“We’ve got three left, this one’s called Foreskin,” says Brad Cadman, the lead singer of Richard Carlson Band. This is Jarred Up, a regular night at Sidney and Matilda, and RCB are the first band on. As you might expect from a band named after an obscure film and television actor from the 1950s and 60s, they are what you might call unique. First there’s the sound, which Cadman later describes to me as “organised chaos”, and I’d describe as a cross between American slacker band Pavement and Captain Beefheart. And then there’s the look. On stage they present as a ramshackle collection of oddballs and misfits, plus a saxophone player. The guitarist has a trenchcoat on and hair like my mum had in the 90s, while for some reason the keyboardist has a cardboard Michael Barrymore mask fixed to the front of his instrument. When I ask Jarred Up promoter James Watkins where the band are from, he turns to me and says: “Mars?”

The basement room at Sidney and Matilda, in Rivelin Works in the city centre, has a capacity of just 150. It’s one of many former industrial spaces that have been repurposed into music venues in Sheffield. The low ceiling and faint smell of damp make for a claustrophobic, intense atmosphere. Two large red speaker stacks stand sentry at either side of the tiny, cramped stage. When the Richard Carlson Band come on stage there are just a few dozen people in the room, but the band doesn’t seem to mind. Despite its provocative title, I reckon Foreskin is one of their best songs — bluesy and melodic, it stands out among their more experimental fayre as something I could imagine being played on the radio.

When I catch up with Brad Cadman, who is actually from Rotherham rather than Mars, he assures me he harbours no hopes of fame, but just enjoys being creative and playing live. “What else would I be doing on a Wednesday night?” he asks. “Places like this give me the opportunity to express myself.”

Sheffield is blessed when it comes to independent music venues: Delicious Clam, the Dorothy Pax, Hatch, Gut Level, the Washington and the Hallamshire Hotel. But the economic misery of recent years is pushing many close to, if not over, the edge. A recent report from the Music Venue Trust found that on average two small music venues close every single week. In Sheffield in recent years, we have lost the Abbeydale Picture House, DINA on Fitzalan Square and Make Noise Studios off Shalesmoor. It’s not exactly an industry to get rich quick in — the Music Venue Trust report found that 43% of small music venues made a loss last year, while the average profit margin was just 0.48%.

Mark Riddington has been the manager of Sidney and Matilda since 2023. When he joined they were only open on Friday and Saturday but now they can be open up to six nights a week. The venue is in a better place now than it has been since it was founded in 2018, but Mark says it's been hard. Diversifying the gigs and club nights they offer into different musical styles has helped. As has managing to source a beer they can sell for just £4.49. This Sidney and Matilda-branded lager has been affectionately nicknamed “the cost of drinking crisis”.

But this year things are going to get ever tougher. First they will have to find the money to cover the minimum wage going up (which Mark says Sidney and Matilda strongly supports) and the increases to National Insurance. Then, they will have to find £15,000 to cover the recent changes to business rate relief, after music venues saw their relief cut from 70% to 40% in the last budget. Plus, there’s the ever-looming risk of a noise complaint — something which becomes more likely as the city centre fills up with flats. “You are only ever one noise complaint away from having a court case on your hands,” he says. “It’s a challenge.”

