Our Spring offer won't be around for much longer! Grab three months of full Tribune membership for just £4.95 while it's still available.

By Jessica Bradley

It’s nearing the end of winter — Thursday 6 February — but it’s still very cold, so Abiah Higginbotham wraps up warm. She walks the 15 minutes to George Cavill’s Democratic Temperance Hotel on Queen Street from her home in an area called The Ponds, right where Pond Street Bus Station would be built a century later.

Sheffield’s streets are grimy and dirty in 1851, despite the fines hanging over the heads of any resident who doesn’t sweep the footpaths in front of their house twice weekly. Abiah passes the gas-lit lampposts and back-to-back houses and the watchmen, whose job is to keep the footpaths clear of anything that could be a fire hazard. She thinks about the evening ahead and expects to be the only woman there who didn’t have to argue with their husbands about handing over childcare duties for a few hours.

That said, all the women’s husbands are on good cutler wages — partly because the work is so hazardous, says Esme Cleall, senior lecturer in the history of the British Empire at the University of Sheffield. But that isn’t why Abiah married her husband — a spring cutler, which means he makes knives that involve spring steel, like penknives and pocket knives, by hand. Abiah was born in Leeds to a radical family; of course she was going to settle down with a fellow Chartist.

In recent years, Sheffield’s population has been rapidly expanding alongside industry, with more people moving closer to the factories, and the town has become a breeding ground for working-class radicalism.

