By Rachel Genn

The Crucible at The Crucible is too tantalising a doubling to ignore. The vast yet intimate space of Sheffield’s renowned theatre is the perfect atmosphere for the political flickering at the heart of its namesake play by Arthur Miller, first produced on Broadway in 1953.

When it comes to producing old plays in new ways – feeding our contemporary hunger for theatrical rebirth – we understand why Simon Godwin’s Macbeth at the Depot in Liverpool put Ralph Fiennes in army combats to battle it out in a contemporary war, complete with burnt out cars and the whirr of helicopters overhead. Why, when Manchester’s Royal Exchange transported a theatrical adaptation of Great Expectations to 1905 Bengal, Pip metamorphosed into Pipli. After all, we all yearn for the new, don’t we? On entering the Crucible to see The Crucible I was almost shocked to encounter no immediate sign of reinvention, instead finding a stage set chaste as a Puritan’s prayerbook.

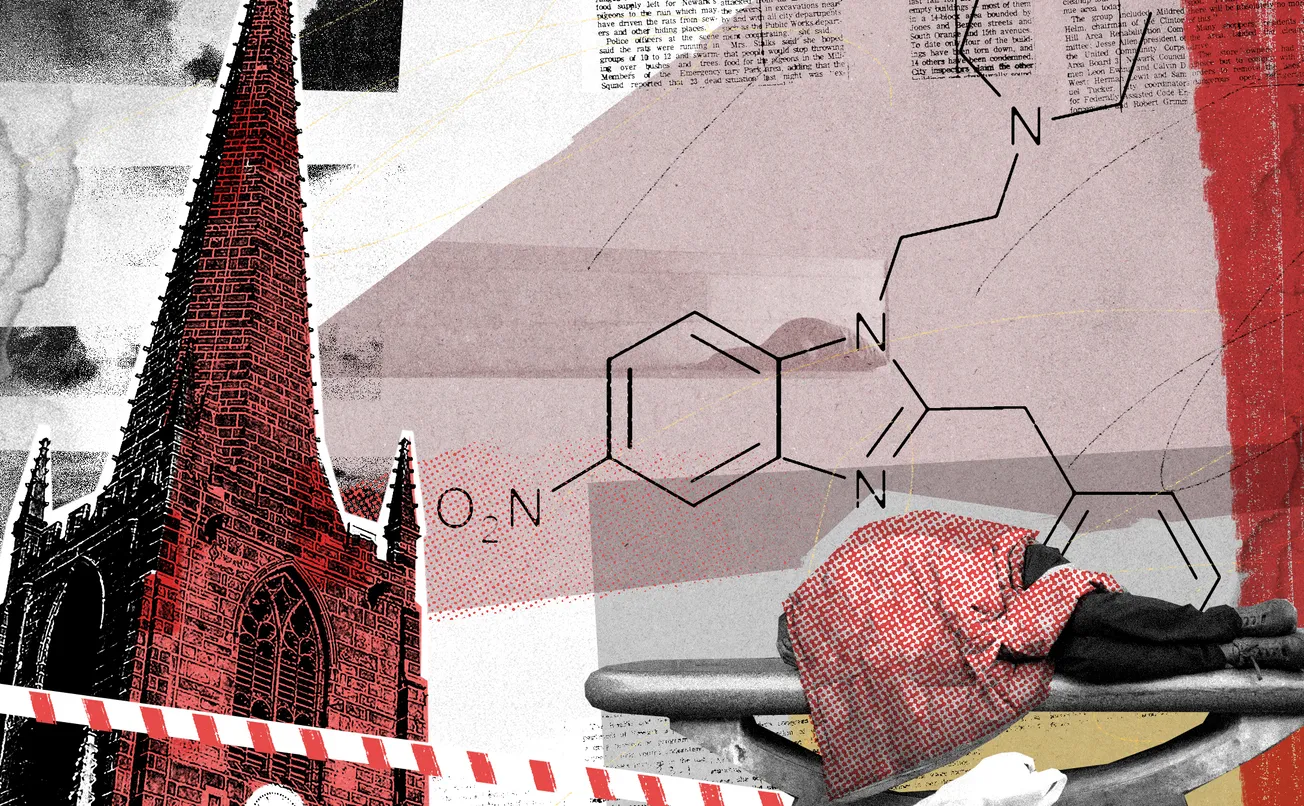

Which was a surprise, given the programme. On the cover, a preppily-dressed Rose Shalloo (playing one of the leads, Abigail Williams) perches on a gingham-covered table. All that’s missing is the apple pie. Beneath that table is a 50s-style bottle of milk smashed and spilled, with a couple more threatening to go the same way. With this visual allegory; things going sour and about to get sourer, we have the parallel between the ’50s McCarthy era paranoia of finding a Red Under the Bed and the America of the Salem Witch trials of 1692. Given the design, I’d anticipated a similarly 1950s rendition of the play. But no — the costume, the set design, most of the production indicated that this was Salem in 1692 (though there’s the occasional contemporary flourish — plastic chairs which later serve as a courtroom dock, a microphone).

For those who haven’t yet enjoyed the play, Miller’s 1953 work opens on a preacher, Reverend Samuel Parris who comes across his daughter and other girls dancing in the woods, in what he assumes is a pagan ritual. His chance encounter means the village becomes gripped by one question. Were the girls performing witchcraft? As the group’s accounts of what took place that night change and they attempt to shift blame, tension builds and the town is forced to the courtroom for a series of trials to determine who is telling the truth.

