In a dark corner of Black Swan Walk, a deserted cul-de-sac off Fargate, stagnant puddles of water pockmark the floor and three industrial-sized bins are huddled together in one corner of the courtyard. It’s a desolate place for someone to spend their last moments. On Saturday 16 November, staff at Boots discovered a woman’s body here. She was only in her forties.

Tragically, this was just one of three homeless deaths in Sheffield city centre over a devastating ten-day period in November. A few days after the woman’s body was found on Black Swan Walk, another woman, again in her forties, was found in a car park stairwell near Union Street; both women were well-known to the various services that help vulnerable people in Sheffield. The third death, however, was a man who was not known to anyone. He may have been new to the city, suggests Tim Renshaw, chief executive of the Archer Project charity. He could have been somebody’s son, brother, dad or uncle. They may still not even be aware he has died.

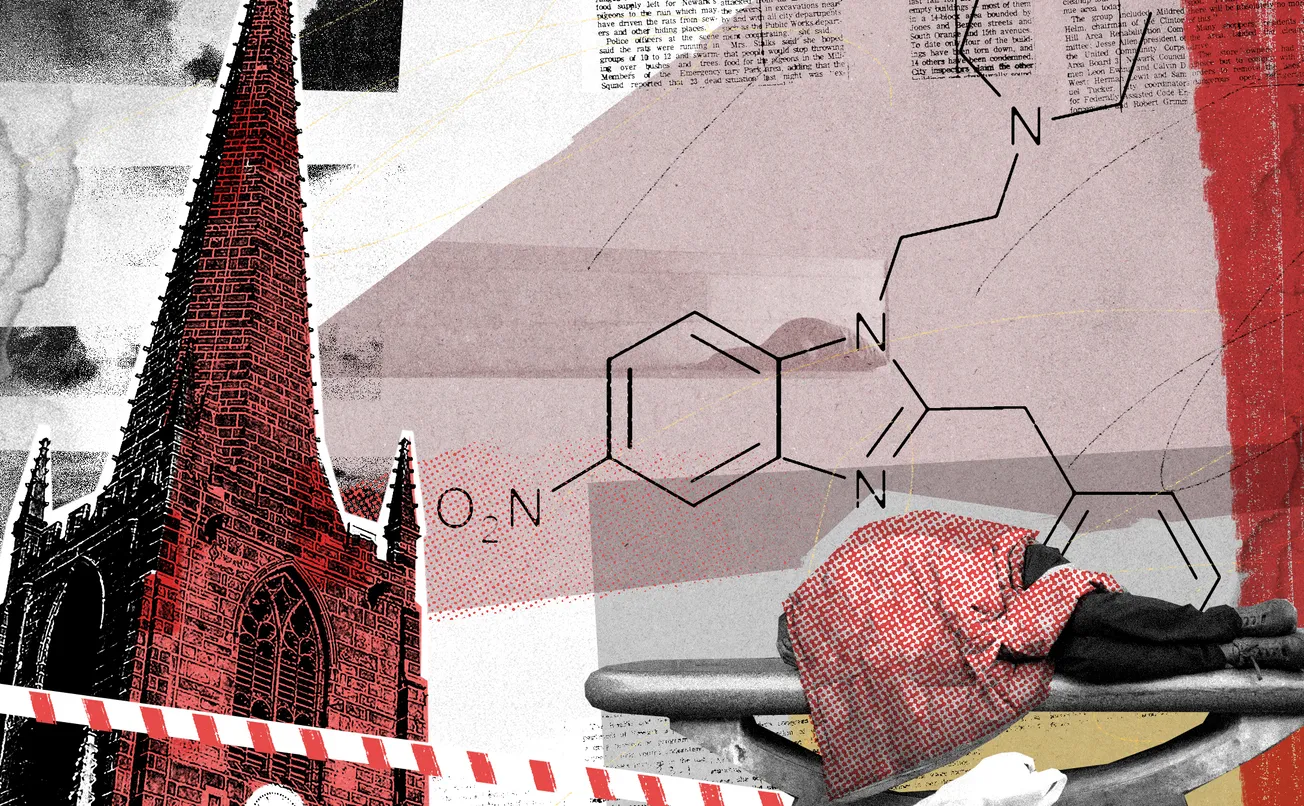

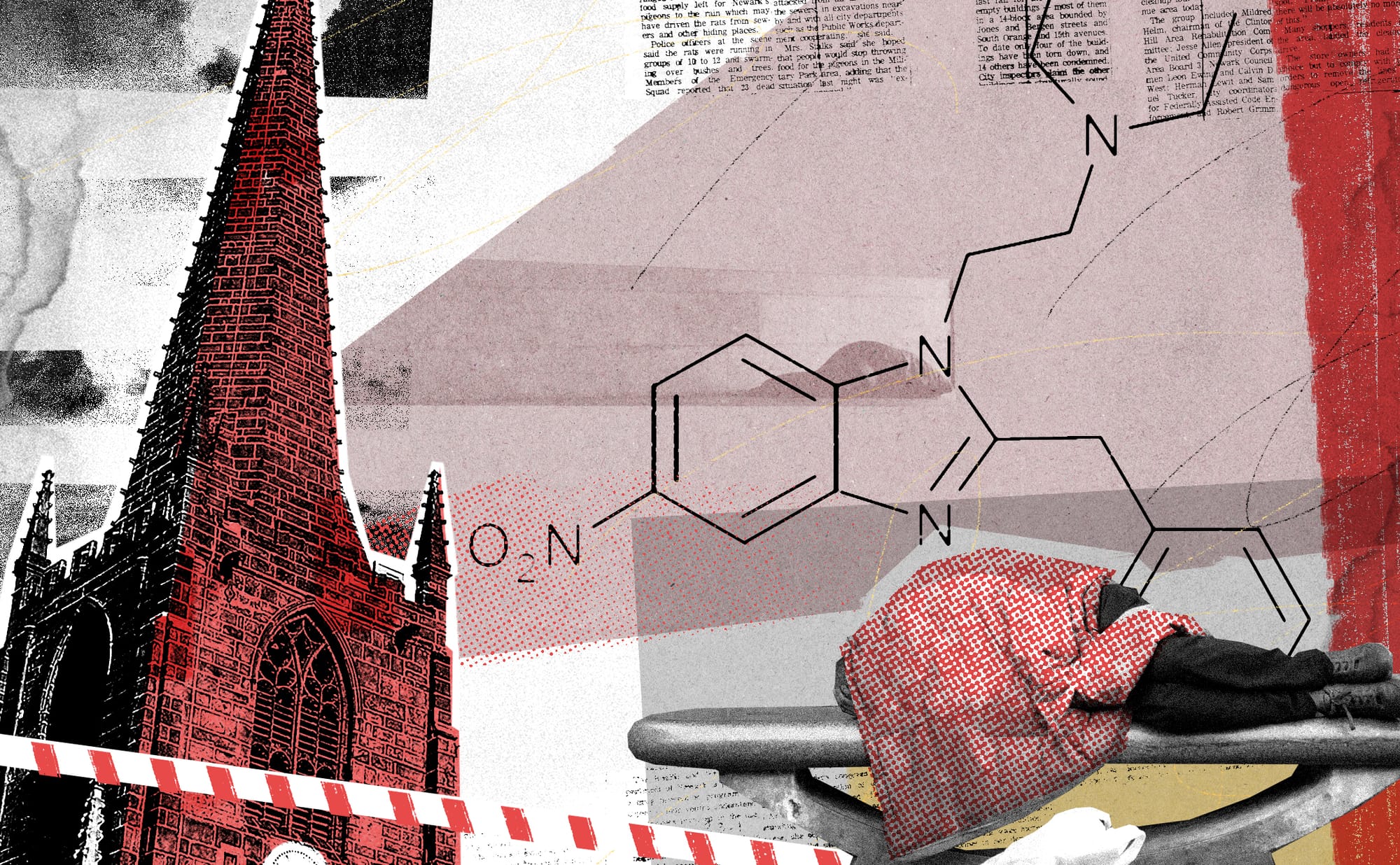

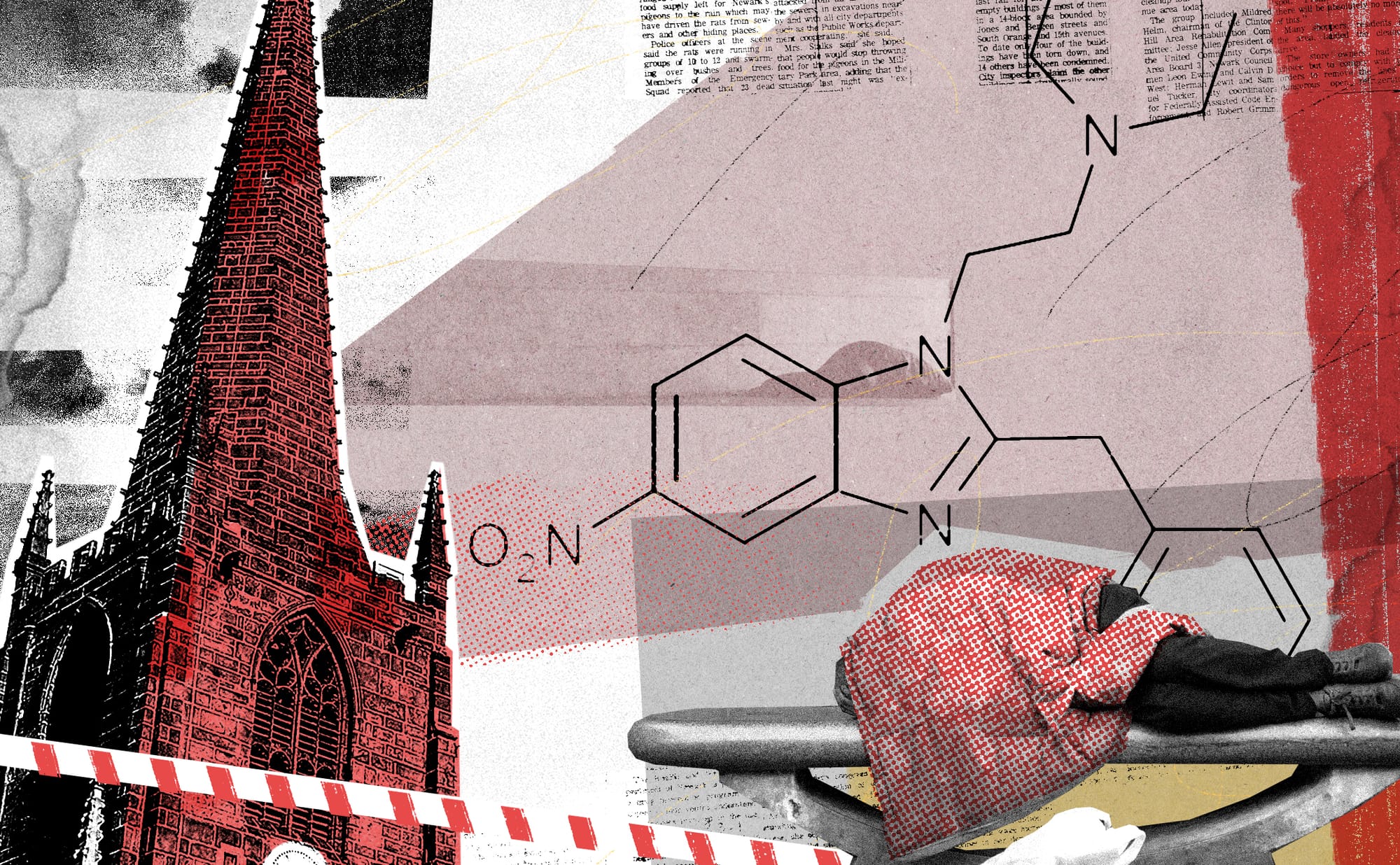

