“Go and get a job — cunt.”

I didn't think it would be difficult to find what I was looking for, and I was right. As I emerge from Sheffield train station into Sheaf Square, I see them straight away. Two women are conducting a very loud argument outside near the snaking Cutting Edge water feature, their rowdy tête-à-tête attracting the attention of a growing number of commuters.

One is sitting down on the floor with an obedient dog, covered in a fleece blanket. The other stands, animatedly walking this way and that around the seated woman. I try as best I can to tune in to their conversation, but it’s an argument over money which I can’t fully follow. “All I know is whatever money you owe him, you owe me,” the standing woman shouts. Dressed in a camouflage army coat, she’s carrying two Sports Direct bags and a canvas rucksack. On her head she wears a beanie hat from which two large gold hoop earrings protrude.

The argument gets worse. The woman on the floor suggests that if the other needs money, she should become a sex worker. “If I did I’d get more than you fucking would,” she shoots back. I obviously don’t know the rights and wrongs of the argument, but it’s difficult not to feel sorry for the woman on the floor. Covered up in a dirty pink blanket, her hair tied up in a scraggly ponytail, she looks desperate. Like this argument is the last thing she needed.

But if Sheffield Council gets its way, a proposed new law could see her and many others like her moved on for begging, loitering or being intoxicated in public. A consultation is currently underway on a public space protection order (PSPO) covering the whole of the city centre. This new law would see council staff and police given new powers to stop people drinking alcohol, taking drugs, begging, loitering, and urinating or defecating in the street. If they refuse they could be fined up to £100.

The council say they want to bring in the law to keep businesses, residents and workers safe and free from harm, harassment, alarm, distress, nuisance and annoyance. They point to the fact that Sheffield is the only major city which doesn’t currently have one and that persistent anti-social behaviour, particularly along a corridor from Fitzalan Square to West Street, is ruining many people’s experience of the city centre. However, some critics argue that rather than solving the problem, the PSPO could simply move it elsewhere.

As the woman’s antagonist finally walks away, she relights a half-smoked cigarette. Walking over, I ask her if she’s ok. It turns out she’s called Colleen and she’s just turned 50 this year (“You shouldn’t ask a lady her age,” she scolds me). Her dog, an American Bulldog called Skye, sits patiently by her side, part-covered by the blanket. Colleen has been on the street for 49 months, but this is all about to change; the council have finally found her a place to stay.

The public space protection order is news to Colleen, but when I tell her about it, she’s worried. She asks what vulnerable people in the city centre meant to do without money or somewhere to go. The Archer Project and Ben’s Centre — longstanding services for homeless and vulnerable people in Sheffield — both close in the early afternoon. This means that from the time these services shut until a soup kitchen opens on King Street at 8pm, the homeless people, rough sleepers and beggars who live in our city centre are left completely to their own devices. “There is no support in the afternoons at all,” she says.

I think of the incident I just witnessed. On the one hand, why should commuters, shoppers and other city centre users have to be subjected to foul-mouthed rows just walking past the train station? A common complaint that people make online is that they’re put off coming to the city centre by endemic anti-social behaviour. When The Tribune broke the news that a PSPO was being considered last year, Sheffield BID, an organisation which represents city centre businesses, praised the council on Twitter for its “important” work on the PSPO. “Whilst recognising the challenges, this is an important step for many city centre businesses,” they added.

On the other, is it really going to do any good? Taking someone’s alcohol, drugs or means of obtaining money away might give the appearance of solving a problem, but it’s likely to create others down the line. Wouldn’t it be best to address the root causes of the problem instead of the symptoms? At the communities, parks and leisure committee meeting, Green councillors voiced their opposition to the PSPO. “The Public Sector Protection Order, as described in the consultation document, would mean that someone sitting on the floor quietly with a hat could be regarded as someone who is likely to cause harassment, nuisance or annoyance,” said Gleadless Valley councillor Marianne Elliott. “Is it really sensible to issue a £100 Penalty Charge Notice to someone who is begging?”

Outside the Salvation Army’s “Lifehouse” on Charter Row, I speak to Keith, 57, who is originally from Totley. Disabled and using a crutch, he wears a plain black hoodie and has tattoos all over his body, including his shaven head. On its website, Lifehouse says it provides 55 beds of supported accommodation for single males aged 18+ who are experiencing homelessness. Keith has been there for three months since he was kicked out of his previous home by his ex-partner.

Keith is currently living on ESA (Employment and Support Allowance) and is waiting for his “priority”, meaning that because of his disability he will be able to get a home quicker than otherwise. Still, he has been told that he could well be there for several years until a suitable property is found. He tells me he has begged in the past but doesn't anymore. Most of the other residents at Lifehouse do though, he adds.

