Data investigation: A year in the life of Sheffield's waste

202,000 tonnes. Roughly the equivalent of 17,000 double decker buses, 4,500 train carriages, or 20 Eiffel Towers. That rather mind-boggling number is the amount of waste Sheffield created last year.

Like most of us, I don’t spend much time thinking about where my rubbish actually ends up. I’ve got a pretty clear idea of what belongs in each bin (though I sometimes waver with those plasticky flyers you get — blue or black?) But once I put the bin out, I don’t think much more about it. But all this was set to change when I stumbled across the dataset which forensically details where it all goes. After days of sifting through the data for 2021/22 — it was pretty opaque at first — it finally revealed its secrets to me.

Green bin

Let’s start with the green bin, as it’s the most straightforward. You only get one of these if you request it (and pay £32 for it, plus £53 for a year’s collection) and it’s used for garden waste. Of the almost 12,000 tonnes of garden waste generated in the city, it all goes to one place — a Yorkshire Water site on the edge of Rotherham.

This seemed unlikely to me, but a look at the site in question on satellite view shows it to be correct. Next to the water treatment facility (left) you can see rows and rows of matter at different stages of being composted (right). This is “windrow composting”, where the waste is stacked in a row and occasionally turned over a 16-week timetable. The compost can then be used to grow other plants, and the cycle of life continues.

Presumably Yorkshire Water had the land going spare and spotted an opportunity to make a bit more cash on the side. So far, so sustainable.

Blue bin

The blue bin is for mixed paper and card. It’s the next bin up in the food chain — 15,000 tonnes — and contrary to my scepticism it seems most Sheffielders do know what to put in it. Less than 5% is contaminated by other waste, and that gets burned. We can follow those 687 tonnes further in their journey — but for now let’s focus on the good stuff.

After being sorted in Sheffield, according to the data it gets dispatched to North Wales. However, a look at that site (which was turning it into newspaper) shows that it’s closed down following a takeover. I put this to the council, who told me “Paper and card is sent to the council’s materials recycling facility in Beighton. It is then sorted and bailed into the various paper grades… Veolia then sell the sorted materials to various reprocessors depending on market prices.” So it seems the trail goes cold at that point.

Brown bin

Cans, glass, and plastic — so long as it’s a bottle. Any other plastic is to be sent to the black bin. It seems the brown bin confuses us residents more — with 1,500 tonnes wrongly ending up in this bin. That’s more or less twice the weight of Rio’s Christ the Redeemer statue.

This waste gets sorted in Alfreton, before being sent onto different facilities. Steel cans are recycled just next to the Don in Attercliffe. Aluminium cans and plastics (bottles only, but you knew that already) both get dispatched to Warrington. I have a quick chat with Chris Tarbuck, the site manager at Roydon Granulation, who tells me the PET plastic that’s created is used for applications like perspex and film by clients in both the UK and abroad.

As for the glass — well, therein lies a mystery. According to the council’s dataset that gets sent to a site in Doncaster. However, Kevin Needham, the Chief Operating Officer at URM Group (who own the site) is emphatic: “I can confirm that the site at Doncaster, or any other come to that, received no volumes of container glass from Sheffield in 2021 or 2022.” We asked Sheffield Council to explain where the glass actually goes after that, but at the time of going to print we don’t know anything other than where it first gets sorted. Updates to follow, should they get back to us at a later date.

