There’s a handful of viable contenders for the dubious honour of being my favourite piece of Sheffield graffiti. The honest, open-hearted glee of “I LOVE THIS PUB” daubed by the front door of the Rutland Arms is one, the scribbling in Delicious Clam inspired by the Tribune (in my highly biased opinion) is another. While I’ve never spotted it myself, my housemate tells me there’s a set of drawings in the city centre portraying Sheffield as various kinds of eggs.

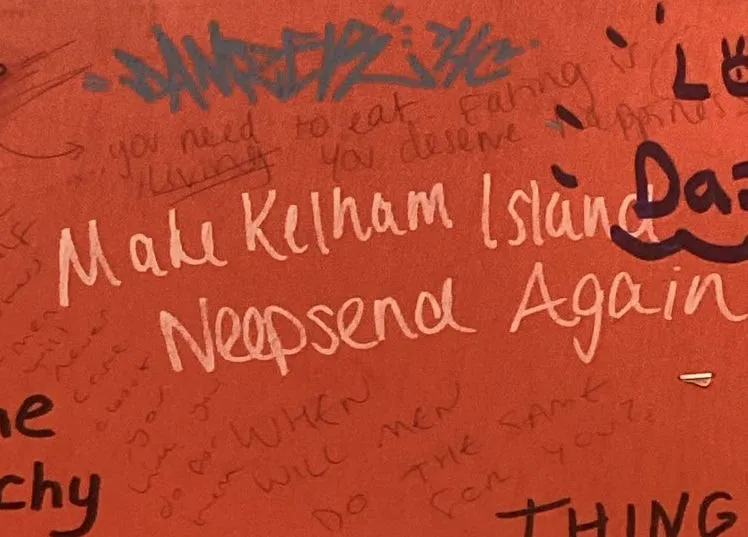

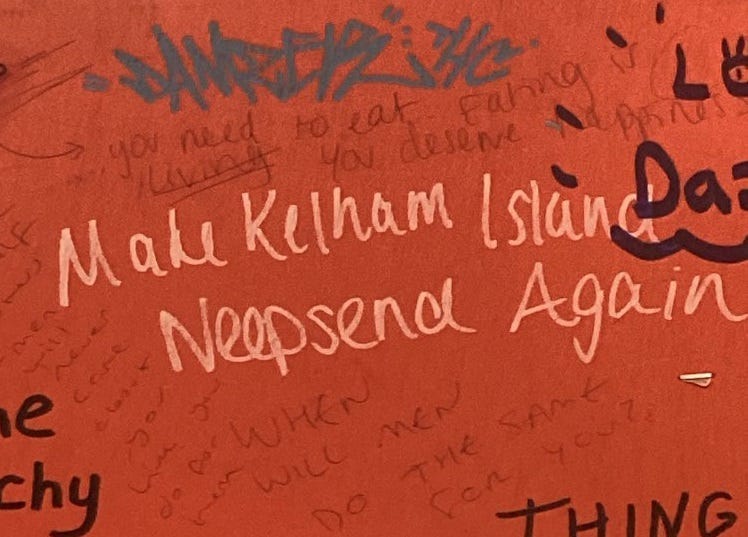

But the clear leader of the pack can be found in the toilets — where the best examples always are — of the bar-slash-venue-slash-club Sidney&Matilda. It’s a simple proclamation that, whether you agree with it or not, sums up its political message succinctly. It reads: Make Kelham Island Neepsend Again.

What this is gesturing at is the fact that there are really two Kelham Islands in Sheffield: Kelham Island the literal man-made island and “Kelham Island” the neighbourhood or, to put things more cynically, the branding exercise. In recent years, Kelham’s it-factor has risen so high that it overflowed and gushed into the surrounding area, abruptly annexing part of Neepsend. As one bar manager in this nu-Kelham told me, taxi drivers now sometimes gripe about customers who ask to be dropped off in Kelham Island, only to complain that they actually want to be on the other side of the river, forcing the driver to detour around new pedestrianised zones.

