Smoke-filled pubs strewn with pints of foamy ale as the sound of snooker balls clack. Bickering around a family dinner table over clinking tea cups. The camaraderie between miners on a snap break down a shaft as they munch on jam sandwiches. The mud-caked knees of school boys running around a football field. The seething rage against the politically unjust. And, set against churning smog: piles of coal, and landscapes of lush green.

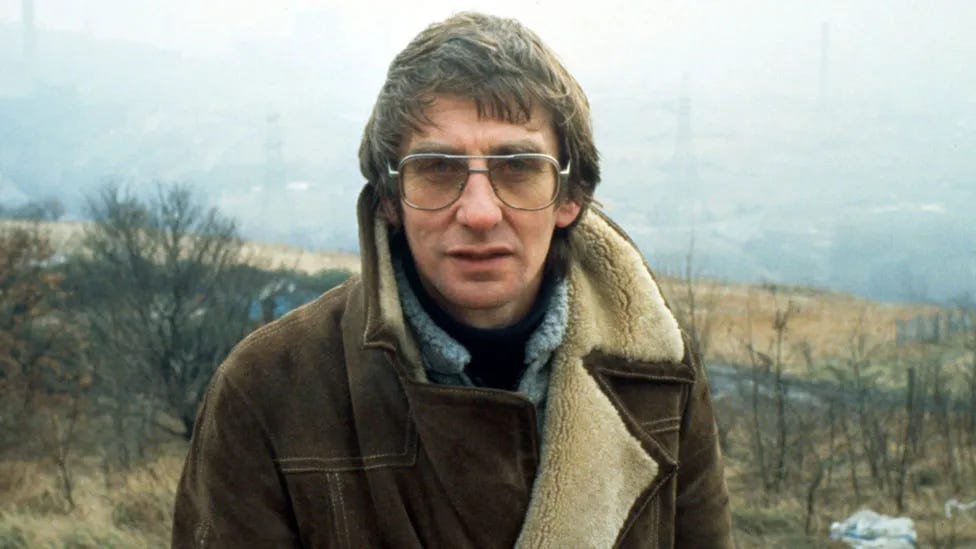

There are few writers who have managed to capture the tongue, spirit and essence of post-war South Yorkshire quite like Barry Hines. The writer of novels such as A Kestrel for a Knave, The Gamekeeper, Looks and Smiles, and The Blinder – along with TV and film scripts such as Threads and The Price of Coal – Hines was a working class writer who sought to capture everyday life with artistry, authenticity, and comic flair.

After Hines’ death in 2016, the filmmaker Ken Loach described him as “a writer of clarity, economy and depth who was describing a world so familiar, yet largely unrecorded”. It’s easy to assume that the reading public admires Hines every bit as much as Loach does. His most critically-acclaimed novel, A Kestrel for A Knave is a Penguin Modern Classic, telling the tale of Billy Casper, a young boy alienated from school who develops a self-taught skill of falconry (loosely based on Hines' own brother, Richard). You may even have studied it as part of the O-Level / GCSE English syllabus. Just as the likes of Jarvis Cocker did, which had a life-changing impact on the Pulp singer who loved the “symbolism of flight and of escape from your surroundings…that was very powerful for me growing up.”

But the more I think about Hines, the more it’s obvious that a lot of his work remains criminally under-appreciated and under-recognised (or not even associated with him). Thankfully, this seems poised to change, with signs suggesting that we might be on the verge of a renaissance of interest in his work. Could this be the year that we start to recognise Barry Hines for the breathtaking work he wrote apart from his most famous novel?

Hines' trajectory in the writing world was a unique one. He was the son and grandson of a miner, growing up in the village of Hoyland Common in the 1940s and 50s. Passing his 11-plus exams, he was thrown into a grammar school environment he disliked, immediately picking up on inequalities in the education system which stayed with him, and in his work, throughout his life. “Education reflects the class system, and the system has to change before education can,” he later said.

A brief stint as an apprentice mining surveyor didn’t last and upon returning to school he excelled as an athlete and footballer before going on to study to become a PE teacher at Loughborough University. It was here, age 21, that he read his first book: George Orwell’s Animal Farm. A love of Hemingway's simplistic prose soon followed and he "caught the bug” and began writing bits himself.