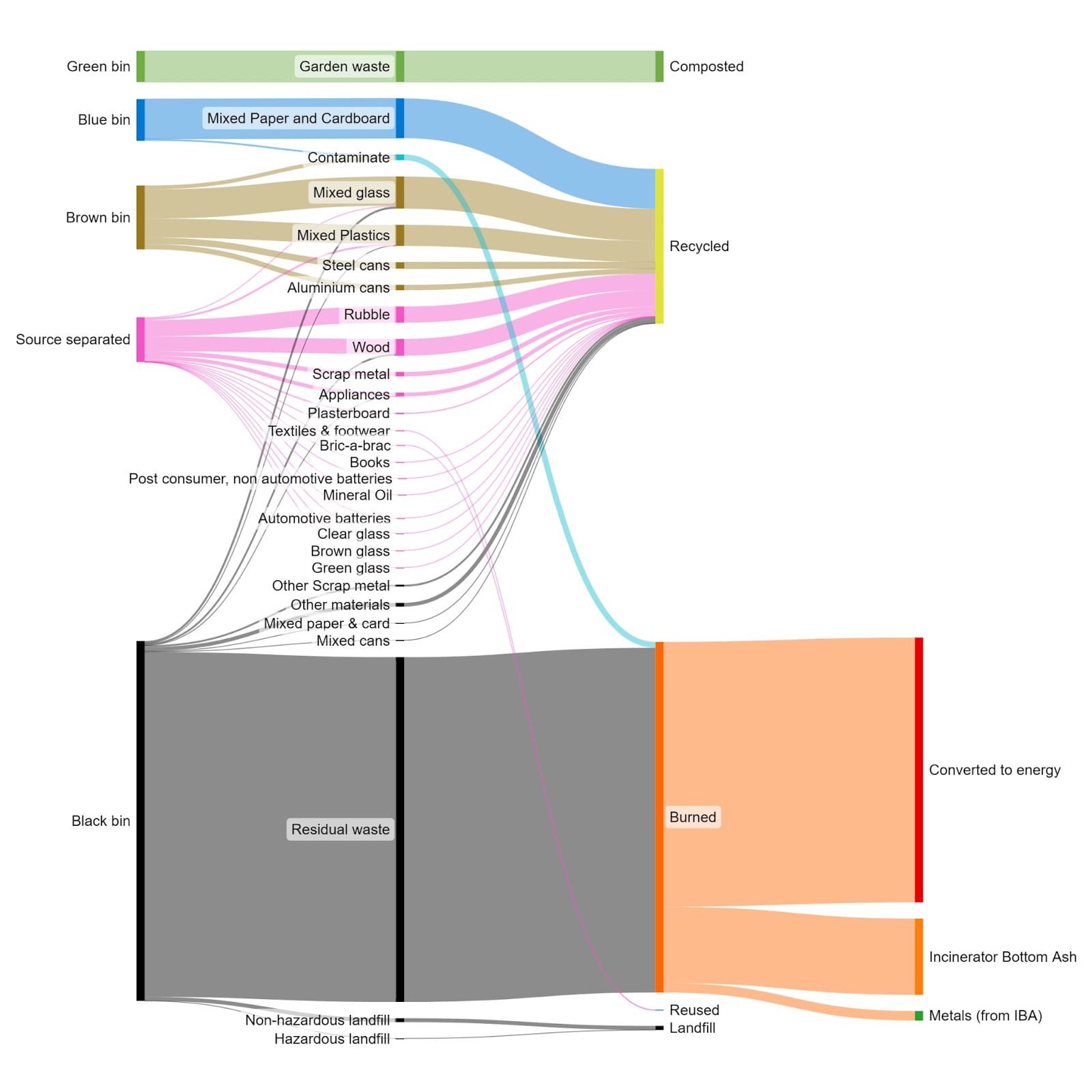

We’ll come onto the other two waste sources next, but this seems the right point to unveil the graph I’ve been working on over the last week. It shows the flows from all the different sources and where they end up. You can see from the brown and blue bins the amount of contaminate which ends up being burned, and that most of the contents end up in the right destination.

Source separated

A surprisingly large amount of Sheffield’s waste is sorted out at the source. Think bottle banks, clothes bins, and also industrial stuff where there’s an agreement with the council to take it away. Rubble and wood are the two main ones here. This category also includes the tiny, tiny amount of our waste (0.1%) that gets reused — clothes and bric-a-brac.

Black bin

One bin to rule them all. Take a long look at that chart, and you’ll see the black bin makes up significantly more than all the other categories put together. Of course, unlike many places, we have no food recycling, so all of that ends up in the black bin as well.

It’s not necessarily the end of the line for a piece of recyclable waste if it ends up in the black bin. You can see that small amounts are stripped off the top of the black bar, instead of meeting their doom in the incinerator. That includes 750 tonnes of glass, and 700 tonnes of wood.

Does that mean it doesn’t really matter which bin you chuck stuff in? Probably not, as it’s more likely to get contaminated if you chuck it in with old food and what have you. Nonetheless, if you’re still haunted by the memory of something you threw in the wrong bin, now is probably the time to allow yourself to imagine it probably got sorted out correctly anyway, as it quite possibly was.

A small amount of the waste also ends up in landfill — shipped over the border into Chesterfield. There’s only one destination for most of Sheffield’s waste though: the incinerator.

The site goes by the name “Energy Recovery Facility”, which Pollyanna-ishly accentuates the positive — energy is a product of the process (“Rubbish Burning Facility” has less of a nice ring to it). The rubbish that ends up here becomes the fuel source for a burning process that gets hotter than 850 degrees centigrade. That in turn creates both heated water for the city’s district heating network, and electricity which gets sold to the grid. The Town Hall, the Crucible, the Royal Hallamshire Hospital — all are kept warm, ultimately, by burning your rubbish.

