Good afternoon, readers — and welcome to today’s edition of The Tribune.

With £900 a month, you could rent a pretty swanky place in Sheffield. Right now, there’s an entire one-bedroom penthouse flat for that sum within spitting distance of Kelham Island. Or if you were happy to share — with a “multidisciplinary creative director” who notes he’s often away travelling for weeks at a time — you could nab a “king size” bedroom in the regenerated Park Hill for £100 under your budget.

Where you’d be unlikely to live, if you had that kind of cash to burn, is in a small terraced house in Grimesthorpe with three strangers, one of whom is sleeping in what used to be the living room. But Ali*, a Yemeni refugee in his 50s, claims Sheffield Council spent almost a year and a half forking out £907 a month so he could do just that.

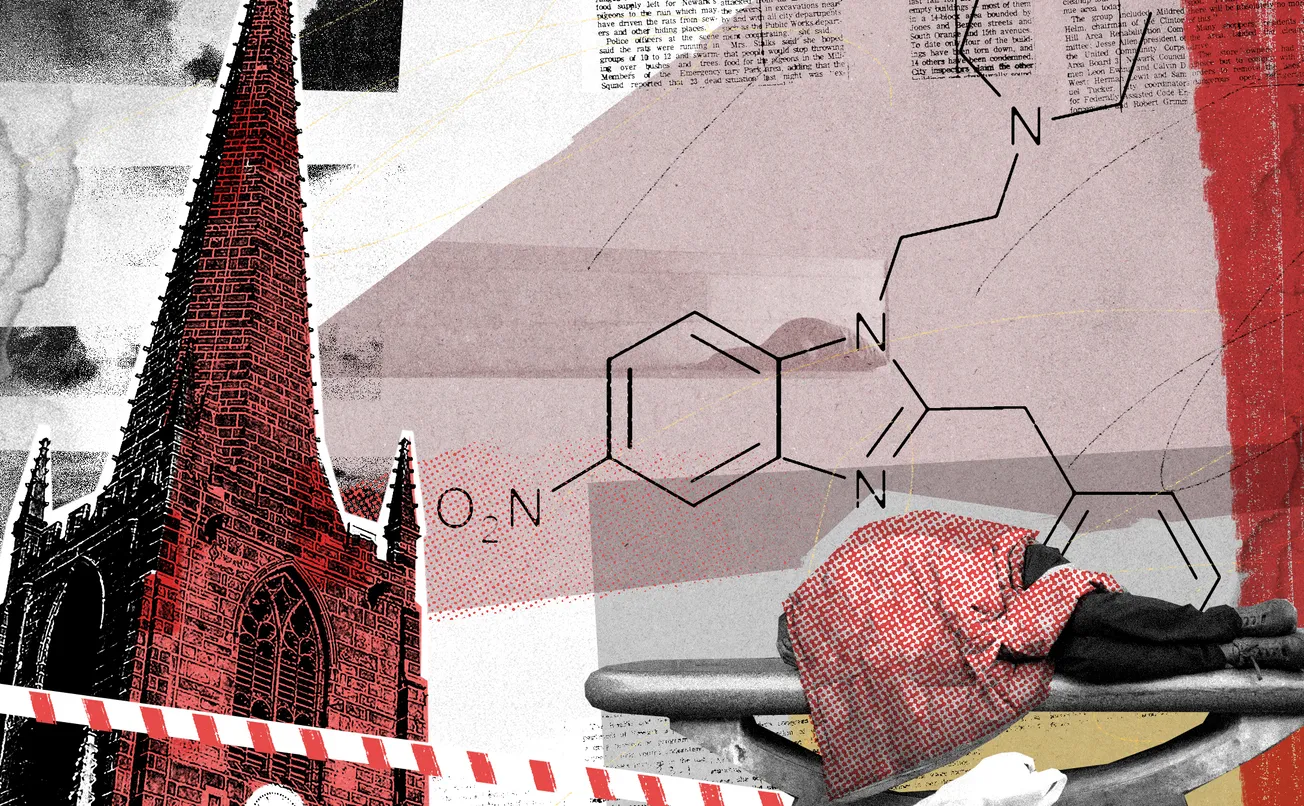

In the council’s defence, it didn’t have a choice in the matter. It had nothing to do with the decision to house him there, despite the fact it was footing the bill. Instead, Ali was housed by a company called Green Bridge Community Housing, which has quickly become the biggest local player in a little-known but hugely profitable industry: exempt accommodation. The council handed Green Bridge more than £6.6 million in housing benefits over the last financial year — but how much bang are we getting for all those taxpayer bucks? That’s today’s story.

Editor’s note: From start to finish, this story has taken almost a year to complete. We originally intended to publish a piece on Green Bridge all the way back in May but, after their lawyer sent us a four-page letter threatening to take us to court, we decided to make extra sure we could back up everything we’ve written here. It would have been far easier (and less nerve-wracking) not to publish at all, but our duty as journalists is to find and report the truth, even if some people would rather we didn’t. If you don’t yet subscribe, please join today — stories like this are only possible because of our paying members.

Your Tribune briefing

🤝 Sheffield Council has bought the Grade II-listed Salvation Army Citadel building in the city centre, which has stood empty and dilapidated since the charity moved out in 1999. In a joint statement, Cllr Ben Miskell and the building’s former owner Robert Hill said the council and his company, Tandem Properties Ltd, were “pleased to have reached terms to settle court proceedings” and that both parties “look forward to proposals then being progressed to see the building brought back into use”. Earlier this year, The Star reported that the council had served Tandem Properties a notice ordering it to repair the building. At the same time, Tandem Properties has been in the process of taking the council to court over “deliberate concealment”.