For his final year dissertation he remarkably opted to submit a piece of creative fiction about “the physical and mental world of physical education from a personal emotional angle, through the thoughts and attitudes of one boy, Jack Barlow.” He later remarked: “I didn’t know how the hell they accepted it. Because it was nothing to do with physical education, but I couldn’t stand the thought of doing the usual thesis, you know, esoteric subjects like the roll of the intercostal muscles in weightlifting and all that carry on. They were so astounded, they didn’t dare fail me.” Hines got a B for that outlandish move but it proved to be the basis for his 1966 debut novel, The Blinder, arguably laying down the foundations for his entire career.

Prior to the release of The Blinder, the first thing Hines wrote with any real purpose was Billy’s Last Stand, a play about a coal shoveller who gains a nefarious rival. Hines initially wrote it “with no medium in mind, and at epic length” before sending it to Alfred Bradley, head of Northern BBC radio drama. It was then turned into a radio play, received rave reviews, and soon Hines was being offered literary representation.

Bradley became something of a mentor to Hines and helped him secure a grant that allowed him to take time off work to focus on finishing A Kestrel for a Knave. The film producer Tony Garnett had already been in touch with Hines after hearing Billy’s Last Stand and wanted to work with him on a play. Hines passed, saying he had a novel he needed to finish. Garnett asked if he could send on said novel once he had completed it and so Hines duly did. Garnett, and his filmmaking partner Ken Loach, were so impressed they bought the rights to make it into a film before it had even been published. Positive reviews of the book followed and so too did a piece of work that would change Hines’ life, as he soon found himself on a film set bringing his words to life for a future classic piece of cinema.

Parts of the film were shot back where it all began for Hines, in Hoyland Common, where he used to climb coal heaps as a child. Coal – and what it represents – runs through Hines' work in a very literal and metaphorical way. It remains such a powerful and consistent presence that you can almost feel the blackened dust of it on the pages as you turn them. From the very first lines of Billy’s Last Stand to the central unspoken character it plays in the 1977 two-part TV drama he wrote, The Price of Coal.

Hines seemed to loathe and respect the pit with equal measure. He was aware of its harsh, brutal environment – one that took the life of his own grandad – and resentful of the often solitary work option it presented to young people who may possess more skills and talent. He seemed equally aware of how they could be a tool for political manipulation by greater powers to endanger and undermine workers. But he also captured, and clearly revered, the close-knit sense of community that took place around them. “Barry understood class politics,” Loach said of him. “The irreconcilable conflict between workers and employers.”

Speaking today via phone, Loach — who recently announced his retirement from filmmaking aged 87 — further reflects on his relationship with Hines. “I loved the truth of his writing,” he says. “He captured the rhythm of [local] language better than any writer I know of or could imagine. He caught the wit of it and grasped it in a way only someone who truly loves it could – and he truly loved the language, people, culture and places of South Yorkshire.”

Loach worked on four projects with Hines, in what he describes as a “happy, collaborative, supportive partnership”. There was of course the indelible classic, Kes. Then The Gamekeeper, about an ex-steelworker employed as a gamekeeper on a ducal country estate to gather birds to be shot by his wealthy employers, which explored themes around land ownership, capitalism and class; while Looks and Smiles depicted the psychologically ravaging effect of Thatcherism in Sheffield over years of declining industry. The Price of Coal, meanwhile, was a two-part TV drama set at a fictional South Yorkshire colliery preparing for a royal visit one day, and dealing with a fatal yet preventable accident the next.

Even though A Kestrel for a Knave and Kes remain the most famous and enduring of Hines’ work, his substantial role in shaping the end product of the film has not always been fully appreciated and documented. This is something that may be rectified by the latest installation in the BFI Classics books series, Kes, by David Forrest, Professor of Film and Television Studies at the University of Sheffield. The book instead positions the film as being a classic example of a triumvirate between Hines, Loach and Garnett, steering away from previous critical and academic studies that frame the film more as Loach’s rather than the deeply collaborative effort it was.

