Kim McMaster, 53, has been involved with the Norfolk Park Tenants’ and Residents’ Association for almost her entire life. She now runs it alongside several mums, who grew up nearby and still live locally. It’s tucked away in Guildford Rise, nestled within several blocks of council flats, between Norfolk Park and the Arbourthorne estate. You would miss it if you didn’t know it was there.

Ensconced in the heart of the poorest community in Sheffield, the TARA is a lifesaver for many people. But, like several other groups in the area, its services have been cut as rising energy bills, dwindling budgets, and the after effects of the coronavirus pandemic take hold.

Just three years ago — they were cut during the pandemic, and never returned — you could have gone there for a coffee morning for senior citizens, a group for people whose second language is English, a homework club, a weekly youth club for children aged between six and 16, drop-in help sessions and a food bank. Now all that remains is the food bank (which is used by nearly 100 people and for which demand has nearly doubled in the last year) and a kids’ group at the local church. Kim says they can’t even afford to keep TARA open all week because of the skyrocketing heating bills.

Sadly, the TARA’s shrinking services aren’t an exception, hewing to a pattern of decline in the area. Kim tells me there used to be a whole row of shops on Park Grange Road, including a post office, butchers, a freezer shop, Co-op and a fish and chip shop. Now, empty stores covered in graffiti stand in their place.

Inequality in the UK is like water must be to fish — so omnipresent, such a fixed part of our daily lives, that most of us don’t even notice it’s there. According to the GINI coefficient, an index which measures income inequality, the UK has the dubious honour of having some of the highest levels of inequality in Europe. Similarly, according to the Equality Trust, between 2020 and 2022 alone, billionaire wealth increased by almost £150 billion. Meanwhile, 3.9 million children are living in poverty, more and more of us are forced to use food banks and 6.7 million households struggle to heat their homes.

These contrasts feel so dramatic that they’re difficult to wrap my brain round — they don’t quite feel real. So recently, spurred by the way the cost of living crisis seems to be decimating some of our poorest communities, I decided to investigate inequality on my own doorstep.

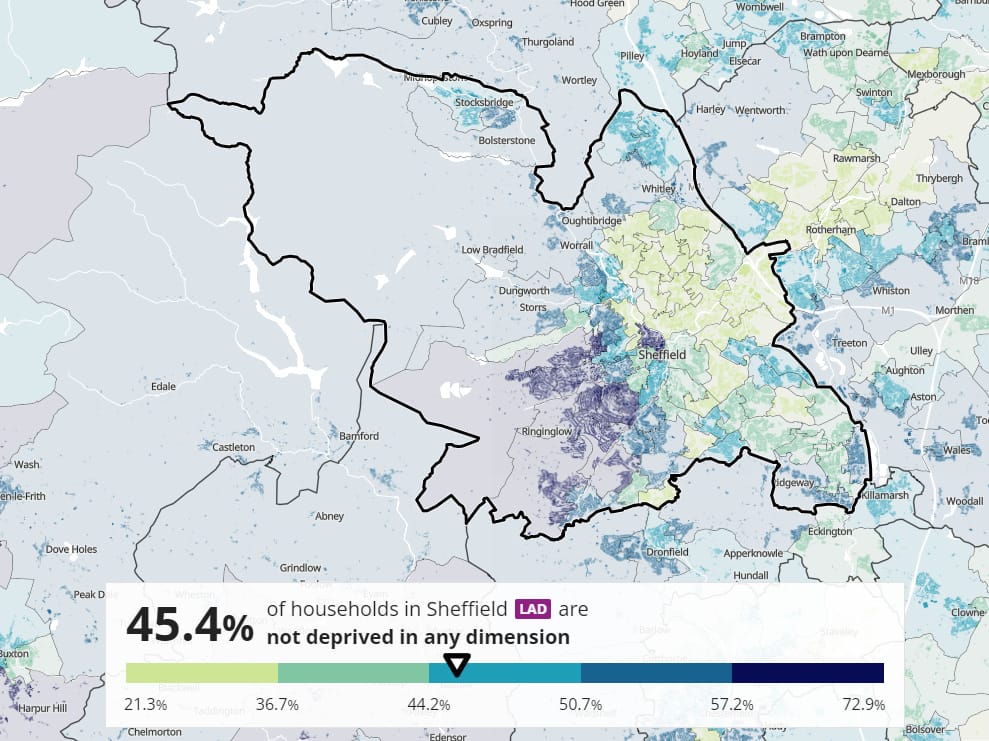

According to the 2021 census, across England and Wales, 48% of households are deprived in at least one of four ways.

