On 18 June 1984, as day broke over Sheffield, the birds were tweeting and blue skies ensconced the city. As picketing miners made their way to the Orgreave coking plant, they began to unbutton or remove shirts as the sweltering temperatures continued to rise. Villagers greeted them with orange squash and ice to help quench their thirst. Unusually, so did the police, who, rather than stopping them miles from the site, welcomed them onto it. Within a few hours, the mood would change. What had started as a glorious technicolour summer morning would soon turn a darker shade, thanks to the blood that poured from the wounds of countless men. It would be one of the most violent incidents in British industrial history.

40 years on, the events of that day still linger. On a recent Sunday morning, the sounds of a brass band echoed out as people flocked into the Crucible theatre to watch the world premiere of Strike: An Uncivil War. The film depicts in great detail what took place on the day dubbed ‘The Battle of Orgreave’. By the time the credits rolled, the entire room was on its feet, with cheers erupting and tears running down the faces of burly men. When I meet the film’s director Daniel Gordon the next day, the news that it has won the Sheffield Doc/Fest Audience Award has just landed. “I'm buzzing from it,” he says enthusiastically. “Not so much for me, but because this is going to mean so much to the families [of miners].”

In March 1984, the National Coal Board announced that the Cortonwood colliery near Rotherham was to be closed. This action had followed years of increasing pit closures and so, fearing more targeted closures, the National Union of Mineworkers, led by Arthur Scargill, called for industrial action and national strikes began in order to save jobs. Around three-quarters of the country's 187,000 miners participated in these strikes, which lasted almost a year.