Where, you might ask, does this expansion end? Are we destined to see more and more parts of the city gerrymandered into Kelham Island? Until I, in my HMO in Nether Edge, am also a citizen of Kelham? Until, perhaps, the whole of the United Kingdom is one great Kelham Island?

It’s been just shy of a year since we last reported on Kelham Island and its rocketing ascent. Only two months later, the Sunday Times named it one of the best places to live in 2023 and argued it stood proudly “at the cutting edge of Sheffield’s recent revival”. In that first piece, Dan Hayes wondered what life was like for residents living on the precipice of this bold frontier, an area where the dominant industry has long been the manufacture of a good time, in one form or another. As the Arctic Monkeys sang, years before anyone would dream of opening a bar selling “drip-infused spirits” in this corner of the city, “it changes when the sun goes down”.

His article, based on visits in the crisp January daylight, questioned how well an area like this can sustain a life — a 24-hour, seven days a week, occasionally sober existence. Heading down on a Thursday evening in the optimistic early days of many people’s Dry January attempts, I wanted to find out what might come next for an up-and-coming area that has now, decisively, up and come. After all, there is no mistress in this world more fickle than “cool”.

My first port of call is a place conspicuously absent from the Sunday Times write-up, despite having won multiple awards, one that predates all this “industrial-chic” froth. Kelham Island Tavern is, a regular tells me, a “coffin-dodgers’ pub”, which clearly inspires fierce loyalty. A man perched on a stool tells me it’s been his local for the last 21 years, despite the fact he now lives 12 miles away in Stocksbridge. I’m told a couple regularly travel from Nottingham to drink here.

Matt Tanser, who has worked in the Tavern for 4 years and drunk in it for 14, says the ascent of Kelham Island was gradual until 2016, when some kind of dam seems to have broken. “They all just started popping up,” he says of the area’s newer, trendier additions. At first they were an incredibly welcome addition, pulling in new customers, some of whom inevitably found their way into the Tavern. “Everywhere started by opening full hours,” he says, “but now places don’t open up mid-week so it’s a bit dead Monday to Thursday.” He gets the sense that the Kelham Island wave has already crested. “I think it’s reached saturation point, you have to have something really special to succeed now.”

The Tavern’s customers, however, all of whom are older, suspect he’s being too pessimistic. Ollie, the regular from Stocksbridge, points out there’s “still plenty of land to build on” — and where there’s space, there’s space to grow. Gregory, a former Londoner who sits in the corner with a gorgeous Labrador and Cocker Spaniel mix called Frankie, says people have always been far too ready to call time on regenerating neighbourhoods. “When I was a boy, everyone would say every year ‘Covent Garden has peaked, Covent Garden has peaked’ but places don’t really peak, they just change into something else.” That said, he concedes the area can’t stay trendy forever. “Everything moves in cycles and it can all change very quickly. All it takes is for one particular landlord to change and people go off.”

Opinions differ on what could be the next Kelham Island, when the shine dulls completely. As Dan reported previously, developer Citu — who are responsible for almost all of the new homes on the island — are investing heavily in Attercliffe, having recently agreed to build 1,000 new homes. The area “could be huge,” Gregory says, although its “big chance was if HS2 was constructed and went through there”. Without a solid transport link, others suspect it might be too far out. Tanser, for his part, suspects the Wicker will be the next big thing, for the simple reason that it’s cheap. “Pitsmoor and Burngreave have quite lively communities,” Gregory notes, “despite the fact west Sheffielders behave like it’s Beirut.”