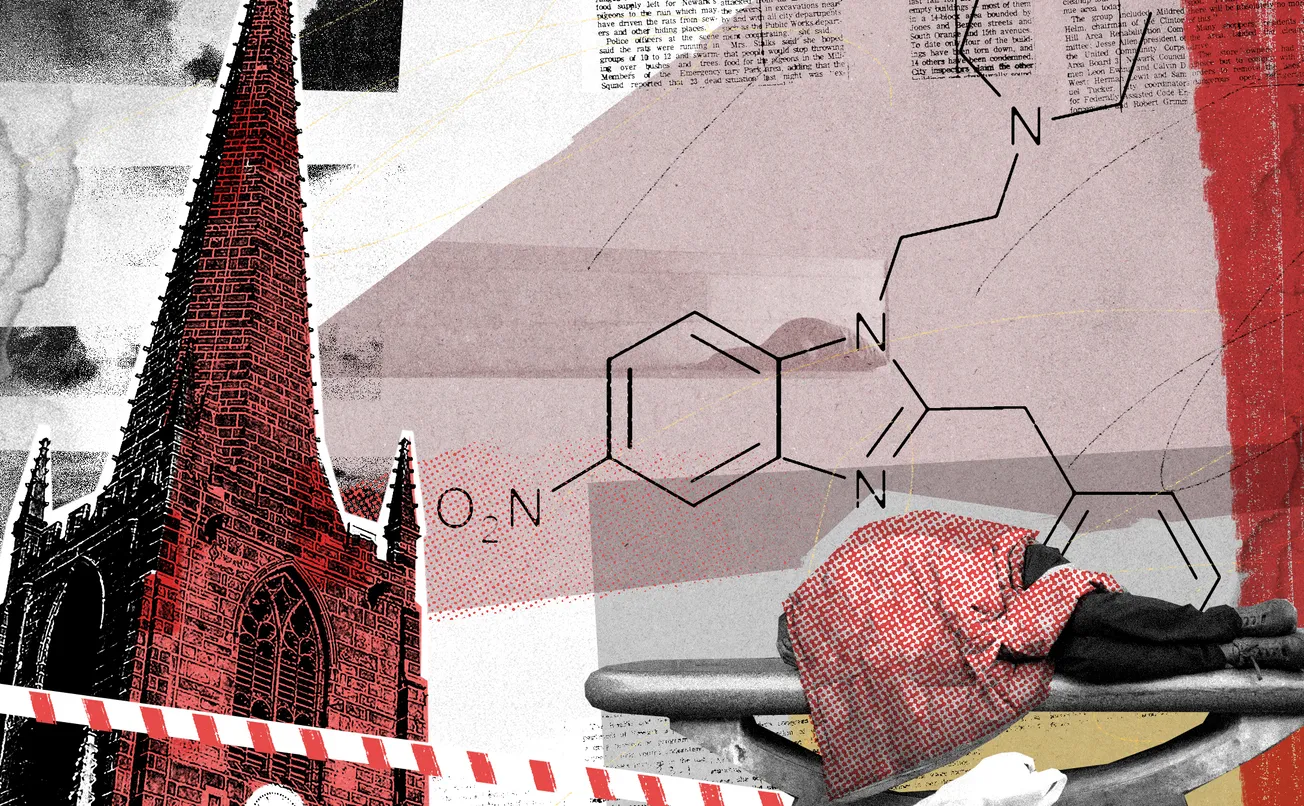

Another of Hines' most celebrated works, the 1984 Sheffield-set nuclear holocaust film Threads, is also in the spotlight this year as it turns 40 years old. A documentary is being made about it, and just this week, an anniversary screening and panel discussion sold out the largest screen at the Showroom cinema.

However, while some of Hines' work still clearly resonates, few people seem to realise that the same person was behind these different works. “People may know Kes or Threads but very rarely do they make the connection between the two,” says Forrest, who also co-authored the 2017 book Kes, Threads and Beyond with Sue Vice, Professor of English Literature at the University of Sheffield. Perhaps such is the nightmare-inducing imagery of Threads that people would struggle to make the leap between the comparatively quaint tale of a village boy and his beloved bird.

