Two lads smoking weed ask me why I’ve been loitering in Lowedges’ second-biggest shopping precinct for the last hour. They’ve got a point. There are only so many times you can walk around a quiet parade of shops in the middle of the day before arousing suspicion. When I tell them I’m a journalist doing a story about the cost of living crisis, they seem to believe me. Going further and insisting I wasn't a police officer was, in hindsight, a mistake.

As I chat to them in a roundabout way about inflation and energy costs, one idly grinds some of his stash in a plastic contraption he holds in the tips of his fingers like a piece of delicate machinery. But price rises are affecting them as much as anyone. “Everything going up man,” one says. “Everyday essentials, food, electricity. Everything.” When even the local weed guys are worried, you can be sure something big is going on.

It’s their turn to ask me about what I do. “Is your newspaper printed or on the internet,” asks one. When I tell him it’s just online he nods in agreement and commends me on my good sense. They don’t know the price of paper and newsprint has also skyrocketed in recent months, leaving traditional publishing companies’ profit margins mercilessly squeezed, but they figure it out themselves. It turns out I’ve met the smartest stoners in Sheffield.

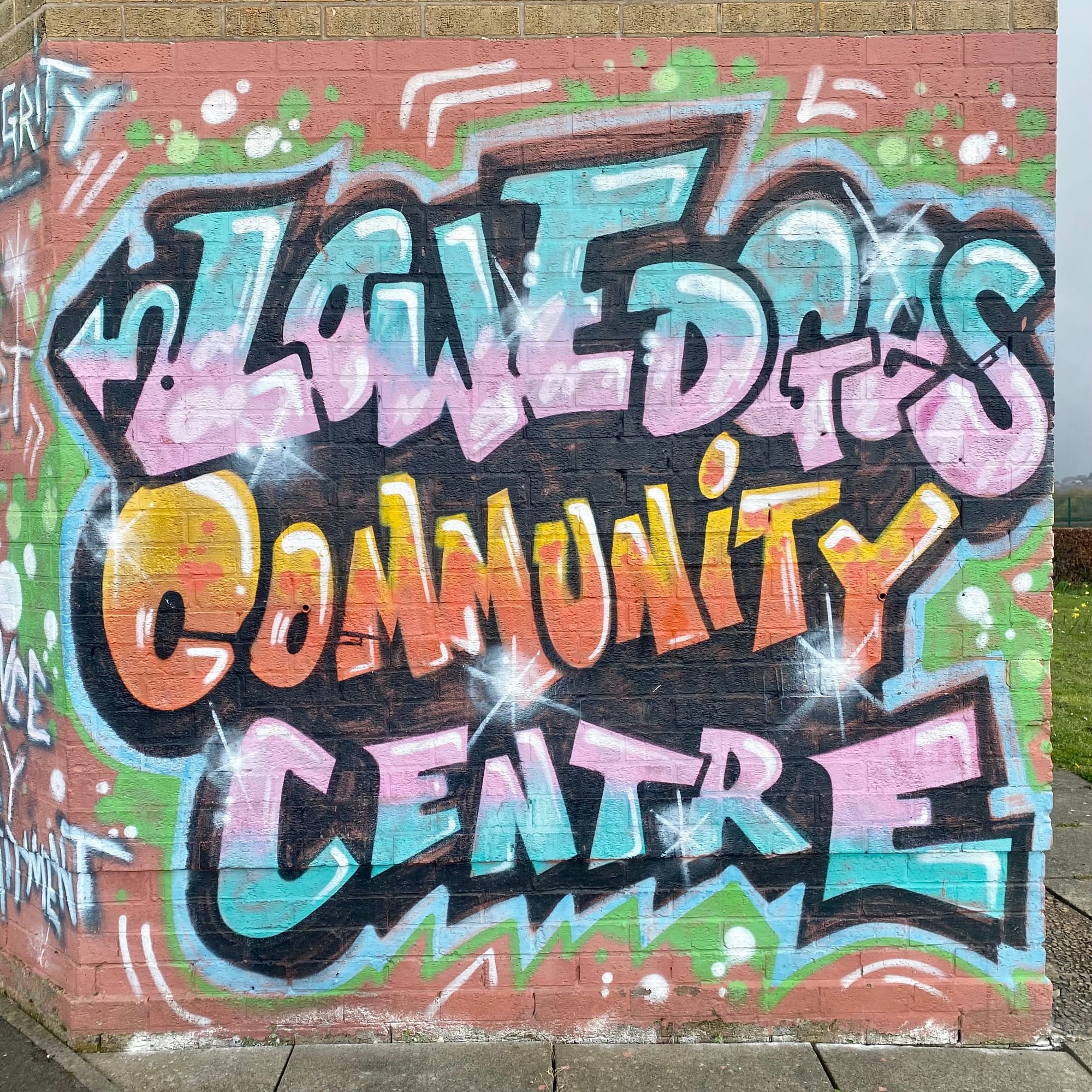

On the precinct stands a chippy, a hardware and household shop, two takeaways, a betting shop and a Premier store. A McColl’s shop is currently in the process of being turned into a Morrisons Local. Behind the shops the estate stretches out back towards Greenhill Parkway. Lowedges was built in the 1950s as part of the massive postwar council house expansion programme in Sheffield. Nearby Batemoor and Jordanthorpe followed a few years later.

The three estates are something of an anomaly in the city’s economic geography. While most of the social need in Sheffield tends to be concentrated in the north and east of the city, Lowedges, Batemoor and Jordanthorpe are known as a significant pocket of deprivation in the south. Just a few miles walk through Ecclesall Woods from the million-pound properties of Dore and Totley, sometimes travelling from one to the other feels like crossing into another country.

Behind the shops I catch up with single mum Sammy Taylor, 23, and her one-year-old son Clay. She’s not that keen to speak to me and definitely won’t have her photo taken, but eventually I persuade her I can be trusted. It strikes me that even at a time when so many people are feeling the pinch, there’s still a real stigma attached to talking about your financial circumstances.