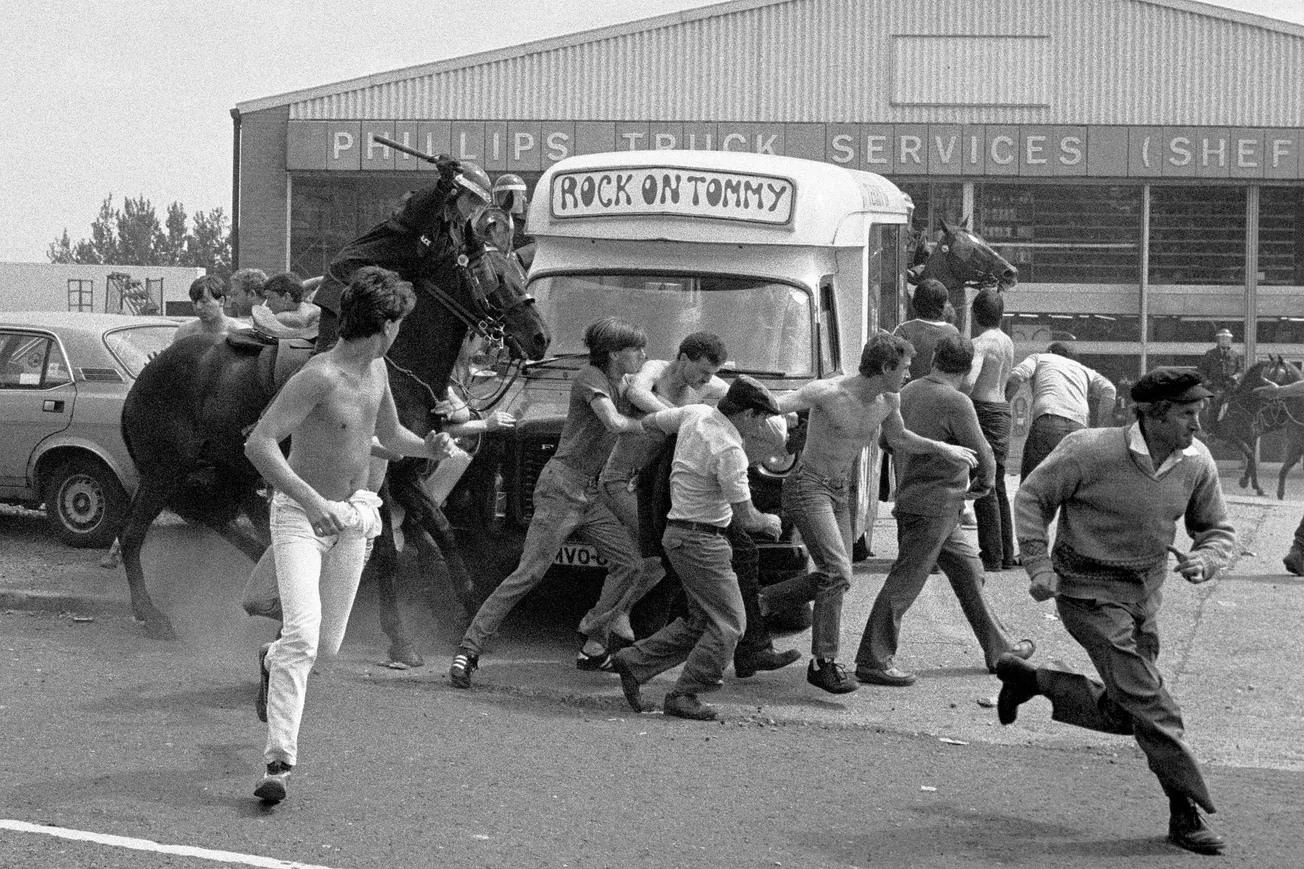

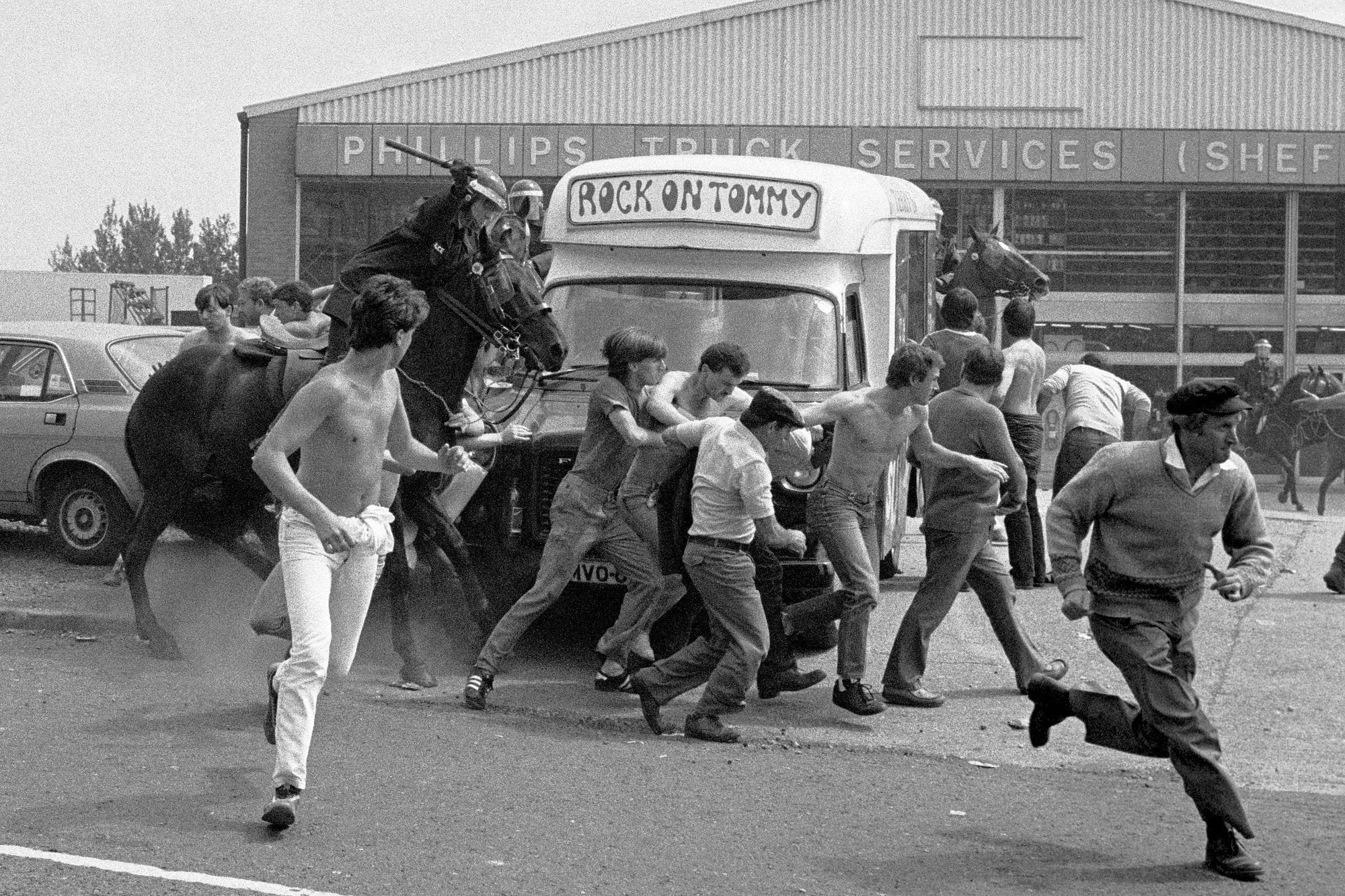

104 days into the strike came Orgreave. Five thousand miners picketed the site in an attempt to block coke — a byproduct of coal when heated, and used to make steel — coming from the plant. They were met with a huge police presence, who had been freshly emboldened by the 1983 Public Order Manual. This document, which the Home Office had created secretly and signed off undemocratically and without public consultation, gave police greater powers for dispersing crowds. They could use batons on people simply for being present, as well as police horses to break up groups, which were used to charge at the miners. It was described as paramilitary in its approach, with the historian Tristram Hunt later describing it as “a brutal example of legalised state violence.”

Close to one hundred arrests were made, with many of those charged for riot, which at the time carried a life sentence. A subsequent court case collapsed in 1985, as police evidence was deemed unreliable and falsified. Charges were dropped; some miners received compensation, but no officer was charged or disciplined for their actions.

Daniel Gordon already knows about a decades-long pursuit for truth and justice — the 52-year-old Sheffield-based filmmaker previously made the Emmy-nominated 2014 documentary on the Hillsborough disaster. It was while making that film that the genesis of his latest came to mind. “It all starts with Orgreave,” he says. “One leads to another. Without Orgreave, there is no Hillsborough. And there certainly isn't a Hillsborough with that depth of cover-up.”