These ways are listed as the following:

- No one has five or more passes at the GCSE level or equivalent and no 16 to 18-year-old is in full-time education.

- Any non-full-time student is unemployed or long-term sick.

- The accommodation is either overcrowded (it has one room or bedroom too few for the number of occupants), is in a shared dwelling, or has no central heating.

- Any member has general health that is “bad” or “very bad” or has a long-term health problem.

Sheffield has a city-wide average of 55% of households which would fall into one of these categories — not too different from Leeds, a similar city in size and demographic to this one, where 52% of households register in one deprivation area.

Leeds may have similar levels of inequality, but there’s one key difference: unlike Sheffield, the poorest neighbourhoods are interspersed throughout the city. In Sheffield, the line separating rich and poor is much more stark, running like a border from north to south down the centre of the city. This line separates Sheffield into two halves: a more prosperous west and a much poorer east. I resolved to spend some time in this city’s two worlds and report back — I’d begin in the most deprived neighbourhood in Sheffield, Park and Arbourthorne, before visiting the most affluent western neighbourhood, Greystones and Ecclesall.

Figures from the census show that almost three quarters of the households in Park and Arbourthorne are deprived in at least one of the four ways: education, employment, housing or health. This is well above the city-wide average and far worse than many of the richer areas, which are all located in the west.

I start my walk at Springs Leisure Centre on East Bank Road, where a group of mums are complaining about the cost of heating their homes. The cost of living crisis has hit people in Arbourthorne hard, and they have been forced to make difficult decisions as they cut back on their spending. They have just dropped their kids off for swimming lessons at the local pool and tell me they find it difficult to get any classes at all due to the high demand. Demand is one thing, but the pool’s size doesn’t exactly help — at just 20 metres long and four lanes wide, it’s hard to imagine it accommodating a substantial number of pupils comfortably. While sporting facilities for children and young people are lacklustre, youth clubs have also closed down in the area.

Derek, 86, who has lived in Arbourthorne all his life and now helps at a local residents’ association, tells me he used to run a kids’ club at Arbourthorne Social Centre on East Bank Road. It sounds lovely: They welcomed kids of all ages up to 16 into the centre, where a variety of games, crafts and other activities were on offer. But it wasn’t to last. During the coronavirus pandemic and following some threatening verbal abuse from a group of teenagers, Derek closed it down.

The lack of adequate local facilities is a recurring theme as I wander round the neighbourhood. Many social clubs and centres are on their last legs, and the local bank and post office have both closed down in recent years — “It doesn’t exactly send a signal that this is a place to invest in, does it?” one resident says. Perhaps not.

The Department for Education figures tell a similar story to the one I’ve heard from locals: Sheffield City Council spent £5.3 million on services for young people in 2021-22. This might sound like a lot, but it’s a substantial decrease from the £7.8 million assigned in 2015-16. Sheffield Futures, which ran many of the council’s youth services until its contract was not renewed in 2020, received £3.6 million in its final full financial year of the contract. In 2010, its budget was £8 million, slashed to £4.6 million within three years.

As I turn up Northern Avenue and walk towards the central collection of shops at the intersection of Cawdor Road, on either side, the streets are lined with cookie-cutter council houses, each rendered from the same frame. I know there’s a local litter picking group, but they seem to be fighting a losing battle: the gennels are strewn with crisp packets and Coke cans, while communal areas are overgrown and many of the shops look like they have been closed for some time.

At the Punchbowl Pub on Hurlfield Road, the car park is empty. Inside, a few stragglers watch football on large-screen TVs. Kirsty, a 47-year-old single mum of a teenage girl, says she’s struggling to make ends meet. “Life is hard,” she tells me. She says it’s getting more expensive to simply survive, explaining that she would like to earn more money but has experienced mental health problems, something else provision has been cut for in recent years in Sheffield.

Another local man I talk to tells me about how much he enjoyed his swimming classes as a child and points out he’d be unlikely to have that experience, growing up round here now. The lack of facilities for young people might not sound like a huge problem: boredom isn’t exactly deadly, is it? But that lack might have a knock-on effect. A row of new-build houses on East Bank Road had several windows smashed in, which Kirsty says is due to kids turning to petty crime. Wandering down to see the damage for myself, I briefly speak to a construction worker who says it happened months ago. He tells me the council and police have been informed, but nothing has been done about it.

