“This is a diary of events in note form and to be clear I have never felt the need, in 30 years of employment, to create such a record.”

That opening line was penned by Carl Hitchens in 2018. Hitchens, the former head of machining at the Nuclear AMRC, sent me the diary in place of a conversation. He told me he just couldn’t face reliving such a painful period.

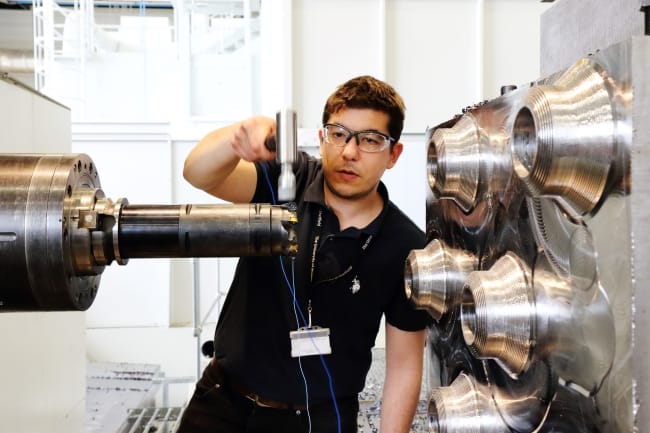

The Nuclear AMRC was set up in 2009 with a simple mission: to help UK manufacturers win work in the civil nuclear sector. As well as research and development into nuclear technologies, the centre also worked with British firms to help them design and build components that could be used in nuclear power plants. Ostensibly part of the University of Sheffield, the Nuclear AMRC enjoyed a large degree of autonomy from its parent organisation.

As we found in our piece last year, the Nuclear AMRC never found its task easy. Continuing concerns about the safety of nuclear energy, the government's refusal to commit to its future, and newer technologies like small modular reactors (SMRs) all created a challenging environment to navigate. Despite this, all indications are that, in its early days, the Nuclear AMRC was a fairly happy ship.

So how did something that was meant to put South Yorkshire at the centre of a generational transformation of the UK energy sector fall apart in a few short years? How did the Nuclear AMRC go from being touted as a huge growth success story, to being all but shut down? Carl Hitchens’ diary — and the recollections of his colleagues — are now allowing us to answer that question.

The diary

The turning point, according to those we spoke to, was in 2017, when former CEO Mike Tynan left to be replaced by Andrew Storer. Storer had joined the Nuclear AMRC from Rolls-Royce in 2015, but when he was promoted to CEO in 2017, the management of the organisation quickly became much more confrontational. Storer could be hostile and intimidatory and would threaten to sack people over relatively minor issues like missing paperwork, we have been told.

In 2018, Hitchens was so worried that he began keeping a diary of the behaviour he either personally experienced or saw. It’s a record from the time of what was happening inside the organisation. The diary is written in a matter of fact tone, which in some ways accentuates the sense of an organisation falling apart*:

December ST leaves – the job and attitude is too much and not worth it anymore

DA has serious HR issue regarding a clash with Jay Shaw and steps down and returns to my research group…

BB resigns leading academic and leaves £2 million electron beam cell with limited technical support

January CJ resigns, only equipment qualification member of staff and puts the Derby iHub development at risk

The diary also testifies to an inner sense of turmoil. “I find myself constantly tense while at the centre and experiencing anxiety attacks. Disturbed sleep is increasing and I am constantly tired,” reads one entry.

As well as Andrew Storer, the other figure who features most prominently in the diary is Jay Shaw, who Storer promoted to be the Nuclear AMRC’s programme director in 2018. The two worked closely together throughout Storer’s time as CEO. (One source we spoke to went so far as to describe Shaw as Storer’s “henchman”.)

In July 2018 Hitchens’ diary notes that three staff members were “left in tears due to behaviour of Jay Shaw” while at the same time another of Jay Shaw’s staff personally asked Hitchens for advice and support on how to cope with his boss’s behaviour. In September the same year, Hitchens writes that Shaw “described me as incapable in front of other staff” because he did not know the exact number of live projects the Nuclear AMRC had running off the top of his head. The same month, Shaw began organising a weekly Monday morning meeting which was “negative, harsh and unprofessional”, adding that its use to highlight errors made by staff was “bordering on abusive”. In June 2019, he writes: “I can only conclude that Andrew Storer and Jay [Shaw] have built a culture of bullying and intimidation and appear to enjoy it.”

Hitchens didn’t want to talk, but he did send us this quote. “In 30 years of working in industry, I have never seen such a high turnover of staff and such a high percentage of a workforce registered as sick due to mental health issues,” he says. “I particularly found it disconcerting that when I highlighted my concerns, they were ignored by the HR department.”

“I just assumed naively that the procedures would be followed”

Hitchens wasn’t the only one who had concerns about the culture fostered by Storer and Shaw. David Anson, 62, joined the Nuclear AMRC in 2015, rising through the ranks from project manager to principal engineer. Anson says that within a year of Storer’s appointment, he began to become disillusioned with the culture that Storer and Shaw were creating. He tells me he had his first run-in with the new regime in 2018, when Shaw hit him with a series of what Anson believed were unreasonable and unnecessary demands just 48 hours before a major bid was due to be submitted. Their relationship never recovered.

Anson was so worried about this culture that on 1 April 2021, he raised a whistleblowing complaint with the university. “Being a mental health champion I was becoming increasingly concerned about widespread bullying and a toxic culture coming from the top,” he says. Anson had a 90-minute long conversation with Dave Petley, the member of the University of Sheffield’s university executive board (UEB) with responsibility for the Nuclear AMRC. Petley assured him he would take his concerns seriously and that he was protected under whistleblowing rules. “My understanding was that because of the seriousness of the allegations action would be taken,” Anson says. “I just assumed naively that the procedures would be followed.”

