A pal suggested that if I was writing about Occasions nightclub (circa 1988-92) I might ask mates for their late eighties photos but I am not mad keen on reality. I like not knowing whether I dreamt something or not. For example, I don’t know whether the fire-damaged quality of my memory of this tiny club is something built into the memories themselves, or the result of some online news story that I stumbled upon previously about Occasions after a fire. Whatever the reason, my degraded recall gives me licence to remain agile around truth.

I was always going to write something about the scale of this club, tucked away in the top floor of what used to be a restaurant in Charter Square. I couldn’t quite get to what right-sized meant but I couldn’t shake the aptness of it as a description for Occasions. Then, alarmingly — as I haven’t known the person for long— I shouted Yes! when a new friend confessed that being in church they felt right-sized.

With this foothold, I began to pull together the interior of Occasions for inspection, discovering that my memory is losing elasticity and that perhaps the first elements to become unreliable are dimensions. I imagine this is common since it is a truism that school halls, previously cavernous with foreboding, lose their looming dread once revisited as an adult. It’s unsettling to understand that there’s a choice in what we remember.

If I am honest, lately, I have discovered that what I cling to as facts are often not, but rather are solid, durable unrealities that I find preferable to uncertainty. Pressing on, I apply to my memory these short miraculous sentences from Unquiet Landscape by Christopher Neve, “The picture is its own country,” and “A state of mind becomes a place.” What happened in Occasions transcended personal experience and instead of me was about us, there, then.

You entered Occasions as a wave, distinct and thinking yourself worthy of attention. Whether it was the heat or the oxblood walls, you very soon melted into the swell and became indistinguishable. A blessing, because on the tiny signature dance floor, enemies were as close as friends. There was something distinctly burgundy about the whole affair in this first-floor club beside a car park, just up from Sheffield’s mid-sized BT headquarters. For four hours on Saturday night, the world we came from dissolved in a deep red surge of togetherness. None of us had anything but what we wore. No-one we knew was rich, though a handful of guys who worked in Next had found the fashions of Sheffield to be prohibitive, and had upped sticks to LA.

We, who made up the core crowd, had split off from larger clubs in Manchester and Notts and in pledging allegiance to this unheard-of and diminutive boîte du Nord had somehow strengthened our association so that on a weekend night, paranoia grudgingly gave way to awe.

My connection to the club began before it existed. Around 1986, I sold a 12-inch, white label, house import to DJ Winston Hazel from behind the counter at Aldine Court and from that flimsy transaction, I felt he owed some of his on-going success to me. This fantasy extended to a sense of ownership of Occasions, where he and Parrot (Richard Barratt) regularly DJ’d in the late 80s and early 90s. I had taken this paltry gesture and made it into a secret handshake gaining me entry into a club that was to seal my identity and, however unwarranted, galvanise my vibe as a late teen and early twenty something. In this club, you were always arriving. It was this sense of impending climax that Occasions, a velvet crucible of house and techno, did best.

Once inside, you could lose your boundaries and merge with your fellow man through music and claggy speed; powering through cans of Red Stripe so capacious that the bottom swallows were always warm no matter how thirsty you had been. Ill-advisedly, I once tried to rag a belcher off my fellow man and was throttled by a bouncer, who then smoothly dispatched me, stiff-necked and swinging like an not-quite-toppled pin in a bowling alley, down the angled stairs and out onto the street. The stairs leading up to the entrance of the club doubled back on themselves and because of this arrangement, queuing for this club never felt oppressive. It became instead, a thrilling opportunity to ogle and identify what others were wearing without being detected. At least, I think that’s how it was.

The scale of the place, like a miniaturist portrait, managed to be both endearing and enchanting. It was absolutely itself, not merely a smaller version of the brasher, louder-shouting Northern clubs of that time. Objectively, Occasions was a sweaty, awkwardly arranged collection of ill-used space arranged into zones. Barely a strip of walkway was allocated to the bar but, in my memory at least, acres were devoted to the toilets (my brother-in-law had a tache and people would shout copper whenever he entered). The bathroom floors were perpetually sodden, and could ruin a wrap of wizz.