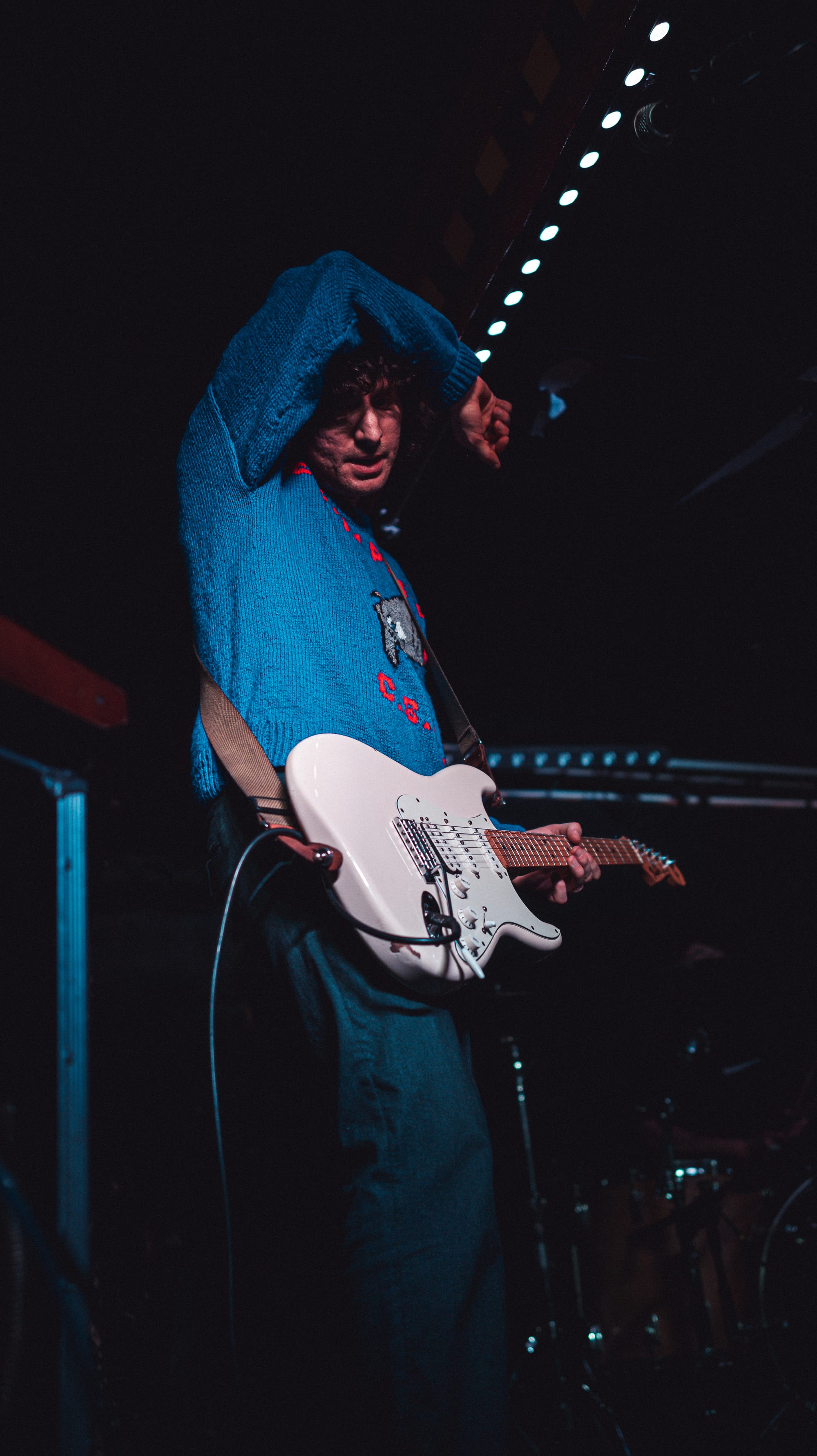

After Richard Carlson Band come Y, the new band of Fat White Family guitarist Adam Brennan, playing their first gig outside London. Singing duties are shared between Brennan and bandmate Sophie Coppin, while they are accompanied by bass, drums and sax (saxophones seem to be having a moment). Y make a hell of a noise, if a little rough around the edges. Then there’s Keg, a seven piece from Brighton who the NME recently described as “muscular art punk”, whatever that is. They are easily the most confident and accomplished band of the three on stage tonight. Fitting their seven members on to the tiny stage is no mean feat, but adds to the intensity of the atmosphere. By the end, the room is almost full and charismatic lead singer Albert Haddenham is drenched with sweat. You can see why people are getting excited about them.

On a bright and sunny Wednesday afternoon I take a short stroll to Victoria Quays and the Dorothy Pax. It’s the same stroll I made one July day in 2021 to visit Canal-Lines, the Dorothy Pax’s outside Tramlines stage. There, for the first time I saw Henge, a band that pretend to be aliens visiting the Planet Earth named Zpor, Goo, Grok and Nom. At least I think they are pretending. Their show that day was so strange, new and riotously entertaining it remains one of the greatest things I’ve seen in my entire life.

Walking down the steps into the cavernous interior, the bar opens out into a surprisingly large space, the bar to the right and a small performance area to the left. At capacity the Dorothy Pax can fit in just 60 people, making it one of the smaller small venues in the city. The main face of “the Pax” (as everyone calls it) is Richard Henderson, who founded it in 2017, originally as a cafe and bar but after 2020 as a live music venue as well. Sat hunched over a laptop on a large tables near the bar, he and his assistant Briony Tuplin are busy programming the next few months and looking nervously at their financial projections. “Don’t ever, ever, ever start a small music venue,” says Richard as I sit down.