There is currently a pretty sharp line between Kelham Island and the neighbouring areas to its east — indeed there’s a sharp split across the city as a whole — and there are signs that resentment over this fact is already steeping. In 2019, Sheffield Council agreed the official boundaries of the Kelham Island and Neepsend Planning Area, the necessary first step towards creating a neighbourhood plan that will set agreed limits on future housing developments. Residents, as quoted in a council report at the time, had fought for the planning area because their home was “facing unprecedented change” from property developers keen to cash in, which they felt “threatens the social fabric of [their] community”. Having a neighbourhood plan might attach some much-needed reins to the racehorse, before it runs away with itself.

The lone voice against this idea, though it was approved anyway, was Cllr Mark Jones, who represents the adjacent Burngreave ward. In an email to the committee considering where to carve out the boundaries of this new neighbourhood, he wrote that he was struggling to understand how agreeing to designate Kelham Island as its own “autonomous zone” would amount to much more “than a mechanism to further stifle economic development of Burngreave”. The area’s future prosperity is, he argued, “reliant on developing all of the city, not just select areas by and through the exclusion of others”.

After finishing my half-pint at the Tavern, I decide to canvas opinions from the vanguard of the new, up-market Kelham, although I have to walk a fair distance along empty streets and past darkened windows to find someone to talk to. One of the few places open on a Thursday evening is Kelham Wine Bar on the very edge of the literal island, though it’s in the middle of the council-decreed neighbourhood. Aaron Melville, who has worked there for three years now, would frankly struggle to avoid talking to me, given we’re the only two people there.

“On Friday and Saturday, there’s no issues at all,” he says, but most places are struggling to crack the problem of mid-week trade, which will only get harder when Sheffield Council gets rid of the area’s remaining free parking. “We try to do stuff not a lot of people in Kelham are doing,” he adds, like ‘bottomless dining’, an evening answer to bottomless brunch, “but people are still not after it.” In common with Tanser from the Kelham Island Tavern, he suspects some kind of ceiling has been hit. “I don’t see it ever getting better, I can’t see what more you would do.” Already, he says, some of the businesses that were set up during the initial gold rush are starting to clear out.

Across the river in the Neepsend bit of Kelham, however, Jamie Woodgate is far more optimistic. He’s the second-ever manager of Neepsend Social Club, which opened in the summer of 2022 and is designed to look like a traditional working mens’ social club, complete with two darts boards in the back. Setting the question of whether it's a tiny bit gauche for somewhere that serves £10 poutine to brand itself this way aside, it boasts the first signs of life I’ve come across since leaving the Tavern, which I’m told is down to it being Drag Bingo night.

Woodgate is a cheerful graduate from a hospitality degree at Hallam and only took over the bar in April last year. Far from being over and done with, he insists Kelham Island has only continued to evolve in the months since. “This area is still developing, it’s not finished yet. I think it’s got another four or five years to go.” He gestures to the new housing developments that are popping up, which will hopefully give the bars a new semi-captive market. “In the next year or so, there should be a lot of people being airdropped in, so a lot of businesses are looking ahead.” It’ll be a much-needed shot in the arm given, as everyone I speak to keeps pointing out, rents are climbing in step with the area’s rising profile. “I used to work on Ecclesall Road and the rent killed everything,” Woodgate admits. “Since Covid-19, that area has really looked sorry for itself.”

As for how Kelham Island can evolve, it seems there are limits — or at least limits for now. He and I end up talking about the newest addition to the local scene, a cocktail bar called Dirty Mirror, which opened last summer and which Exposed magazine suggested reflected the new “classy” Kelham Island. He admits he was surprised when it arrived. “I don’t think you could have anything too glitzy or glam yet, it’s still Kelham Island, its history does hang on.”

The final stop on my tour is back on the physical island, another semi-recent addition called SALT. The bartender Lydia Rourke is also new to Kelham and admits that she finds it a bit strange. “It’s very different to anywhere else I have ever seen,” she says, casting about for a way to describe it. “It looks quite Grand Design-y.” Like other people, she’s noticed that students don’t tend to visit as much, clearly finding it too expensive for their tastes. While she’s not confident enough to speculate on how long the gravy train can keep chugging, she does point out that V or V, a restaurant which “used to be proper popular,” recently shut down because they couldn’t afford the rising rents.