Strike has been a passion project for Gordon. “Every single person who's worked on this film has effectively given their time for free,” he says. “Sometimes the crew have just worked for their petrol money and hotel for wherever we've gone to do the interviews. But everyone was the same in their thinking: we've got to make the film, we've got to tell the story, and we've got to give them a voice.”

There’s perhaps also a feeling that some of the media portrayal of Orgreave over the years needs to be corrected. The BBC’s initial coverage of the event suggested the miners had instigated violence rather than the police, and was seen as so misleading that the corporation would make a public apology years later. And during one recent Q&A following a screening of Strike, a miner publicly criticised the “rubbish” three-part Channel 4 documentary released earlier this year, Miners’ Strike 1984: The Battle for Britain, because it incorrectly used footage from another day to depict the events of Orgreave. “It feels like it’s the first time that the miners’ strike and Orgreave has a definitive film,” says Gordon. “One that forensically pieces together the day.”

It’s an incredibly powerful film. Even the trailer is a struggle to get through, as a series of clearly broken men recount a day that they’ve never been able to get over. “I've deliberately tried not to make a campaigning film,” says Gordon. “I don't think I've approached it as a political film. I see it as about community. But I want you to feel that emotion and that wrench and that anger as you leave the cinema, saying: ‘there should be an inquiry about this’.”