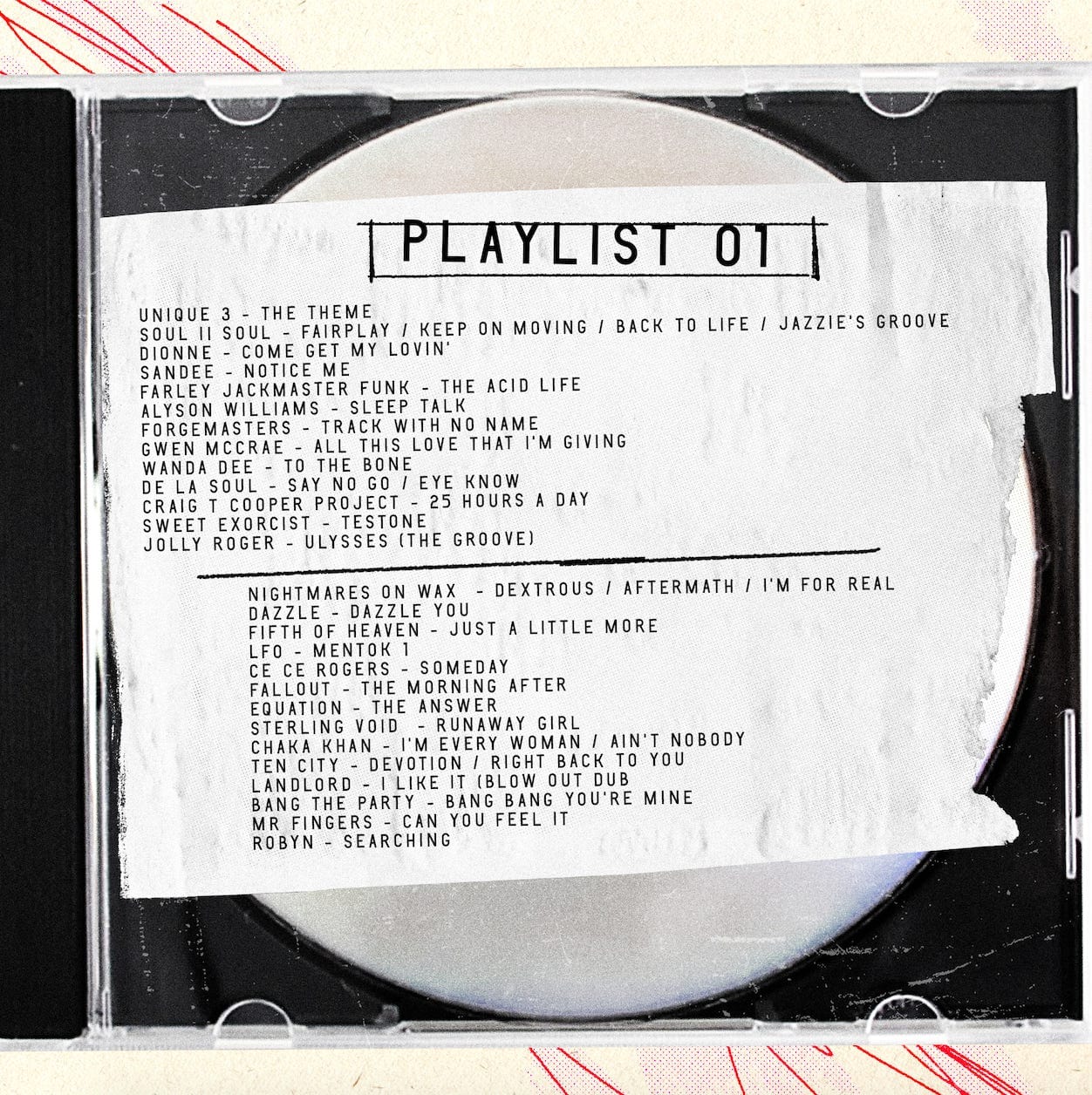

To test whether you’ve been tripping or not, there’s a section of the Mystical Experience Questionnaire that tries to winkle out a “sense of sacredness.” I won’t say high priests, but Winston and Parrot, as far as resident DJs go, enhanced our sense of belonging through their skills and in pledging our entry fee, we were giving them permission to deliver us. With records from Nightmares on Wax like Dextrous and LFO’s Mentok 1, we found what we were looking for: a way to make threatening noise joyous. The Superman Club on Saturday night was at the very least, a devotional safe space for those up for a stint at aggro-love.

You might find it a stretch to say the atmosphere in Occasions edged into mystical, but to me, the jumble of quads and perspectives meant there was a sense of the relational aesthetics embodied in The Ark of the Covenant or diagrams I’ve seen of a Freemasons’ lodge. A sense augmented by the rustic garb that was leaking into clubs at the time. My gunmetal grey hippy-top for instance, contrasting with the vivid primitive print Gotcha trousers, procured at great expense from Boatworld on London Road. Mirrors were being sewn onto hippy bags around about now. That kind of trifle.

In Occasions, we couldn’t help but unite, the size meant we couldn’t escape each other and this helped us bring on the insight that ‘all is one.’ This club was not a showcase for the earnest jazz-dancing that demanded a certain circumference of sprung-floor to perform, so coveted at Jive Turkey at The City Hall (where Occasions— previously Mona Lisa’s—had migrated from). With barely room to dance, we were more than a close-knit movement. That its life as a club-nite was barely more than a few yards of stapled together high-octane encounters, taken up on thermals of Yorkshire-bred techno, made it more valuable to us.

I was put out to be told that the dancefloor was invisible from the DJ booth since I had captured a golden experience, of being crushed against the lamplit glow of the perspex booth, our chubby faces studding the glass and safely out of earshot, predicting what Winston and Parrot had for us next (one of us perhaps still radiating a curatorial pride over Winni’s record choice). No-one was fool enough to ever request what they really wanted to hear, nothing as gauche as that, but once a record we all secretly wanted was played, I can vouch for a rush that could be described as a sense of “profound humility before the majesty of what was felt to be sacred or holy.”

There’s a particular strand of house music that spins into play when I look back. If I had to define it, I’d call it Voodoo House. Way down in the trammels of a set, things would get dark and serious, channelling the vibe from blessed to ominous, the crowd lifting to lyrics like Mrs. X your son is dead. Lines of tracks became oracular even— I can still hear the plaintive stretch in the repetition of Give me a child/a child/of an impressionable age, and then the drop into downright sacrificial with Bang Bang, come here little girl. Beneath all this was the question: what price would we pay for our weekend deliverance? Not one of us could hear it above the noise. We were elated that our DJs cared enough to teach us what we might not have liked without them.

What I have left of Occasions is what we had back then rinsed through what’s happened since. Looking back at his formative years, Nabokov saw the awakening of consciousness as a series of spaced flashes, with the intervals between them gradually diminishing until bright blocks of perception are formed, affording memory a slippery hold. But I have enough left of this ruined heaven to appreciate that downplayed yearning for connection, through which comes unbidden a pulsing silhouette, black, white then Prussian blue. It’s a picture made of what was once there, a cyanotype fixed only by a stark slash of strobe, and I can just make out two straight men— their not-quite-thereness framed off then on in light —and they are kissing each other like their lives depended on it.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.