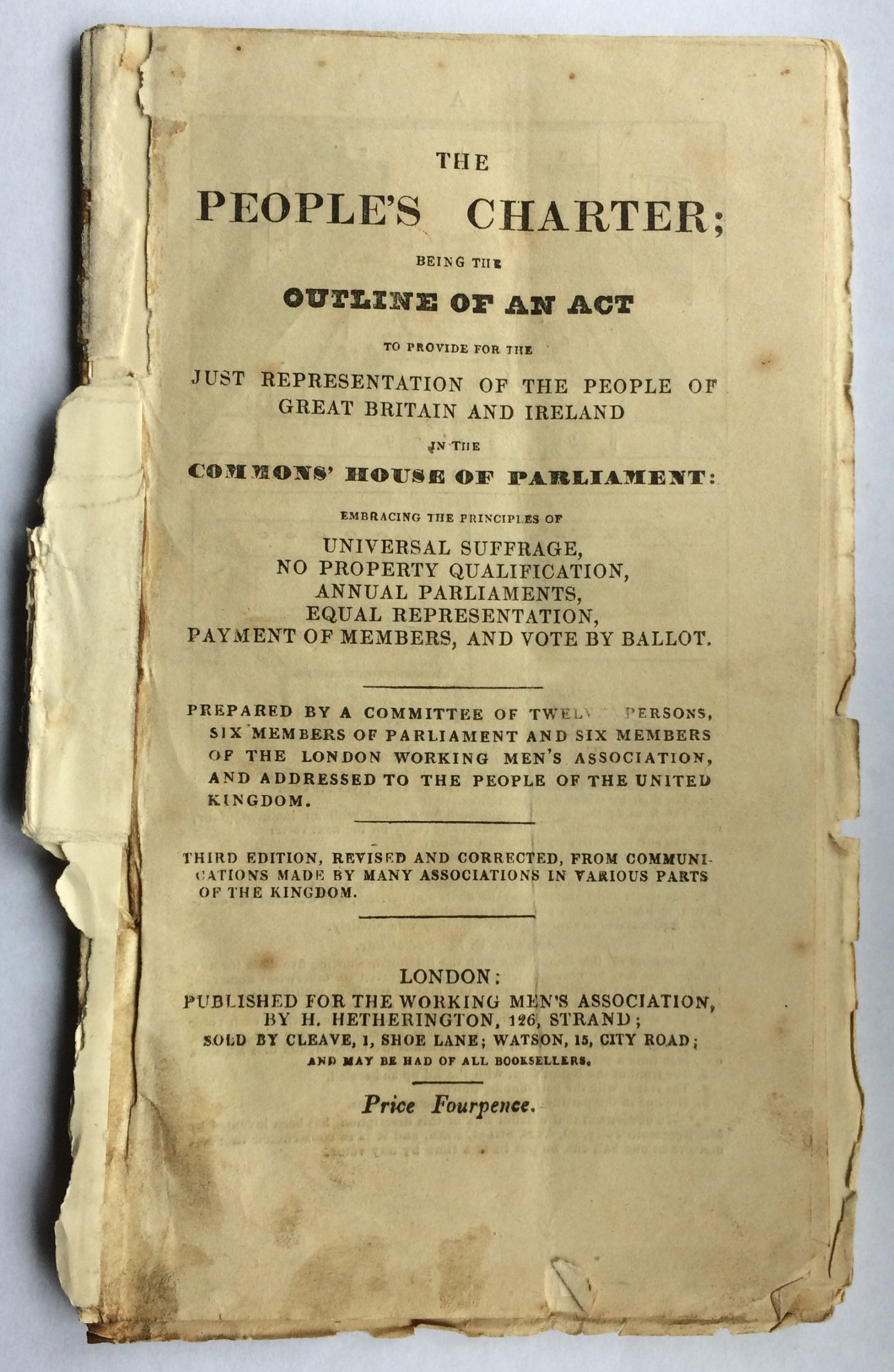

The Chartists have been campaigning for social, electoral and cultural change. It’s the first political movement initiated by the working class, but although Chartism has been bubbling for almost a decade now, it’s starting to burn out. “The upper working class get the vote in 1867, so 1851 is in the middle of Chartism. And then they split over tactics and fizzled out,” says Cleall. This includes men who owned their home or paid rent of £10 or more a year.

“Lots of women were involved in the Chartist movement — they spoke and petitioned”, Cleall says. “But they were abandoned.”

Women weren’t included in the People’s Charter, which called for six things, including voting rights for working men. “Although Chartists discussed giving women the vote, they — like typical men I suppose — said, ‘Let’s focus on men first’,” says Matthew Roberts, associate professor of modern British history at Sheffield Hallam University. “So, a lot of women in the early days tended to drift away from Chartism, partly because they didn’t see it as very welcoming, but also, it promised more than what it delivered, so people got disillusioned.”

The fact that women are being increasingly marginalised in the Chartist movement is one of the reasons Abiah is here tonight — and why she’s chair of the Women’s Rights Association (WRA).

A few months ago, when Anne Knight, a prominent campaigner, asked Isaac Ironside, socialist and Sheffield town councillor, for the names of Sheffield women who’d be interested in fighting for women’s rights, she was pushing against an open door. “Ironside must tell her there’s an interesting group in Sheffield who’d be interested in campaigning for women’s rights and puts her in touch with them,” Roberts says. Knight had encouraged the women to set up the first known women’s suffrage society — but they didn’t need much encouraging.

Abiah arrives early to the hotel — a striking building that, by this point, had established itself as the main Chartist venue in the town — and waits for the others to turn up, Eliza Rooke, Anne Thornhill, Eliza Bartholomew, Mary Brooke, Mary Hutton, Mary Whaley, Kate Ash, Eliza Cahill, Anne Higginbotham and Henrietta Holmshaw among them.

The “little band”, as Abiah once referred to it, first met three months ago. They’ve been working towards tonight, when the WRA unanimously adopts the first manifesto calling for female suffrage in Britain. The women address it to ‘the women of England — beloved sisters’ and say that they, “the women of the democracy of Sheffield”, have, for years, seen plans, systems and organisations put in place to improve people’s lives and, they argue, women should be included.