Petley left the university in August 2022 to become the Vice Chancellor of Hull University, a position he still holds. Having heard no further, Anson raised another issue with Petley's successor Geraint Davies. It was only then — two years later — that he found out that nothing had been done about his complaint. “Two years had passed and personally I felt devastated,” says Anson.

In May 2023, during mental health awareness week, Anson posted an infographic about toxic workplace behaviours on the organisation’s Slack channel as part of his role as mental health champion. Many reacted to the post and some left comments. One person gave a very detailed response. “Speaking from my own experience over five years working at the Nuclear AMRC, here are some specific toxic workplace behaviours and policies that I have experienced that have had a negative impact on my mental health,” the staff member wrote. As well as uncertainty, isolation, a lack of feedback, unclear responsibilities and a lack of support, he identified bullying as a main reason for his unhappiness. “The aggressive and disrespectful tone from a key management figure” had led to him experiencing fear and anxiety and panic attacks, needing time off work to recover. The comment didn’t mention anyone by name but everyone knew who it was about: Jay Shaw.

“Bully boy tactics”

James Turner, 64, joined the Nuclear AMRC in 2011 and worked there until October last year. He began as an advanced machine tool operator before later being promoted to shop floor supervisor. For Turner, the “Jay Shaw regime” was the heart of the problems. “I have been in engineering for 45 years and he [Shaw] was an absolute nightmare,” he says.

Turner paints a picture of Shaw as controlling and unreasonable. “He made it difficult for people to work there,” he says. “You could never do anything right. You couldn’t work with him, you couldn’t reason with him,” says Turner. “A lot of good people left because of his bully boy tactics.”

Turner also remembers Shaw having a disagreement with the maintenance manager when they were doing a risk assessment about returning to work after Covid. “The next day he asked me whether I had seen the disagreement,” he says. “He told me that ‘if [the maintenance manager] thinks he is getting the better of me he can think again’. I said to him ‘do you think we are in a playground here, we are supposed to be working together’. After that he made the maintenance manager’s life hell and because I wouldn’t back him up he made my life hell too.” Turner says after this he was constantly told by Shaw to take on new responsibilities but never given either pay rises or a new job title.

After Turner left in October last year, he got a job lecturing in engineering at Chesterfield College, which he loves. He is currently doing an assessor's qualification which he says he would never have got that opportunity at Nuclear AMRC. “If someone says you can’t do something often enough, you end up believing it,” says Turner. “But I came here and realised I was really good at it. Chesterfield College have shown me a lot of support. Why didn’t he?”

“I am not bitter. I am much happier. He’s done me a favour,” says Turner of his life outside the Nuclear AMRC. “But a lot of people put a lot of effort into that for it to be ruined by him.” Turner’s opinion is that Shaw was “an excuse for a director. He hurt a lot of people and he brought Nuclear AMRC to its knees.”

So was the key reason the Nuclear AMRC failed the unhappiness of its staff, brought on by its leadership? One former staff member, who worked in business development at the Nuclear AMRC from 2013 until 2019 and asked not to be named, thinks so. Within three months of Storer getting the top job, two directors had left the organisation, effectively being forced out by the new regime, he says.

The Nuclear AMRC’s main strength was its talented staff, many of whom were among a handful of people in the world with their knowledge and skills. However, instead of using this priceless resource, the former staffer claims Storer and Shaw set about undermining it. Senior managers would be dressed-down in front of their colleagues while others would be sidelined or spoken down to in meetings. As a result, a “weird sense of fear” developed which led to numerous people feeling their jobs had become untenable and leaving, him included. Some of the behaviour was probably illegal, he reckons. “I think some of it amounted to constructive dismissal,” he adds. When the news came last year that there were going to be 100 redundancies at the Nuclear AMRC, he says he was “disappointed but not surprised”.

No comment

We put the questions raised in our piece to all of the key individuals named in this story. Each gave us the same reply: No comment. (Jay Shaw excepted — who didn’t reply at all). The University of Sheffield, which had oversight of the Nuclear AMRC, told us they were unable to comment on individual circumstances. However, a spokesperson said: “The University takes reports of bullying very seriously and has established processes to investigate complaints, including a whistleblowing procedure. We encourage staff to challenge or report unacceptable behaviour and offer support to anyone who wishes to raise a concern or make a report.”

As of today the Nuclear AMRC still exists, but it’s a shadow of its former self. James Turner says he knows people who are still working there who describe it as “a shitshow”. Many of those who led the organisation during this period have now moved on. Andrew Storer has set up his own company called NucCol, while Jay Shaw moved to Forgemasters and is now the general manager of their machine shop. Dave Petley, who didn’t take forward David Anson’s complaint, is now the Vice Chancellor at the University of Hull.

By contrast, David Anson and Carl Hitchens have both left the sector, for roles that make no use of their expertise. Anson, formerly a principal nuclear engineer, is now training to be a bus driver. When I speak to him about his new role I can tell he's slightly embarrassed about it, although he has no need to be. Hitchens, the former head of machining, runs a craft café with his wife in Scarborough.

No one expects workplaces to be conflict free. When you are trying to do something complicated and important, tensions are inevitable, even healthy at times. But healthy workplaces are ones where conflict is managed, where there are established procedures for when problems do arise and — crucially – where those established procedures are followed. None of this appears to have been the case at the Nuclear AMRC.

Where does this leave the nuclear industry in South Yorkshire? The Nuclear AMRC was meant to put our region at the epicentre of the clean energy future. Tens of millions of pounds of public money were ploughed into it over 15 years. By any measure, it has failed — undone by a culture that pushed many of its brightest and best away. It feels like we are owed more of an answer than simply: no comment.

*names have been anonymised.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.