“Begging is how people here get their money,” he says when I tell him about the PSPO (again, like Colleen, he’s completely unaware what it is). “There’s a lot of people who are going to be upset about it.” And if they can’t beg, I ask? “They’re going to be robbing shops.” Keith also tells me that the PSPO could lead to begging and anti-social behaviour simply being moved elsewhere. While most of it goes on at well-known places like Fargate and High Street, some travel out to places like Hillsborough or Ecclesall Road. “It could force more people out into the suburbs,” he says.

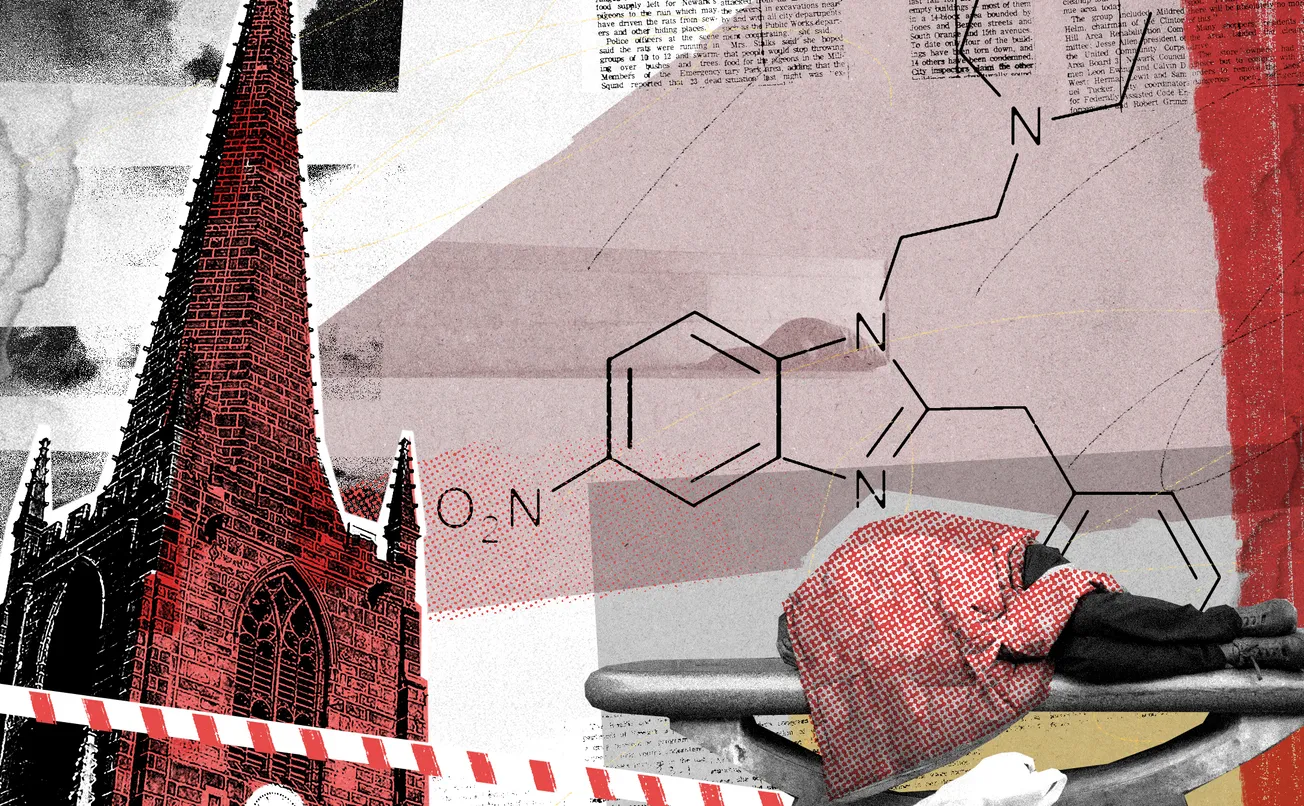

I’ve skirted around the main areas I know, but eventually I have to bite the bullet. If there is a “ground zero” of anti-social behaviour in Sheffield city centre, it’s the area of High Street around the Cathedral. When I first started working at The Star in 2018, walking from my flat at Park Hill to the office on Pinfold Street was a distressing experience. 2017 and 2018 was when the Spice epidemic really took off, and most mornings the pavements were scattered with people who were completely paralytic. Things have got a little better since then, but the area can still be an unpleasant place to walk past. You regularly see people in distressing states, drinking and taking drugs and arguing with each other. It’s not exactly conducive to the continental café culture the council supposedly wants to create in the area.

