open and constructive style of working, and since Labour lost its majority, every major policy has needed the support of at least two of the parties.

The committee system isn’t going anywhere, and all those I spoke to were in favour of it. But some worry about a Labour majority administration, with the party running every committee.

Ruth Hubbard and Woll Newall are members of the Sorry Not Sorry campaign, which has come together following the Lowcock Report. Hubbard believes we’ve seen “small but important gains” in consensus decision-making in recent years — and believes the report shows how toxic one-party rule can be. “There’s an autocratic strand in Sheffield Labour thinking”, Hubbard believes, and Newall argues that “we’ve had the technical change [the committee system]... but there’s been fifty years of building this dysfunctional political culture in Sheffield — that won’t change quickly”. On their website, they publish tactical voting advice for those who want to prevent one-party rule.

So how well has Sheffield Council worked without overall control? Johnson, the Green leader, pointed me to the long-awaited publication of the draft Local Plan as a sign that more progress is being made now — with previous Labour administrations too concerned about the reputational fallout of doing unpopular things. Hunt, from Labour, disagrees: “People are missing out on a council that puts people first. The voice of the city is not being heard as loudly as it should be.”

Democracy in action

Politicians tend to say that the upcoming election is the most important one in living memory, but the truth is that some matter more than others, and that’s true for local ones too. For what it’s worth, I think 2023 will be quite consequential for Sheffield. Labour have their best chance of taking back control since 2021. If there is to be an electoral backlash following the Lowcock Report, this would be the year. And while they hold much in common, the main priorities of the parties are notably different.

It would, of course, be below the high standards of the Tribune to tell its readers how to vote — we’re here to stimulate thought, not replace it. No doubt there will be strong views expressed in the comments, and we welcome the debate.

But when only one in three vote, those that do hold more sway. An engaged populace gets better politicians — and that really does matter.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.