For the last decade, there has been demand for such a thing via the Orgreave Truth and Justice campaign. In 2015, the campaign group provided a lengthy legal submission to then-Home Secretary Theresa May, calling on her to set up an independent public inquiry into the policing on that day. In 2016, with Amber Rudd now Home Secretary, it was rejected on the grounds that there had been no deaths nor wrongful convictions. Months earlier, previously censored documents had revealed further links between the cover-ups at Hillsborough and Orgreave, yet Rudd refused to explore them any further, stating: “That is not a conclusion which I believe can be reached with any certainty.”

Gordon feels the false statements given by police at Orgreave laid the groundwork, and the governmental relations, for Hillsborough to be dealt with in a similar way. “At Orgreave, they’ve made up a statement and pretended another officer had witnessed it,” he says. “It's fitting someone up. It's the most blatant fit-up. It goes to court, the case collapses, but there's no consequences. What does that tell the police? You can get away with it. And it's the same senior officers that are in charge during Hillsborough. They've done the same alteration of statements in both cases.”

Gordon’s claim that he’s not made a campaigning film doesn’t entirely stand up — it’s clear he has an impassioned and unapologetic agenda. However, he’s also right in that the film doesn’t explicitly scream it. It doesn’t need to. Instead, it meticulously presents footage, evidence and emotional testimony that makes such an outcome feel undeniable. There are police officers on screen admitting to statement tampering, an ex-BBC journalist expressing regret that they fell for the “propaganda” being pushed by the police at the time, and numerous miners who recount the life-shattering impact of the police violence that day.

The film leans heavily into the miners’ words to hit its point home, but by being balanced with clear proof of wrongdoing and offering a broad range of perspectives — including miners who gave up on the strike and returned to work — it doesn’t veer into heavy-handed or emotionally manipulative territory. A successful film about Orgreave should instil anger, and this does. But the anger that one may feel from watching the film does not come from calculating narrative techniques intended to elicit such responses, but from the sheer overwhelming obviousness of the injustice.

For those who know the miners’ strike inside out, it may not prove to be all that revelatory with much of what is presented evidence-wise already being on public record. However, Gordon feels that documentaries can do a different job. “Documentaries can tackle miscarriages of justice in a way that books and newspaper reports simply can’t,” he says. “This happened for my Hillsborough documentary too. There was very little in that film that hadn’t been said, reported on, or written about at some point over the previous 27 years. But it managed to put everything into one place, and by showing it visually, everyone can see for themselves rather than trying to imagine scenarios. As a result, the impact was so much deeper.”

Part of the reason the film is filled with so many tears is because it became clear while making it that a lot of these men had never really spoken about what had happened on that day. When horses charged, and freshly issued riot gear and batons were put to full use, many men had to run over live railway tracks or hide in strangers’ gardens to escape. Some were scooped up by snatch squads and were arrested and charged with riot, fearing a life sentence in prison. “The heart of the story is that these people are effectively baring their soul,” says Gordon. “You've got these working class heroes, big, strong men, crying; and clearly crying because they've not processed what's happened over the last 40 years. And they've never done that until the day they sat down with me.”

One such contributor is Ian Mitchell, who I meet after a second screening of the film. “It was very, very emotional,” he says. “But I was so relieved when I watched it. We've been treated with a lot of respect and the film has proven absolutely conclusively that they [the police] started the fight.” Mitchell was 26 and married with a three-year-old when he went on strike. It’s been difficult for him to revisit what happened on that day. “It was absolutely terrifying,” he reflects. “It's trauma-inducing, watching it all again, but it's important.”

It was a period in Mitchell’s life that he looks back on with both pain and pride. “It was a strain,” he says. “Me and my wife split up because of the strike. I would be followed by a vanload of cops giving me abuse and threatening me while I've got my daughter in the pram. I can never forgive that. But people ask me if I would do it again. Yes, I would. In a heartbeat.”

The wider impact was also significant. “You kill a pit and you kill a community,” says Mitchell. “And that's exactly what happened. Some of these places became ghost towns. They just wanted to smash us by any means necessary and provide nothing in its place. Just leave us to rot. Work like that provided a social glue that held everything together. And that's where you drew your dignity from, you felt proud of what you did. You had a community.”