It quickly becomes clear the Pax has a philosophy. First of all they always pay people. “No one has ever played down here and not been paid for their work. We don’t think that is the way the industry should be operating,” says Henderson. This means that all artists are paid a guaranteed fee, while they always have a paid sound engineer and sometimes even a paid lighting technician as well. Second, they prefer to put on free shows wherever possible. “We firmly believe you should be able to borrow £20 off your Gran, or whoever, and come down here to have four or five pints with your mates,” he says. “Access to art shouldn’t be dependent on the thickness of your wallet.”

Which all sounds lovely, but if they’re still having to pay all artists, and not charging an entrance fee for most of their gigs, where is the money coming from? In the past, the shortfall would have been made up from bar sales. But what Richard calls the “cost of living clusterfuck” has reduced bar spend by 60% per head, he says, meaning that model has completely broken down. “Wet sales used to guarantee fees for the artist and the engineer,” he says. “But because of the lower bar spend, those margins have got tighter and tighter. It’s extremely difficult at the moment.”

On top of that, the Pax has seen its electricity bills double, from £500 to £1,000 a month. And Henderson hasn’t taken a wage out of the business in seven years. “We’re effectively a not for profit company and have joined the voluntary sector,” he says. “It’s a labour of love but it’s not sustainable forever.”

Which raises the question: why does he do it? “It’s great fucking fun,” he responds. “Imagine going to four or five gigs a week and seeing some amazing talent.” But as well as that he also thinks it’s important. For lots of bands who have played here it was their first ever paid gig. And half a dozen artists who have played here have gone on to play the main stage at tram lines. The conveyor belt argument that without small venues you would never get big stars is often made, but Henderson says he prefers to see their role as research and development, allowing bands to experiment and express themselves creatively.

In an attempt to fight back the Pax has launched a Patreon, an online tool which allows people who support something to donate money to it. So far 100 people have signed up. But a much bigger prize would be to do what the Music Venue Trust has suggested: a levy on stadium tickets. At the moment, when huge bands play Wembley Stadium, a portion of the ticket sales goes to grassroots football. The MVT are proposing to do the same thing but for all big music venues, like Sheffield Arena and the new Coop Live Arena in Manchester.

Some bands have even taken it upon themselves to do this off their own bats. On their forthcoming UK tour, Coldplay have agreed to donate 10% of their earnings to the Music Venue Trust. “I never thought I’d say ‘god bless Coldplay’, but there we are,” says Henderson.

Luckily, there are ways ordinary gig goers can help. Jarred Up promoter James Watkins says that people should buy tickets in advance when they can, giving venues confidence that gigs can go ahead. And seasoned Sheffield gig goer John Mounsey says his biggest bugbear is people not supporting their local venues. Many bands don’t include Sheffield on their tour itinerary any more, so when they do and people don’t turn up in large numbers, they are less likely to come back. “It really is a case of use it or lose it,” he says.

But there’s good news as well. The recent return of the Hallamshire Hotel on West Street has provided the city with another good new small venue which is proving popular. All in all, Mounsey says the Sheffield music scene is in reasonably good shape, but would benefit from another one or two venues. With a few more regular gig goers, he thinks that’s easily achievable.

Back at Sidney and Matilda, I catch up with Adam Brennan of Y. They played recently at the 150-capacity Brixton Windmill, a pub credited with the resurgence of the South London guitar rock scene. “I like small venues,” he says. “I like to see people’s faces and see the reaction. It’s real.” He accepts that the music scene for both small venues and aspiring musicians is “on its arse”, but the thought of giving up is unbearable. Without places like Sidney and Matilda and others, he says the music industry would be full of "products" created by the major labels. “There’s no money in it and it's a lot of graft,” he says. “But you do it because you love it.”

Jarred Up is the first gig I’ve been to in a place like this for some time. I’m not sure all of the music is entirely to my taste. But the connection and communality of live music in an intimate space like Sidney and Matilda’s basement is difficult to beat. The smell of beer and sweat and the thud of bass in my chest is reinvigorating, even for a 40-something up long past his bedtime.

American novelist Kurt Vonnegut said that “practising any art, no matter how well or how badly, makes your soul grow”. We all have an interest in having small music venues where people can express themselves. Not because they might become the next big thing. Just because it’s good to make noise.

Many thanks to Ollie Franklin for allowing us to use his photos in this piece.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.