🏗️ Major developer Capital&Centric has got the ball rolling on the next phase of its decade-long masterplan for “Mesters’ Village”, near Devonshire Quarter, by purchasing a site on Fitzwilliam Street where it intends to build 200 new homes. In 2019, C&C announced a grand vision for the area that would involve 2,500 new homes, although it has so far completed just 97. The existing flats are split across three buildings: two Grade II-listed former cutlery works — Eyewitness Works and Ceylon Works — and “industrial-style new build” the Brunswick.

🥕 Now Then spoke to social enterprise Food Works about new plans to put more than 1,650 square metres of glasshouses in Graves Park to good use. Norton Nurseries originally opened in 1983 and was used by the council to grow bedding plants for the city’s parks until the mid-90s, when it shut down due to high running costs and reduced demand. Working alongside the council, the University of Sheffield and a “new community of growers”, Food Works hopes to give them a new lease of life growing food for local residents.

‘Guaranteed Rent, No Worries’: How housing provider Green Bridge profits from Sheffield’s most vulnerable

*Some names changed to protect anonymity

In November 2021, the Home Office gave Ali*, a Yemeni refugee in his early 50s, both leave to remain in the UK and a few short weeks to leave the hotel it had placed him in and find somewhere else to live. Thankfully, a friend and fellow refugee told him about a company called Green Bridge Community Housing that could help. Ali rang them and was promptly invited to their office in Burngreave, where he says he “filled out some kind of form” and was assured they could offer him temporary accommodation. “They told me the council can pay my rent, so it didn’t matter how much it was,” he says. He later discovered his room in a small terraced house in Grimesthorpe was costing the council £907 a month.

What justifies the price tag? The house isn’t in a sought-after neighbourhood like Kelham Island — just round the corner, I pass four dead rats on the pavement in quick succession — and the best that Ali will say for it, as someone who clearly doesn’t want to seem ungrateful, is that it was “not that good, but fine”. Only eight months before he moved in, it was bought for the modest price of £65,000. The landlord that snapped it up is called Green Bridge Group Ltd: a real estate company with the same two directors and registered address as Green Bridge Community Housing.