Is this the right approach? Veolia, the operator, unsurprisingly think so, calling it “clean, green, sustainable energy…created from un-recyclable waste that would otherwise be sent to landfill.” However, as we’ve covered before in the Tribune, many disagree. Calling much of what ends up in our black bins “un-recyclable” is demonstrably false — in other local authorities many more types of plastic are recycled. Many councils collect other plastic packaging such as yoghurt pots, and some even collect “soft plastics” like wrappers, salad bags, and crisp packets.

Given this, it’s not surprising Sheffield lags when it comes to recycling. Only 34% of our waste ends up composted, reused, or recycled, versus a national average of 42%. We asked Sheffield Council whether they thought this was good enough. Councillor Joe Otten, Chair of the Waste and Street Scene, said: “In total during the year 21-22, the council sent less than 1% of waste to landfill. The approach we take means that we provide residents with a comprehensive service, which balances affordability, sustainability and environmental benefit.”

We also asked about whether they were looking to increase that number. We were told: “The council is always looking to improve our services. The Environment Act became law in November 2021, and whilst we await the exact detail of what changes will need to be made from government, we are working hard to prepare for these changes. In 2022 we ran a 12-week separate food waste recycling trial to help inform a future citywide roll out. We are expecting that the new legislation will lead to improvements to our kerbside recycling service for plastic as well as the introduction of weekly food waste collections.”

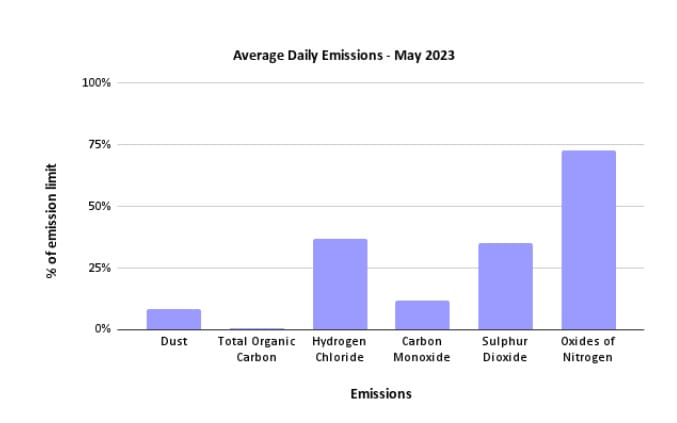

Of course, there are other by-products from burning waste. One is pollution in the form of various chemicals. There are strict limits, and Veolia stays within them, although nitrogen oxides pollution is normally closer to the limit (and is a pollutant we’re concerned with arising from traffic as well). But there’s a key pollutant that isn’t mentioned in the chart below: CO2.

It’s less relevant for those living near the site, but from the point of view of our atmosphere, that’s definitely not good news. The Environment Agency estimate that every tonne of waste burned releases 0.7 to 1.7 tonnes of CO2, meaning Sheffield’s waste burning is probably releasing around 150,000 tonnes of CO2 a year. For a city looking to go net zero, that is a big problem.

Pollutants aren’t all — when you burn stuff there’s ash left behind. At the right of the flow chart, you can see the 28,500 tonnes of “Incinerator Bottom Ash” (IBA) that fall out at the end of the process — equivalent to about a seventh of what we started with. This gets sent to a site in Hillsborough, operated by Blue Phoenix Group. According to their website: “The Phoenix is an extraordinary mythical creature. At the end of its life when just ashes remain, something magical happens. New life emerges out of something that seems lifeless. What we consider to be the end suddenly transforms into a new beginning.” This inspiring image is in fact a metaphor for turning the ash at the bottom of Sheffield’s incinerator into aggregate used for roads and other big infrastructure projects. (Some metal also gets sifted out of the IBA, which is recycled).

Waste not, want not

So there you have it — the true destination of what goes in your bins. From new roads to CO2 in the atmosphere, it certainly gets about.

On moving to Sheffield I was quite surprised by how limited the recycling options were, but over time I’ve got used to them. I shouldn’t though. Look at that chart one more time, comparing the “recycled”, “composted”, and “reused” bars to the “burned” and “landfill” bars. 32% to my mind is fairly pitiful — in countries like Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands over half the rubbish generated gets recycled or composted.

But the council is currently locked into its contract with Veolia until 2036. Incineration creates a tidy income stream and reduces energy costs. Will Sheffield’s newest incarnation of a Labour-Lib Dem-Green pact grasp the nettle and let us recycle more? Or will green aspirations go up in flames?

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.