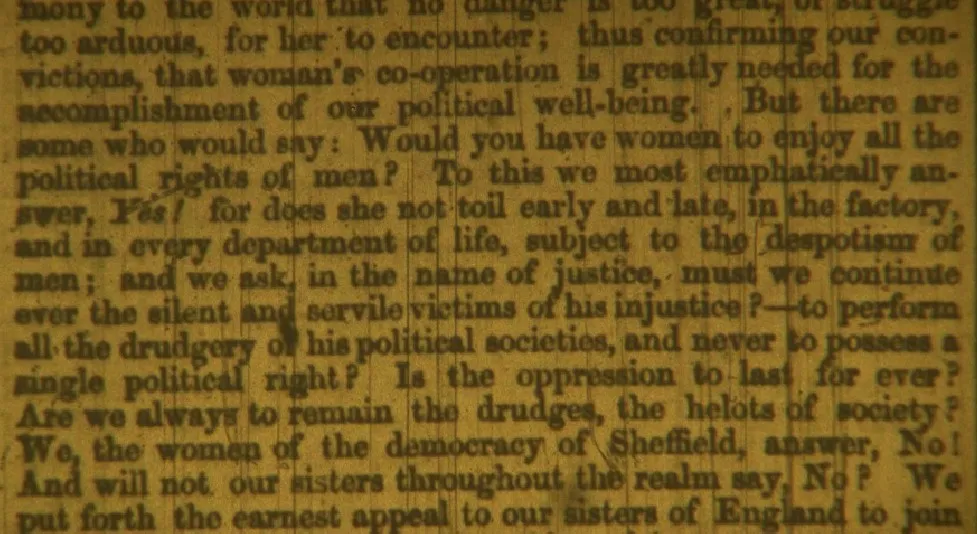

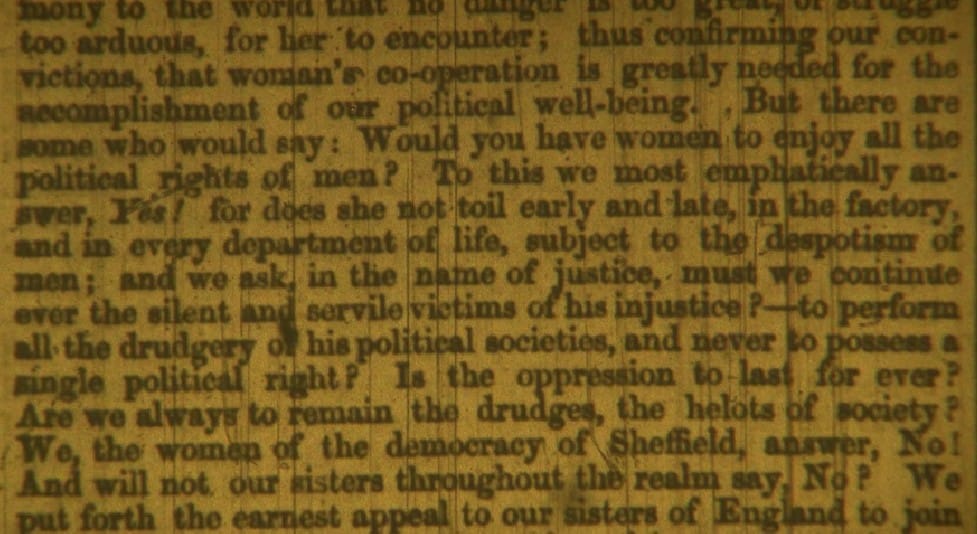

The petition goes on: “There are some who would say: would you have women to enjoy all the political rights of men? To this we most emphatically answer, yes! For does she not toil early and late in the factory, and in every department of life, subject to the despotism of men”. They ask: “Must we continue ever the silent and servile victims? Is the oppression to last for ever?” Three days later, Abiah sees the meeting reported in The Sheffield Free Press and Rotherham and Barnsley Advertiser.

The women meet every week at the Hall of Science on Rockingham Street. They celebrate the establishment of the WRA in April with a soiree and ball there, each wearing a white ribbon around their necks. Abiah gives a speech about “the industry and independence of women”, and everyone dances until midnight.

Abiah also meets weekly with her sister-in-law, Anne Higginbotham, at Abiah’s house, which she shares with her husband. “They thrashed out documents amongst themselves,” says Roberts. “And it makes it even more remarkable that many of the women couldn’t read or write themselves.”

One reason radicals meet is that someone who is literate — which, Roberts guesses, includes Abiah — can read the latest edition of the radical newspaper, The Northern Star, which reports on what the Chartists have been getting up to.

The WRA continue lobbying, writing to newspapers, hosting lectures — mostly in open-air places throughout the city — and encouraging other UK towns and cities to form their own groups. In one speech, the women take credit for inspiring “their sisters in Glasgow, Leeds, Edinburgh, and other towns”, and appoint someone to encourage the formation of other branches.