These books about Hines, and the continued posthumous focus on his work, has largely been made possible via a generous donation of his professional archive, shortly before his death, by his wife Eleanor Mulvey (who has also since passed). “Otherwise, who knows what would have happened to it,” says Vice. “It might have been just cleared out of his house when they sadly both died.”

The archive, which is available to the public but requires advanced booking, is vast. It features an array of manuscripts, annotated drafts, correspondence, and completed works, both published and unpublished. It’s quite a thrill to hold the hand-written first draft pages of A Kestrel for a Knave, knowing the significance those words and scenes would go on to have in British culture. Reading the original council-issued literature entitled ‘What a Nuclear Attack Would Do to South Yorkshire’ complete with blast radius diagrams and terrifying death stats predictions, adds a chilling yet vital context to the terrorised state viewers were in when they saw Hines' harrowing words and images transmitted on screen.

But while the archive contains vital insights into Hines' classic works, it also shows how much has slipped through the cracks. His final novel Springwood Stars, which concerns a village soccer team during the hardships of a 1920s miners' strike, was completed in 2002, but it still hasn’t been published. Billy’s Last Stand, which was turned into a Play for Today for the BBC, was not preserved and no longer exists. Looks and Smiles is out of print, and the film is currently impossible to watch anywhere in the UK. There are entire film scripts, such as a football film called Injury Time, that have never seen the light of day, while many of his other works also remain out of print or publicly unavailable, such as the sold-out titles published by Pomona Books.

Forrest and Vice are not the only locals trying to keep Hines' legacy alive. In 2022, the Sheffield publisher And Other Stories re-released The Gamekeeper after it had been out of print for years and almost impossible to get hold of. “I jumped at the chance to publish Barry Hines,” says And Other Stories’ publisher Stefan Tobler. “He is clearly one of the most important writers to come out of South Yorkshire, and The Gamekeeper is definitely one of his masterpieces. Its descriptions of the natural world over the course of four seasons is detailed and evocative, while the eye for class conflict and loyalties on a lord's estate is classic Hines.”

The hope for Tobler is that people will begin to connect the dots between Hines' work and realise the scope of it. “He does seem to have been both blessed and cursed by the success of Kes and the novel it came from,” he says. “For some reason, many readers love that novel, but never read more by Hines.”

However, while 2024 may feel like a year that Hines' work is having a light shone on it, there are still parts of it left in darkness. This feels most pronounced when you look at some of this year’s retrospective work around the miners’ strikes, a subject Hines wrote angrily and impassionately about. His 1985 play After the Strike was written around the battle of Orgreave, bursting with a raw, unflinching and staunchly political stance highlighting the corrosive impacts on local communities. It was deemed too inflammatory, was rejected, and never came to life apart from a one-off in 2019 when it received a public read-through in Sheffield to mark the 35th anniversary of the battle of Orgreave.

“He was certainly ahead of his time,” says Forrest. “Especially now that you can see the sorts of narratives illuminated in his plays are visible.” Next week in Rotherham (June 12) the artist Jeremy Deller will bring his reenactment film The Battle of Orgreave (An Injury to One is an Injury to All) to town, and then just days later a new documentary, Strike: An Uncivil War, will receive its world premiere at Sheffield Doc/Fest on the same subject and with an angle that Hines had spent years pushing. Although his tales of police violence and fractured communities remain boxed up.

Hines’ work doesn’t just focus on what we should be angry about, but also on what we should celebrate. A more general yet inescapable recurring theme in his work is his ability to pluck beauty from the ordinary – harnessing untapped potential, as all good teachers can do. Forrest echoes the poet Ian McMillan in his praise of Hines by saying, “one of his great gifts was that he enabled working class people, specifically people in those regions, to feel as though they were recognised,” he says. “He elevated their everyday lives to the status of art.”

Hines' concise yet punchy, funny, and deeply rhythmic ability to mirror the everyday dialogue of people – always written and delivered unapologetically in a thick local dialect, even if American reviewers deemed it “unintelligible” – was a precision skill that could only come from being part of the community he depicted. “It’s not through an anthropological lens,” says Forrest. “It comes from the communities that he is a part of and seeks to represent, so it has that layer of authenticity.”