The rent isn’t the only thing that’s been rising recently; what concerns Rourke a lot more is the river. Being so close to the Don puts Kelham Island in danger of flooding, which due to climate change is due to increase in the decades to come. The way she sees it, the floods are proof the areas around Sheffield’s major rivers are already over-developed. “It’s because they’re building on the areas that are usually flood plains, they’re not leaving any space for the water to run off,” she tells me. “It’s only a matter of time before it happens again.”

I step into SALT not only because the pickings of actually-open businesses are very slim but also because, like the write-ups in TimeOut and the Sunday Times, its arrival seems a sign that Kelham’s current success is more than just a flash in the pan. Unlike most of the new businesses that have sprouted here over the last few years, it is not a homegrown offering. SALT Sheffield is the company’s fifth UK location, which it snapped up not long after buying a brewery and two taprooms in London.

This wouldn’t be all that significant in, say, Manchester — which has acquired enough cultural cachet to pull in a Chanel fashion show — but Sheffield has historically struggled to attract much interest from outside of South Yorkshire. Despite living in Leeds for half a decade, I personally managed to make it to 28 without ever thinking much about the city at all. (No offence intended.) Even the editor who offered me a job here, who is Manchester-based and hyperbolically southern, sounded like he’d stumbled into giving a eulogy for a perfect stranger when he tried to sell me on moving. “Sheffield’s very environmental,” he told me, “They like… trees.”

Nothing about this, to be clear, is down to this city’s lack of charm. Instead, it’s down to a staunch refusal to market those charms, a near-pathological humility. After all, Sheffield’s main pitch for many years has been that it is the “outdoor city,” reducing the beauty and splendour of a national park right on our doorstep to an adjective most people would apply to seating. Imagine, for a second, if something like The Leadmill of the 1980s had popped up in Leeds — we’d never hear the end of it. It would have spawned a TV serial and myriad “view from the backstage” books written by sweaty-palmed hangers-on.

Even The Academy of Urbanism, which tipped Kelham Island as a hot new neighbourhood in 2019, pointed out that its regeneration is fairly unique because it had to be “slow-cooked” — there was “no quick influx of cash” from elsewhere, no major developers looking to secure a piece of the action. For all that many of the people I speak to shrug their shoulders when I ask why the area took off, with some suggesting it was simply good luck, its success is arguably the result of decades of conscious effort, led by Sheffield Council and beginning with the creation of the Kelham Island Museum in 1982. Kelham Island didn’t arrive out of nowhere, instead it was dragged into the zeitgeist.

The interest from developers like Citu or, more recently, Capital & Centric, which plans to spend hundreds of millions turning the derelict Cannon Brewery in Neepsend into 500 flats, is merely the fruits of that labour. But, having worked so long and so hard to “make Kelham happen,” there’s a danger that local politicians will be desperate to keep the party going at all costs. Only last month, the Competition and Markets Authority issued a warning to the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority about how far back it was bending to keep the Cannon Brewery scheme afloat, after it agreed in September to give Capital & Centric a £11.6 million grant to plug a “viability gap”.

Which is to say, while I’ll readily be called a NIMBY for this opinion, I can sympathise with the anxiety that would lead someone to want to turn back the clock, to Make Kelham Island Neepsend Again. As much as Sheffield has long deserved more attention from the rest of the UK than it receives, attention from large property developers can be something of a poisoned chalice.

This is not to say that Kelham Island is not a genuinely hip and happening place with many fun things to offer. I know plenty of movers and shakers who advocate so religiously for pre-drinks at Alder bar that the owner should be paying them commission. I’m just making the point that the thumb of financial capital always rests firmly on the scales of cultural capital, and most people who rush to designate this or that neighbourhood “cool” are trying to sell you something, usually a flat.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.