When Moi Tran was younger, she went to see a new musical called Miss Saigon, set in the final months of the Vietnam War. It had been out for a little while – she had to save up to afford the ticket – and was already a huge success. As a refugee from that war, struggling to get used to life in the UK, she remembers how excited she was to see a musical that would depict her people and her country in a positive light. But Miss Saigon was not that musical, and she left the theatre in tears.

“I have never come to terms with why it’s still being staged,” she told The Tribune earlier this week. “It is harmful, racist, misogynistic and inaccurate.” This is a word she returns to more than once: inaccurate. The problem was not that Miss Saigon touched on painful parts of recent history, the problem was that the characters on stage bore no resemblance to the real Vietnamese people she knew. (As an example of that production’s commitment to authenticity, one Asian character was played by a white actor, with his skin painted darker and prosthetics to change the shape of his eyes.)

This is why Moi, a set and costume designer based in London, was horrified last year when Sheffield Theatres announced their plan to revive Miss Saigon at the Crucible, especially as she was freelancing for a play due to appear at the same theatre last month. “When I found out we would be bringing our show there when [Miss Saigon] would be rehearsing, I was very upset.” The rest of the creative team, mostly East and South-East Asian women, agreed. They cancelled their play last November.

In a public statement at the time, the musical’s co-directors, Robert Hastie and Anthony Lau, conceded that Miss Saigon is “for some people, deeply problematic” and has “been seen to reinforce damaging stereotypes”. But their production, they promised, would be a “reimagining”. They had permission from the original creators to make changes, both on a line-by-line basis and a larger level, such as altering the gender or race of central characters. Fighting inequality, they argued, takes many forms: “Sometimes it’s more direct and sometimes it’s by reshaping and transforming existing structures and narratives. This project is the latter.”

Not everyone was convinced. Daniel York Loh – actor, playwright and chair of the race equality committee for Equity, the trade union for performing arts – is unequivocal about what he considers the real motivation for reviving Miss Saigon yet again: its decades-long track record of shifting tickets. “I don’t think it’s artistically bold, I’m sorry,” he told The Tribune. “I think it’s artistically timid, cowardly, opportunistic and weak.”