This play is about rumours and paranoia and puberty (and, of course, McCarthyism — if only via metaphor). It’s also, crucially, about sex. Sex is a driving force in the puritanical society the play depicts by the fact of its taboo. But it also fuels the play: it’s the extramarital sex the farmer John Proctor indulges in that makes his family so vulnerable and which gives this play its air of danger.

That danger is flagged from the offset by the soundtrack. The ensemble cast enter to a portentous humming, dressed with a Margaret Howell-style puritanism, we see the swish of a homespun-looking culotte or two. The cast sit observing the stage on bleachers as if at a sporting event — or is it a court gallery? One of the main objectives of the play is to present the audience with this pivotal question. Is it for sport or witchcraft that the town’s girls have escaped to the forest at midnight for dancing? An event that has led some of them to now be catatonic or unsensed?

The sound designer, Giles Thomas, heralds tension with an unnerving and unbreaking build of intonation, suggesting a shifting but never-settling blame. It carries an impending menace that the writer Ray Carver says in his 1981 essay ‘Principles of a Story’, must infuse an opening. It effectively accompanies the natural tension of the first act where calumny and personal grief entangle (like the standing mics and their leads, sometimes threatening to ensnare the actors).

That same tension is steeped through the lighting, which pulses in slow-building waves in Act One, imperceptibly, from the orange glow of portable task lamps on the ground, allowing for the gestural beckoning by the actors for a switching on of the big light to accommodate narration or asides.

The cast are talented, though they’re sometimes hard pressed to match Miller’s material. For example, John Proctor’s entrance is not as imposing as Miller’s brilliant stage directions denote, “In Proctor’s presence a fool felt his foolishness instantly…” Nevertheless, Simon Manyonda shows great emotional range as he comes to life. Similarly Rose Shalloo makes a masterful Abigail, Parris’s duplicitous niece, who potentially has more at stake than the other girls — she once had an affair with one of the men questioning her. In Lau’s The Crucible, Abigail’s girlishness and womanliness pivot around the sucking of a lollipop as she twirls between them chiming with Miller’s directions: “Our opposites are always robed in sexual sin and it is from this unconscious conviction that demonology gains both its attractive sensuality and its capacity to infuriate and frighten.”