Sammy isn’t at breaking point but she’s worried about the future. “Everything is going up,” she says. “Food, gas, electric. I’m just grateful I’m on a smart meter rather than a direct debit. You know what you are using and you're not just getting slammed with a bill every month.” Sammy is walking back to her nearby maisonette after buying some juice, pasta and sauce from the Premier store behind us. In her experience, it’s the bigger shops that are more of a problem. “I haven’t noticed it in the local shops yet,” she tells me. “But supermarkets just seem to be so expensive every week. I used to spend £60 but it’s been going up to £80 or £90.”

An older woman who doesn't want to give her name says her gas and electric bills will be going up by “half as much again” from April 1st: from around £800 to almost £1,200. As well as this, council tax is going up and she's worried about having to make major cutbacks. “Gas, electric, food prices: something is going to have to give,” she says. What will that be? “I’d sooner be warm and cut down on what I spend on groceries,” she says after a few seconds thought. “Still have food but cut down.”

The woman is 63, single, and lives on Universal Credit. She also has a six-hour a week job cleaning three mornings a week but for every pound she earns, the Universal Credit system takes 55p — more than half. “It’s crazy,” she tells me. “There isn’t much point in working but it’s what I have to do.” With the cleaning job she’s just £80 a month better off than she would have been if she was just on Universal Credit. “But with the price increases, that’ll be it. Gone.”

As well as the parade of shops, also based on the precinct is the Grace Food Bank. They serve the S8 and S17 postcodes but coordinator Jackie Butcher says the vast majority of their clients are from “the LBJ area” (Lowedges, Batemoor, Jordanthorpe). Jackie tells me most people they used to see had come because they had been sanctioned or they had their benefits stopped for some reason. Now most people are coming because they simply haven't got enough money. “No matter how you arrange the deckchairs on the Titanic, if there aren’t enough deckchairs it’s not going to stretch far enough,” she says. “People say I don’t get paid until tomorrow and I’ve not eaten since yesterday. I’ve got nothing.”