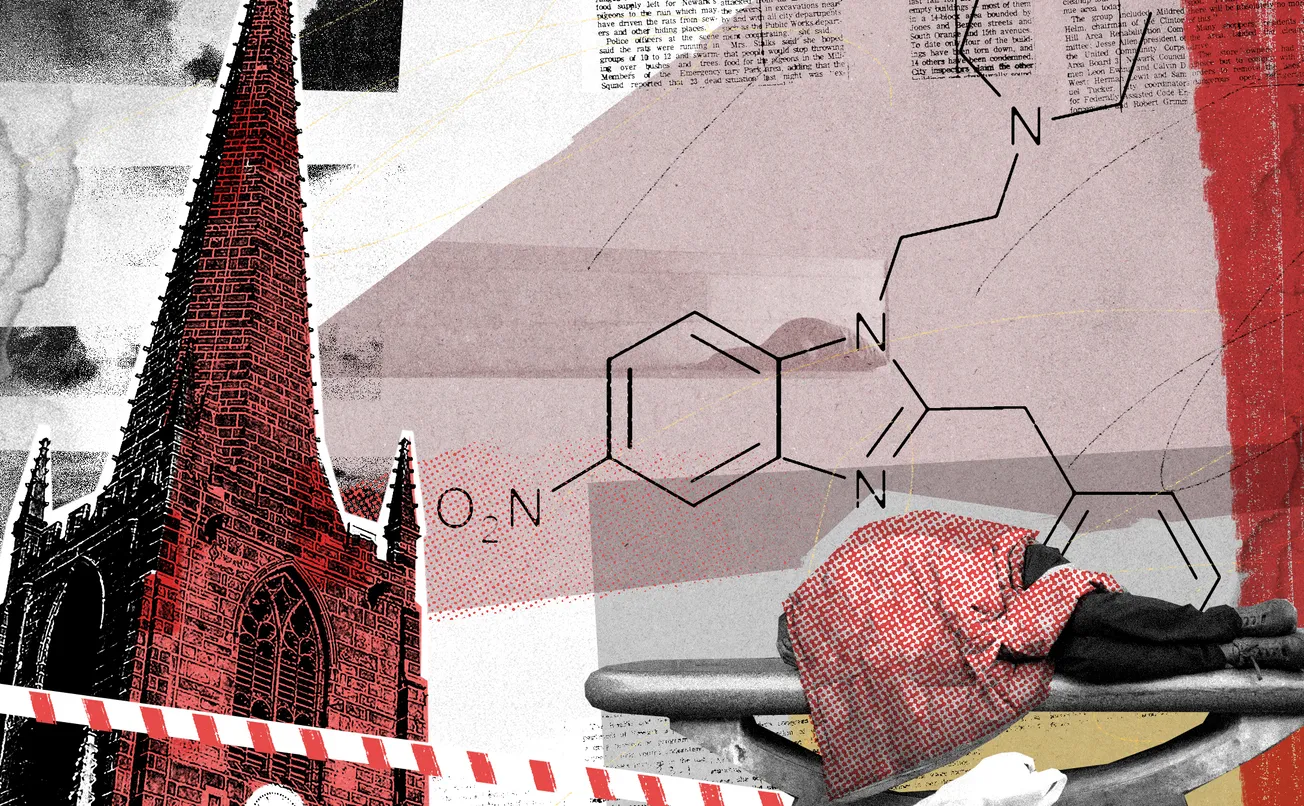

Some context, first, for those unfamiliar with the musical. Miss Saigon tells the story of a “tragic romance” between Chris, an American soldier, and Kim, a Vietnamese “bar girl” or sex worker. It is based on an Italian opera, Madame Butterfly, that tells the story of a “romance” between an American naval officer and a 15-year-old Japanese girl. In both stories, the soldier leaves and returns years later, with his American wife in tow, to discover he has a young mixed-race child. Both also end (spoiler warning!) with his former lover taking her own life.

The musical’s critics object to the plot – Daniel describes reading the summary on Wikipedia as “stomach-turning” – but certain lines in the original script added insult to injury. In the opening number “The Heat is On in Saigon”, bar girls dancing on-stage in bikinis were referred to as “these slits”. During another, a character named the Engineer mourned being “born of a race that thinks only of rice”. In the world of the musical, Vietnamese women are hyper-sexualised and desperate for the love of a “white saviour American”, as Moi puts it. Vietnamese men, she says, are meanwhile portrayed as “weak, villainous, greedy and deceptive”.

While the Tribune was unable to secure an interview with Hastie and Lau, we attended the opening night of Miss Saigon on Thursday and, as promised, they had made changes. The dancers in “The Heat is On in Saigon” are no longer bikini-clad bar girls but American soldiers – the bar girls mostly stand there and some of their outfits cover them down to mid-thigh. The Engineer is not “born of a race that thinks only of rice” but “stuck in a place where they make you plant rice”. During the interval, a woman in the seat next to me remembered seeing Miss Saigon’s West End revival in London, back in 2014, and wincing at several points. In this version, she says, it no longer feels like the women are being made into a spectacle.

The alteration that has been most lauded is the decision to make the Engineer character, a pimp, an Asian woman rather than an Asian man. This was an understandable choice. While she’s far from admirable, her naked pursuit of her own self-interest provides a contrast to the production’s other, more passive female characters. That said, making the Engineer a woman leaves Thuy, Kim’s spurned fiance and the musical’s antagonist, as the only named Vietnamese man on stage. This makes even more obvious the uncomfortable contrast between him and Chris: where the American man is loving and good-hearted, his Asian counterpart is possessive and violent.

Still, despite Miss Saigon’s controversial history, most in the theatre community insist they are reserving judgement until they’ve had a chance to see the impact of these changes for themselves. For example, Daljinder Singh – executive producer of Theatre Deli, one of only a few venues that don’t fall under the Sheffield Theatres umbrella – apologised to The Tribune for being boring but said she “can’t have an opinion either way” just yet. “It will be interesting to see whether pieces like [Miss Saigon], that are contentious and painful for a community, can in some way be redeemed.”

As far as Moi is concerned, Hastie and Lau could scrub out every single offensive phrase and it would still not be enough. “Personally, it does not strike me as radical to change one line or word[...] They have done that to make it palatable.” It concerns her that audience members unfamiliar with the Vietnam War might walk away “thinking they have learned something” and, ultimately, it is the wider East and South-East Asian community who will “suffer the consequences of the fall-out” of the stereotypes it perpetuates. The co-directors might have “declared this patriarchal ability and agency to radically change this piece of work,” she says, despite the disservice it does to Vietnamese women specifically, “but the premise is racist”.

Opposition to the premise of Miss Saigon (particularly its reduction of Asian women to damsels in distress, yearning for a Western saviour) is the central thrust of the musical’s unofficial companion piece, untitled f*ck m*ss s**gon play, currently showing in Manchester. Written by Korean-American playwright Kimber Lee, who has described it as being “born of rage”, it shows its female lead, Kim, forced to repeat a maddening loop of the events of Miss Saigon, Madame Butterfly and other stories like them. A narrator reads stage directions out loud, making explicit the unconscious stereotypes that shaped the works it parodies. For example, Clark, this story’s Chris, “exudes a very attractive manly gentleness… which we can discern in the way he regards with revulsion the oily conniving peasant men” around him.