So why had Green Bridge set Ali’s rent so high? And why on earth was the council being compelled to pay it in full? After all, if someone eligible for housing benefits was renting a room in a shared house on the private market, the council would only pay £80.55 a week towards their rent — a little over £320 a month. But Green Bridge isn’t in the business of renting rooms on the private market; it’s not even a normal temporary accommodation provider. Instead, it offers something called “supported exempt accommodation,” intended exclusively for society’s most vulnerable groups. (The word “exempt” in this phrase refers to the fact that its tenants are exempt from the normal cap on benefits; hence the immense sums of taxpayers’ money that Green Bridge can receive on their behalf. The word “supported” refers to the intense, personalised care it’s supposed to be offering in return.)

The list of groups eligible for exempt accommodation, other than refugees, includes people with addiction issues, serious mental health problems and those who are fleeing domestic abuse. It’s intended as a short-term stepping stone to a more stable, independent life. On Green Bridge’s website, the company states its mission is to help people “(re)integrate into society,” by providing both housing and support programmes tailored to their immediate and long-term needs. “Our philosophy is to offer engaging, non-judgmental support through the provision of interventions that fulfil not only the needs of the individual, but also their wants and aspirations,” it reads. Elsewhere, it describes Green Bridge as a “bridge to a brighter future”.

Despite only having operated in Sheffield for a few years, Green Bridge has already developed a very different reputation among local charities. Staff from four different organisations supporting homeless people or refugees told The Tribune they had serious concerns about the service this provider offers. One tells me that, around three years ago, Green Bridge tenants began approaching her charity in the hopes of moving out. “We were getting a couple every month,” she recalls. In some cases, it was simply because they wanted to work, which tenants of exempt accommodation are not permitted to do. “But many of them also complained about substandard properties, not getting support and antisocial behaviour. We were told the homes were bad, and the support was even worse.” An employee at another charity concurs. “We’ve had people coming to us, wanting to move out and saying they never even saw their support worker.”

When first contacted by The Tribune in May, Green Bridge instructed Bindsman LLP — one of the country’s leading law firms, based in central London — to send a four-page letter threatening to take us to the High Court. The letter insisted that Green Bridge’s housing stock is “seen as market-leading” — its properties are “well-maintained” and “fully furnished to a high standard,” we were told — and that all of its tenants receive a weekly visit from a support worker, who is “required to log these appointments electronically as having taken place”. Following this original request for comment, one of the company’s directors abruptly wiped all previous posts from his personal LinkedIn page.

After spending the last five months gathering more evidence, The Tribune approached Green Bridge again and, once more, received a four-page letter from Bindsman LLP. “It appears that your newspaper may be approaching this with a predetermined narrative that paints Green Bridge in a negative light,” it reads, something the firm claimed was “disappointing” given the many lives Green Bridge has positively impacted. “Growth of support services in response to rising homelessness is not something to be criticised, but rather celebrated, as it helps more people in need.” While the letter stated its contents was off-the-record and only attributable to “sources close to our client” — something The Tribune did not agree to in advance and will therefore not honour — it also provided a statement from a Green Bridge spokesperson:

“Green Bridge is passionate about supporting vulnerable people and has played a key role in reducing homelessness in the community. We have supported a large number of people, helping them transition from homelessness to stability, providing employment opportunities, apprenticeships, and actively contributing to local causes. We always act quickly in response to residents’ concerns and have the highest standards for accommodation, with mechanisms to ensure that these are upheld.”

Having spoken to several current and former Green Bridge tenants, as well as a former employee who left the company recently on good terms, this is not the impression I get. A young mother currently housed by Green Bridge tells me she only sees her support worker for “five or ten minutes” once a week. A former tenant tells me he was so desperate to leave his Green Bridge home that he made himself intentionally homeless, sleeping on the street for several days, so that he could get housed by another organisation.

Comments

Sign in or become a Sheffield Tribune member to leave comments. To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.