Death is ever-present in the homeless community. The average life expectancy for a man living on the street is 45 years old. For a woman, this drops to just 43. While the figures for 2024 have not yet been compiled, this year has almost certainly been worse than most. As well as the three people who died in November, in July, a man’s body was found near Sheffield Cathedral, while just a few days later, another man was found on the steps of Sheffield City Hall. Until the inquests take place, it’s difficult to say exactly why these people died. But many in the Sheffield services that work with vulnerable people in the city centre believe that a type of new synthetic opioid called nitazenes could be responsible for some, maybe even all, of these deaths.

Since July 2023, nitazenes have been linked to 284 deaths in the UK, according to National Crime Agency data. Last summer, 21 people died in Birmingham within the space of just three months. Compared to both heroin and other synthetic opioids like fentanyl, the drug is deadly. One variant, etonitazene, is said to be 500 times stronger than heroin. Warnings about the new drugs were issued by the government and Sheffield City Council earlier this year.

Since the late 1980s, the Archer Project has been a regular place of shelter for people in the city centre who have nowhere to go and nothing to do. It now helps people transfer from street homelessness to a settled life, offering health and well-being services and employment opportunities. Tim Renshaw tells me that staff at the project knew the two women who died well. Quiet and deferential, the woman who died in the car park stairwell was present most nights in the city centre. She had been provided with accommodation many times, but always ended up back on the street. In her case, staff were aware that there had been a life event that led her to leave her previous, more stable life of employment for a life of escape. “She never got away from that, and once she was into heroin use it dominated her life until the end,” he says.

The woman who died on Black Swan Walk was much less predictable. “In one moment she loved you and thought you were the best thing ever,” he says. “But as soon as you said we can’t do that she would say, ‘You never do anything for me.’” For all her complexities, staff at the Archer Project remember her fondly, and believed that with help, she could turn her life around. Sadly, that wasn’t to be.