The problems have been getting worse for about six months, Jackie says, pointing to the government’s reversal of the £20 Universal Credit uplift and the end of furlough as a key moment. “They said the uplift was only temporary but people were really relying on it,” she says. “That happened at the same time the cost of living was going up and now fuel prices are going up as well. People just don't have enough money.”

A recent poverty and cost of living bulletin from Sheffield City Council said many people in the city were now facing cost increases that would significantly reduce their ability to afford essentials. On top of “dramatic” food price rises, energy bills are set to rise by 54% on an average bill. This includes significant increases in the daily standing charge that even people using the minimum amount of energy have to pay.

Household debt is also increasing and rents are going up, with lower-income households and private tenants most affected. At the same time, government-financed support schemes are also being withdrawn or cut back including debt and Universal Credit advice and housing and hardship support.

Having made friends with the weed smokers they kindly offer me a friendly piece of advice: maybe I might have more luck at “middle shops” — another, bigger precinct further up Lowedges Road. It’s a similar setup. Two convenience stores, a bakery, a hairdressers and a nail bar as well as several vacant units. Sat on one of the benches outside I find Dimitrios Athanassiadis, eating a cheese and onion pasty he’s just bought from Londis.

Dimitrios, 60, is wearing a scarf and warm clothes until south of his ankles: instead of shoes, he’s in flip flops and compression socks. As we talk, it transpires he’s just come out of hospital after a triple heart bypass operation. He wheezes when he talks and has to stop every so often to catch his breath. But he’s been told by his doctors that he should try to be active — hence why he’s out in the freezing cold temperatures walking around a shopping centre.

He says the cost of living is becoming a problem for everyone, but particularly those in places like Lowedges. “The fuel, the gas, the electricity, the food: all these things are becoming more expensive,” he tells me. Even the pasty he’s eating has gone up from £1.25 to £1.59 in the last year. “They say inflation is seven point something but I believe it is more than that,” he says. “I don't know what the government can do to stop it. It feels like the companies can do what they want.”

Dimitrios tells me his sick note lasts until May 3 but that he’s going to try to get an extension from his GP. Luckily his employer First Bus has been understanding so far, but the added pressure of thinking about money is not helping his recovery. “I worry every day,” he says. “A year ago we didn’t think about energy bills very much but from tomorrow it’s going to be very expensive. Me and my wife, we have to be careful how we control the expenses.”

Back at the food bank, Jackie Butcher tells me about how increasing energy costs are changing the way they think about donations. She says they used to get a lot of Fray Bentos pies which people liked. However, as these take 45 minutes to cook in an oven, microwave meals or pasta with sauces from a jar are probably better. “They’re not necessarily the healthiest or most nutritious things,” she tells me. “But we want things that take as little cooking as possible.” Some charities in the area are trying to help with fuel costs as well as food although funds are very limited.

But donations aren’t generally a problem. While being so close to places like Greenhill and Beauchief can make Lowedges’ plight seem particularly stark, Jackie says it also means they can count on a steady stream of donations from some of the better-off neighbourhoods nearby in a way that food banks on the Manor and Burngreave can’t. In the north and east of the city food banks are trying to cope with poverty but are surrounded by more poverty.

The coming crisis is going to affect everyone. Even previously comfortable households with two incomes will have to cut some luxuries from their budgets. But those who didn’t have any luxuries in the first place won’t have anywhere to go. And Jackie says the trap is catching more and more people all the time. “One of the things we see is how quickly people’s life circumstances can change,” she tells me. ”People say to us, six months ago I used to donate to food banks. I can’t believe I’m having to use one now. It’s really horrible.”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.