The untitled play shows Kim struggling under the cumulative weight of decades of stereotypical stories about submissive, fetishised Asian women – “I am not lotus flower!” she screams at one point, “Or exotic innocence model minority docile!” – and fighting for agency over her own narrative. It’s not clear what new possibilities exist beyond the stories that have been told over and over before, but she’s determined to find out.

Daniel York Loh wishes Sheffield Theatres had had this attitude when they were deciding what productions to stage this summer. He’s not insistent that Miss Saigon should never be shown again, he tells me he doesn’t believe in censorship, but he finds it objectionable when Sheffield Theatres benefits from tax-payer money, both via the council and Arts Council England, which makes up around a tenth of its annual turnover. “Publicly subsidised theatre should be a place of progression, rather than regression,” he says. Instead of trying to rescue a problematic musical, Hastie and Lau could do something new. “It’s not under-produced, it’s not like they’re digging out this curio everyone is too scared to do. The people of Sheffield have had ample opportunities to see Miss Saigon.”

In his opinion, Sheffield Theatres knew “they would be able to make a big spangly production and sell lots of tickets,” because audiences in Western countries like the UK and the USA have historically loved it. “I get it, people see the catchy songs, it’s just a big spectacle to them.” But commercial shows, he argues, should be left to the commercial theatres.

A defence he’s heard East and South-East Asian performers make in favour of Miss Saigon before is that “in terms of musical theatre, there’s nothing else for them, it’s The King and I and this”. It’s unlikely that the solution to this lack of diversity will come from the commercial theatre world – developing new musicals costs a fortune, theatres will only take that risk on sure-fire hits – so institutions like Sheffield Theatres that benefit from public funding should be doing the legwork to give these actors “more choice, not less”.

Those keen to defend Sheffield Theatres, however, would respond that a small slice of public funding is not enough to exempt it from the need to make money. Pamela Johnson, a Tribune reader who worked in the arts for 35 years, argues that, “post-pandemic and in a cost-of-living crisis, theatres across the country are struggling to retain existing audiences and bring in new ones”. While she acknowledges that the original production was problematic – she “would not personally want to see a reproduction” of that show – she has faith it has been updated “creatively and empathetically”. Like Daniel, she doesn’t doubt Miss Saigon’s potential to “bring in much-needed revenue” is one of the reasons it has been staged, but she isn’t willing to condemn them for factoring that into their decision.

Judging from early signs, it appears that the musical is yet again proving to be a crowd-pleaser. Sheffield Theatres’ website says tickets are “selling fast”. A Facebook post from their official account about the production on Thursday attracted multiple comments from audience members so pleased by the previews, which began last week, that they have booked to see it again. One wrote: “We were there on Monday, it was amazing, best show ever. I'm planning a second visit soon.” After the performance on opening night, I overheard a group of friends talking about how much they had wept during the show, and where they would go next to keep drinking.

If you’ve only read the synopsis, it might be hard to imagine the musical’s appeal as a feel-good night out. However, it was written by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, the duo behind the immensely popular Les Misérables and, while they were evidently not experts on Vietnam, they knew how to write a tragic love story and show-stopper songs. In many ways, the Vietnam War in Miss Saigon is nothing more than a backdrop against which two young people fall in love, belt high notes while staring into each other’s eyes and find themselves torn apart by fate.

There’s nothing wrong with schmaltzy tear-jerker musicals – Daniel thinks Les Misérables is “one of the best musicals ever” – but the real historical conflict that Les Mis mines for pathos is the Paris Uprising of 1832, not a war within living memory. Imagine, for example, pitching a similar love story set in the midst of the Iraq War today. American soldiers in Miss Saigon singing mournfully about “all the good [they] failed to do” is a very uncomfortable understatement if you consider the historical events of the war, like the US army’s use of the chemical weapon Agent Orange and the Mỹ Lai massacre, the largest known massacre of civilians by US forces in the 20th century. The musical is more than happy to depict Vietnamese soldiers as threatening – apart from Thuy, they are a sinister mass that speaks and moves in unison, leaving Vietnamese citizens shaking in fear – but brushes over American atrocities.

The problem, of course, is that fully acknowledging the brutality of the Vietnam War would make for an abrasive viewing experience, while the commercial success of Miss Saigon relies on striking the right balance between tragedy and fun. Take the quote used to advertise the show – “Dance like it’s the last night of the world” – which suggests the concluding months of a brutal war were some kind of hedonistic final blow-out. If there were American soldiers who felt that way, their feelings were not shared by Vietnamese people. “I lost my uncle,” Moi says, “Every family lost somebody. Nobody would tell you that it was a party in any way.”

Comments

Sign in or become a Sheffield Tribune member to leave comments. To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.