Millicent Wong is particularly brilliantly cast as Mary Warren, the capricious confessor who flip-flops her evidence to appeal to both sides of the court, the believers and the nonbelievers in witchery, and on whose testimony most of the towns’ convictions hinge. Her comic touches are excellent (perhaps a little too far with her early flipping of the bird in introductory scenes — a measure of over-sass that momentarily draws me out of the play). The varied accents (Welsh, East End, Chinese) however do not jar, far from it, they give a refreshing gloss to the soundscape of the play.

Yes, the time and place hew to that of the script. But Lau’s confidence with the material is evident: there are contemporary inflections, moments where you see his directorial signature. The table from the programme cover punctuates the first act. Stripped of its gingham, we see it bare and supporting Betty Parris, drinking a milky potion with gusto then fallen, newly enchanted she stays, unresponsive and writhing. Her father, Reverend Parris, desperate to waken her, prays ostentatiously beside the same table. Under it soon is Tituba, Parris’ shivering Bajan slave. It becomes clearer and clearer that, despite its prominent positioning, the table is a sort of ‘secret place’ — something established early on by the intense physical entangling of two of the characters by intimacy choreographer Haruka Kuroda.

It was hard, watching the play, not to think of the history it draws from — real events just as vivid as Miller’s shining fiction. An expert on the law around ‘witch hunts’ Professor Brie Sherwin says that 1692 were dark times for the colony, the crown had recently annulled the Massachusetts’ charter which led to an unstable and unreliable legal system. In Salem of that time, the agricultural economy and modern capitalist one were pitted against each other, leading to a grinding instability that led to innocent people being pointlessly persecuted to quell that fear, many of them confessing to witchcraft to save themselves from a swift trial and almost-guaranteed execution.

Miller attests to this in his overture: “Long-held hatreds of neighbours could now be openly expressed, and vengeance taken, despite the bible’s charitable injunctions. Land-lust which had been expressed before by constant bickering over boundaries and deeds, could now be elevated to the arena of morality; one could cry witch.”

Ultimately, Miller seemed to believe the debt of gratitude lay with him rather than history. In his 1987 autobiography, Timebends: A Life, he wrote “If I hadn’t written The Crucible that period would be unregistered in our literature, on any popular level. . . So, therefore, when one says ‘It was in the air,’ I made it in the air. . . I nailed it to the historical wall.” A rather self-referential, almost Reverend Parris-like admission.

Throughout, the lighting and sound arrangements keep the heat stoked. We can almost smell the cost of Proctor’s lust, the pyres smoking already for the accused villagers. Lighting designer Jess Bernberg’s intentions for this production are hiding in plain sight as Abigail and Betty are lit, gleefully chanting names plucked from the air and the girls together are spotlit at the end of their dance and incantation with Tituba, inserted midway through the play.

Descending strip lights for the court scene and a hanging boxed array emblazoned CRUCIBLE that sparks and glows to summon the devil, reveals jail bars or crackles to quicken the firecracker contagion of accusation.The mics are used innovatively, pulling of the plugs cleverly signifying an intolerance for and an unwillingness to lend the character’s voice to the way things seems to be going.

Professor Sherwin notes that today, those who claim to be the subjects of witch hunts are often powerful men. There’s an irony at play here when you think of how the 17th century witch hunts generally targeted and persecuted strong-willed or wayward women, social outcasts. Sherwin goes on to note that Trump has deployed the term hundreds of times to describe how unfairly he’s been treated. Perhaps the resulting peril of repeating a phrase like “witch hunt” is that one day, those doing the hunting may be inspired to give it a new meaning, a new narrative, that defends those with the power.

Lau’s The Crucible makes a compelling case for traditionalism in theatre. It felt like that hackneyed Flaubert quote, applied to the stage in lieu of your daily routine: “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” By ducking the responsibility of transporting The Crucible to a different time, a different location, a different galaxy, Lau seems free to experiment with the details that bring a production to life: the lighting, the soundtrack, the set. His production is playful, contemporary and operatic. For a play so frequently in production, Lau’s allegiance to the traditional setting takes real courage. I can’t wait to see what he does next.

Comments

Sign in or become a Sheffield Tribune member to leave comments. To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.