Outside McDonald’s I get speaking to Paul, who is sitting on the floor begging. He’s dressed in black jogging bottoms, black trainers and a long black coat. But it’s been raining for an hour now and he’s soaked to the skin. He tells me he has a place to live in Pitsmoor but this is the only way he can make money. As a result he often stays in the city centre overnight. “I need to do this to live,” he tells me. The PSPO could mean him returning to shoplifting and going back to prison, having only been released five months ago. As we’re sat chatting, someone drops a £10 note into his hand. “You must have brought me good luck,” he says as he offers a fist bump. The money, he says, will buy him a decent hot meal in the morning.

On Fargate, I’m taking a picture of a sign asking people not to sleep in a doorway when I bump into Arbourthorne Councillor Ben Miskell. He’s chair of the transport, regeneration and climate policy committee, meaning the PSPO is not his brief. However, he is happy to say it is something he supports. “We need to make the city centre an attractive place that people want to visit,” he says. “My mum lives in Oughtibridge and she wouldn’t come to the city centre. She certainly wouldn’t come to this bit.”

Miskell lives in the city centre himself, and says it would be a mistake to think of the PSPO as just being about begging. He says it’s also about giving the council powers to disperse people from known trouble spots like Carver Street, where violence often flares on Friday and Saturday nights. 20,000 extra homes will be built in the city centre over the next 15 years, which will mean that we have to start thinking of the area more as a neighbourhood than we have before. “I think we should have a PSPO and I think most people in my block think so too,” he says.

If the PSPO does come in, the people who will have to enforce it are the police and the City Centre Ambassadors. The consultation document says enforcement will “enhance and not work against” current harm reduction initiatives and will be used to identify and address the support needs of people breaching the PSPO. It adds that fixed penalty notices will be “used where appropriate” but will not be the default response. A helpful City Centre Ambassador tells me much of what the PSPO covers is already illegal, but that the order would give them new powers, meaning they could issue civil penalties themselves. If this is refused, they can then get police involved. “The idea is that it is meant to be the council and police working together to enforce it," he tells me. Is that something the City Centre Ambassadors support? “No comment,” he says.

Daryl Bishop is the CEO of Ben’s Centre on Wilkinson Street, an organisation which works with homeless and vulnerable people in Sheffield. He tells me that while he understands the pressure from the retail community for this power to be brought in, he’s worried that it will be little more than a sticking plaster and won’t address the true causes of the problem. “The people out there are doing what they're doing because they're desperate and broken and they need help, not just moving along to somewhere else,” he says.

Bishop says that a lot of the language in the draft order mentions the use of clothing like hats, or acting in a way that would cause annoyance. “To me that’s just passive aggressive against our client group,” he argues. “It’s not worded like this but it’s very much like saying: ‘we don’t want you riff raff in our town centre’.” He says that if extra police are going to be deployed to say ‘you can't drink that cider there’, that could damage the already poor relationships between their clients and the police. And he adds that if people get their drinks either confiscated or poured away, they are likely to either beg to get another one or steal it.

The draft PSPO documents say that efforts will be made to encourage vulnerable people to access support to change their behaviour or address unmet needs. However, Bishop tells me that all the services in the city are really struggling just to keep their heads above water at the moment, including the Archer Project which has recently had to reduce its hours because of skyrocketing costs. If the PSPO was used as a last resort after all else had failed then it could succeed, but there just isn’t enough support out there to meet the needs of everyone who will be affected. “I think if used right this could help funnel people into the right services,” he says. “But I don't think anyone's got enough money to make this work well.”

Everyone accepts the need for change. But is the PSPO coming at the problem from the wrong angle? Is it trying to solve problems that need systematic change rather than new enforcement powers? Countries with café cultures often have stronger social security nets, more free stuff to do, and lower cost housing. Unsurprisingly, there is less homelessness. Simply making begging illegal doesn't mean that you're eradicating homelessness — it just makes it harder for the most vulnerable people in society to survive.

In the late 2000s, the number of people sleeping on the streets in the UK were numbered in the hundreds. Homelessness, to all intents and purposes, had been eradicated. But almost 14 years of funding cuts to local government have reversed what progress had been made. Official statistics show that across the UK, there were two-and-a-half times as many rough sleepers in 2019 than there were in 2010 — an increase of some 150%. It’s understandable that in a cost of living crisis, when businesses are fighting for survival, many will see anti-social behaviour as one more problem they don’t need. But unless there is enough support in place, the PSPO won’t solve the problems — it will just move them elsewhere.

What do you think of the PSPO? Is it a reasonable response to a growing problem, or yet another way of punishing some of the most vulnerable people in our city? As always, paying members can let us know what they think in the comments section.

Comments

Sign in or become a Sheffield Tribune member to leave comments. To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.