The film examines what happened in the lead-up to that day, and positions that the pit closures were a premeditated and calculated revenge move, intended to destroy the unions, for the successful 1972 and ’74 strikes. It also forensically details what happened on that day, almost hour-by-hour, as well as the mass framing of innocent people that followed and the subsequent court case that collapsed after it emerged officers had lied on their arrest statements.

But in telling all of this, one of the greatest takeaways from the film is the fallout and the long-lasting impacts it had. “We're all suffering what we call today ‘post-traumatic stress’,” says Mitchell. “After the strike, a lot of people suffered from poor mental health, but people didn't like to admit that or speak about it. And people have paid a terrible price. I know people who took their own lives. I myself suffered from depression.”

“You're dealing with really traumatised people,” says Gordon. “When you're in a community, and you're all on strike, you're all in it together, you're all there. When you all lose together, you're all there. When your community gets battered, you're all there. But it's really when you sit back and think, ‘fucking hell, what happened to us?’ And you know you've been done by your own government. I wanted to show this is what they did to people, by divide-and-conquer methods and brutally making this an unconditional surrender war.”

This sense of community runs in Gordon’s own family, and was in his mind when making the film. “In 1947 there was a really harsh winter,” he recalls. “And my mum's mum, who was an immigrant, had only just moved here, and her husband was still away in the army. One day in the Co-op she happened to say in passing that she was going to run out of coal that night and it was freezing. The following morning her coalhouse was full with a year’s supply of coal. She never found out who did it, and no one ever told her. That's why I want to tell this story — for them.”

In the film, a group of miners all return to the Orgreave site. Mitchell, however, did not participate. “After the strike, I used to go back to Orgreave a lot and just sit and wonder what could have been and what had happened,” he says. “But I can't go back there now. I don’t want to. You never really get over it or deal with it because it was such a trauma. I mean, it wasn’t just that day, it was a whole year. The poverty we were suffering, and then just what they were doing to us… but we fought like bloody tigers.”

When the strike began, there were 170 working pits in Britain. Within the ensuing decade, just 15 remained. “Basically, the government didn't agree with the way that these people thought, therefore they destroyed their community,” reflects Gordon. “It wasn't like, ‘well it's no longer economical for us to do this but we're going to retrain you.’ They just didn't do that. And it's really devastating. The winner literally took everything.”

Several of the miners in the film reflect on how villages that were once centred around employment in the mines became flooded with drugs and despair. “You go around these places and now they are shitholes, and they weren't shitholes before,” says Gordon. “You can't be romantic about coal mining. It's a really dangerous job, and a lot of these people are ill — there's a guy in the film who dies who you think is 90, but he's 70 — but these were places filled with proud, patriotic people.”

However, 40 years on, despite the numerous articles, the books, the conclusive proof of excessive violence, the police cover-ups, and all the evidence that shows Orgreave as the travesty that it was, there is still nothing in the way of justice for those affected or consequences for those who inflicted it. But there is a feeling that this may finally change. The new Labour manifesto explicitly states that they will order an investigation, and both Gordon and Mitchell are hopeful the documentary could prove vital if that goes ahead. “I hope what the film does is show that there's enough there to have a proper full inquiry and holding to account of what happened,” says Gordon. “People never get over this and they shouldn't be expected to. It's a deep, deep scar. But the truth being out is actually some level of comfort for people. And just to be believed is the big thing. It’s so important for these people.”

As someone who has followed the Hillsborough campaign for so much of his life, does Gordon have faith that such a thing will come good in the end? “I have very little faith in the government and the system,” he says. “History has proved time and time again that I am right to be wary. But also, history has given us the one shining example of the Hillsborough Independent Panel Report. Now if that could be repeated for Orgreave and the miners’ strike then I would be far more confident that we could get to the truth.”

It’s something that Mitchell desperately wants to see happen. “There's so many guys who have died now,” he says. “People who were involved in that strike, and were as passionate as me about it, and who wanted to see some kind of justice. And they've gone. I hope I don't. I'm 66 now and I just hope I get to see it in my lifetime.”

Strike: An Uncivil War is screening in cinemas across the UK now.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.