Chris Lynam, a peer mentor at the Archer Project, says that many people end up in this situation due to past trauma. Born in Dublin, Lynam was physically and sexually abused when he was a child, which later led to him becoming addicted to heroin. Moving to South Yorkshire ten years ago, he ended up in prison, but found a lifeline upon release by working as a mentor at the charity. Eight years on, he’s still there. He says the vast majority of the people who use the Archer Project will have had some kind of “adverse childhood experience”, which can include physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or living in a household with domestic violence, substance abuse, or mental health problems. “I often say that instead of asking people ‘Why the hell are you doing what you are doing?’, we should be asking them ‘What happened to you?’” he says.

The majority of clients who use the Archer Project are addicted to heroin, meaning they are at serious risk from the rise of nitazenes. Most heroin addicts are well aware of their limits and tolerances because they're dealing with it every day. With nitazenes, or any synthetic opioid, the difference between taking a lethal and non-lethal dose is minuscule. “A lot of the time you hear about addicts dying, they just didn’t know what they were taking. People think they are buying heroin,” says Lynam. If these new drugs are dangerous for seasoned drug users, then for less experienced users, there is usually only one outcome. “If you try for the first time, and you try that stuff, you’re dead,” he says.

One side effect of regularly using synthetic opioids is so-called crocodile skin — endemic necrotic scar tissue around the areas of injection — and ulcers so bad they can lead to amputations. If there is a decent chance you might die or have one of your limbs amputated, why on earth do people take them? “The pro is that it’s good,” says Lyman. “I’m a recovering intravenous drug user, and if I’d have known there was incredibly strong synthetic gear that people have died from, I would 100% score it. I would have sought it out. That’s the insanity of addiction.”

When I heard about this spate of deaths, I felt like there had been almost no response to them other than a fatalistic shrug. Among the professionals charged with helping people get clean and off the street and preventing unnecessary deaths, there have been questions about what went wrong. But Tim Renshaw says that before those questions are asked, we need to first stop seeing people on the street as a problem to be solved, but as individuals with complex lives and needs. “You can have all the systems in the world in place, but they are not going to help that person recover,” he says. “What’s needed instead is to listen to them on a human level.”

This approach also means marking each death and helping the people who were with that person on the street to mark that death too. The people who live on Sheffield’s streets are a community, and deaths within this group are felt keenly, adding yet more trauma to people’s already difficult lives. However, Lynam says this mourning doesn’t normally last too long. “They will get upset, but they also move on pretty quickly. It’s seen as an occupation hazard,” he says. “That’s not a normal reaction, but it isn’t because they don’t care. They have just seen it too many times.”

Recently, there have been concerted efforts to change this. Last year, the Archer Project organised a small service in the Cathedral for someone who had recently died on the street. People from the homeless community were able to light a candle and say that his life was important to them; to grieve and to mourn. Since 2017, an organisation called the Museum of Homelessness has been attempting to log every death of a homeless person that has taken place in the UK. In a report published in October, they revealed that across the UK, there was a 42% increase in the reported number of people who died while rough sleeping in 2023, compared to the year before (155 vs. 109). They said the figures were evidence that “an emergency” was taking place on our streets.

Tim Renshaw says the deaths also raise questions about whether Sheffield should consider providing safe spaces for people to use drugs. At the moment, services like the Archer Project hand out needles to reduce the spread of HIV and Hepatitis, but their clients still have to go away and use the drugs elsewhere. Many involved in working with vulnerable people question whether this is the best way to tackle the problem, but some members of the public see it as a moral issue of condoning drug use.

And then there is the Public Space Protection Order (PSPO) that is due to come in next year, which will allow police to remove people involved in anti-social behaviour (such as drinking and begging) from the city centre for 24 hours. No one at the Archer Project doubts that some of their clients are responsible for anti-social behaviour in the city centre, and that some people feel threatened by this, but in their response to Sheffield Council, the organisation said there wasn’t enough in the PSPO proposal to convince them it would not merely be “punitive and performative”. Tim Renshaw says the police are aware of the need to support those who fall foul of the PSPO rather than simply displace the problem, adding that the PSPO would stand more chance of success if it was paired with a peer support scheme of people with lived experience of life on the streets. The chances of such a scheme being in place by the time the PSPO comes in next April seem slim.

Working in this industry isn’t for the faint-hearted. Renshaw says the people the project works with often display ambivalence towards questions of life and death. “People will say things like ‘If I die, no one will miss me,’ or ‘Dying would be better than living.’ That comes through loud and strong,” he says. But amidst this, there is also laughter and hope. “The city is full of people who have been in that place and who have managed to get away with the right support,” he says. “We never give up.”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.