One of Sheffield’s two MPs, Whig John Parker, presents their petition in the House of Commons on 18 June 1851. The Earl of Carlisle — as one of the MPs for the West Riding of Yorkshire — presents it in the House of Lords in the same month, but it’s defeated.

Women’s suffrage isn’t the WRA’s only focus. They also write a letter in support of temperance, a growing movement to curb alcohol consumption that was especially popular in the north of England. “Temperance is quite important for these women,” says Roberts. “They want to see the amount of alcohol in society lessened because they see it ruining working-class lives. The women are also pacifists and don’t like wars fought in the name of British imperial aggression,” he says.

They write letters to Madam Kossuth, the wife of a Hungarian revolutionary, who was exiled along with her husband after the failure of the 1848 anti-monarchy revolutions throughout Europe, and to republican women in France. The radical Sheffield Free Press newspaper suggested that the Women's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848 inspired the establishment of the WRA. The women also campaign for a free press, as the government had put a ‘knowledge tax’ on newspapers that made them too expensive for the working class to afford. This led to years of campaigning and accusations that the government was hampering free speech among the working class.

But votes for women is the WRA’s overriding objective — and they conduct themselves unapologetically. “Unlike other women in radical movements, they really don’t pull punches,” Roberts says. He adds that, while a lot of women involved themselves in politics around this time, the WRA are unique in that they do so unapologetically.

“A lot of women excuse their presence, but Sheffield Chartist women don’t do any of that. They’re involved in discussions about whether women should be wearing stupid, impractical clothes, like corsets, to make their bodies attractive to men,” Roberts says. “The vote for women is the end in itself, but they’re already beginning to think, ‘how can we use the vote to get women’s issues talked about more?’ ”

Despite all these motivations, Sheffield was an unlikely place for the WRA movement.

You’d expect it to spring up somewhere that has lots of opportunities for women, Roberts says. But while women in neighbouring parts of the country are gaining some financial independence, Sheffield women aren’t being afforded the same opportunities. “In large parts of Lancashire and the West Riding of Yorkshire, there was factory employment women could go into,” Roberts says. These factories — including cotton and woollen mills — are mainly populated with women and children. And while they can be exploitative, Roberts says, they also allow women to earn their own income for the first time — and with it, independence.

These opportunities don’t exist in Sheffield, which is still concentrated with small, artisan metalware production. While large-scale industry comes 40 years later, that won’t bring many opportunities for women either, Roberts says. “A lot of the artisan, skilled men were earning a breadwinner’s wage, which meant that if they weren’t pissing it up the wall at the pub, they had enough to mean their wife didn’t have to go out to work,” he adds.

The town’s demographic isn’t exactly the most receptive to feminism, either. Gender historians often view Sheffield artisans as extremely misogynistic, because they saw women as a threat to their livelihood. They don’t want to employ them because they’d undercut men’s wages, Roberts says.

“What sort discussions did this lead to in marital homes? I suspect there were arguments. Some had large young families, yet women had the time to go out in the evening and write petitions in support of women, so there must have been some childcare going on,” Roberts says. “They might have been defying their husbands, although it could be the case that some men were being supportive.”

The WRA intends to become a national body, but this doesn’t happen. Despite its efforts, the group disappears from the historical record after its first year of life, possibly in part because the Democrat Party, which wasn’t very supportive of the WRA or women's rights, gained popularity around this time and was co-opted into the Liberal Party, which had traditional ideas of separate social roles for men and women

The last known reference to the WRA occurs during the July 1852 general election, when Abiah asks the candidates if they’ll support female suffrage. Liberal George Hadfield replies: “Wives should manage the inside of the house and husbands the outside affairs”.

Abiah dies in her 40s, in 1859. She’s buried in Hyde Park Cemetery in Doncaster.

Despite its short life, historians argue that the WRA was extremely significant in the development of the suffrage movement. “A lot of the national narrative about suffragettes is about [Emmeline] Pankhurst, but, like a lot of people protesting and campaigning, she’s standing on the shoulders of people who went before her and trailblazed,” Roberts says. And, importantly, the WRA also challenges the view that the suffragette movement was a “snooty middle-class metropolitan affair born in drawing rooms in Kensington and Mayfair,” says historian Amanda Vickery in a BBC documentary. “The whole campaign was born here, in Sheffield, in 1851.”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.