Yet his depictions are not overly sentimental or nostalgic. They are the equivalent of transporting the backroom of a pub, office, cafe, living room or newsagents onto the page. Loach recalls Hines’ ear for dialogue being so pristinely natural that many people would mistake it as actors going off-script to speak more conversationally but “95% of the time it was all in the script.”

Another part of the dedicated efforts to promote Hines' work is to widen it. “I'm really interested in de-parochialising a writer like Barry Hines,” says Forrest. “We have a tendency to reduce regional work, to really narrow it down and put people in a pigeonhole, and say: this only works for Northern audiences.” The hyper-local focus of a lot of Hines' work can instead have the reverse effect, argues Forrest, who is speaking at the BFI in London in November about Hines and his Kes book. “Hines' great strength is the way he holds together the universal and the specific,” he says. “The specific creates a sense of authenticity and familiarity, while the universal creates that point of engagement for everybody.”

Vice echoes this too. “His work is a local history but all the elements of class and stratification apply equally wherever you go in Britain,” she says. “I think he saw Sheffield as a microcosm for Britain as a whole.” No more so is this approach clearer than in Threads, which uses the everyday realities of a working class city like Sheffield to watch a harrowing nuclear winter unfold after an explosion in Crewe. And in doing so, he tapped into a relatable and palpable fear that shocked a nation into silence when it first aired.

While Hines had his moments of acclaim – Threads won multiple BAFTAs – a feeling of critical decline and disinterest entered into his later years as work slowed down in the 1990s. He continued to explore coal mining as a subject in the 1994 novel The Heart Of It, as well as football in TV plays like Shooting Stars and Born Kicking (about the first professional female footballer) but things were changing. “Simon Armitage wrote a particularly nasty review of The Heart Of It,” recalls Forrest. “What's clear is you've got a Northern writer on the up who just feels what Hines is doing is kind of not relevant. Fashions change."

However, Hines' steadfast dedication to his subjects was unfairly maligned Forrest feels. “Proper social realism has a claim to be one of our really important working class indigenous art forms,” he says. “Although there's this idea that you should then move on to something else more mature – but with Hines it was a commitment and a principle. Looking back, that commitment is remarkable amongst his contemporaries. And quite rare.”

There is also perhaps a case of the terminally humble South Yorkshire trope at play here too in regards to some of Hines' work not filtering through. He was a modest writer who eschewed the London literary world in favour of remaining in Sheffield and continuing to work in education. “Barry walked away from that and good on him for doing it,” says Loach. “It tends to be inward looking and if you're a working class writer, as Barry was, well, it's just not part of their world.” The late producer, Tony Garnett, called him “a worker at the service of other workers.”

So are we about to witness a greater renewed interest in Hines’ words outside of his most famous work? Perhaps on some level. The Gamekeeper is selling well, and there’s hopes of getting his final novel finally published, while the demand was so great for the recent anniversary screening of Threads that it ended up being the cinema’s biggest advance ticket sales since Barbie last summer. Forrest and Vice say their young students continue to respond to his work with great enthusiasm and admiration.

But a lot remains unavailable still. Plus, Hines’ work is also deeply rooted in a very specific time and place, and written in a style that is not currently echoed in the zeitgeist. It’s unlikely he’ll be due a Baby Reindeer moment anytime soon but you also get the feeling that his distinct, powerful and versatile social realist writing was never intended for such widespread, arguably fickle, mass appeal.

Just take his final ever interview, when Hines was asked if he felt like a literary icon. His response feels like a fitting embodiment of how he viewed his writing, its function and perhaps what its legacy should look like. “The Price of Coal was on television one evening,” he recalled. “When I got on the bus in Chapeltown the next day it was full of miners coming off shift. I walked down the aisle and they just looked and said nothing. I’m scared to death until one man appointed himself spokesman and said ‘that were alreight, Barry’. I felt like an icon then.”

Barry Hines: Kes, Threads and beyond by David Forrest and Sue Vice is available from Manchester University Press. The Gamekeeper is available from And Other Stories.

Comments

Sign in or become a Sheffield Tribune member to leave comments. To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.