In Greystones and Ecclesall, the picture couldn’t be more different. As I stroll up Ecclesall Road South, a group of students power past me, ducking into a packed local pub. Further up the hill, at a local cafe, there’s no spare tables — people tuck into late afternoon coffees and pastries. There’s a buzziness, a busy-ness here that was entirely absent in Arbourthorne. This isn’t necessarily surprising. Here, just 35% of households are deprived in one or more of the four dimensions. The hum of activity — presumably a result of the higher levels of disposable income being funnelled into local businesses — doesn’t relent as I make my tour of the neighbourhood. From Endcliffe Park to myriad coffee shops and restaurants along Ecclesall Road; from tennis, rugby and football clubs to local community centres; from easy access into the city centre to walking distance from the Peak District, there is everything and more at people’s fingertips. I’ve read the term “postcode lottery” before, who hasn’t? But the implications of the term have never felt so vivid.

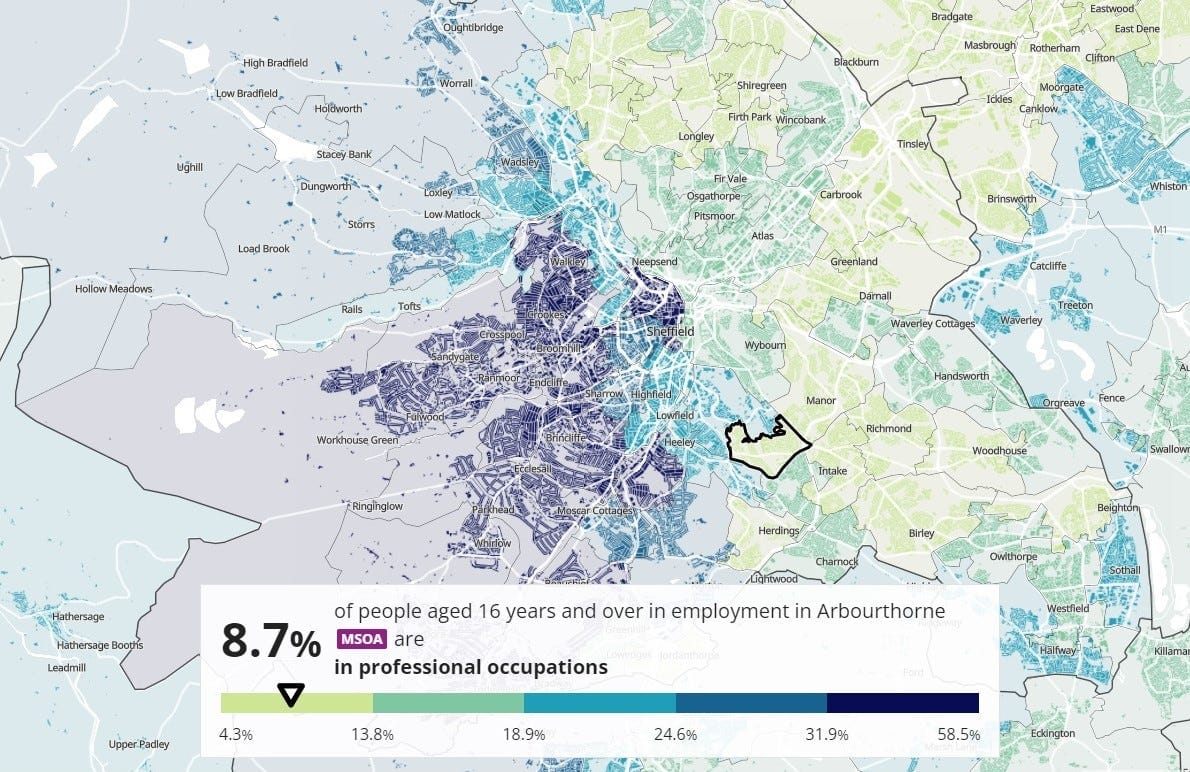

More census figures just released show 45% of over-16-year-olds in Greystones and Ecclesall work in a professional occupation, such as teaching, the finance and technology sectors, or a professional NHS job. It is the second-highest figure in Sheffield behind Lodge Moor. For Park and Arbourthorne, this falls to just 9%, the second-lowest figure in the city.

Andy, 49, is an oil painter who has lived in the area for 26 years after moving up from London. He tells me he was attracted to the area because of the boutique coffee shops, pubs and restaurants all along Ecclesall Road. Like many of his friends, he moved in his twenties. He then met his wife and started a family together, complete with their dog, Norman.

Andy says the area attracts higher earners because of the many students that move there for university. The Endcliffe-Ranmoor student village is the biggest in the city with 4,500 students living there. The students graduate, the graduates become families, and the children then grow up in an affluent area with plenty to keep them busy. Throughout it all, there is no need to move outside the “S11 bubble”.

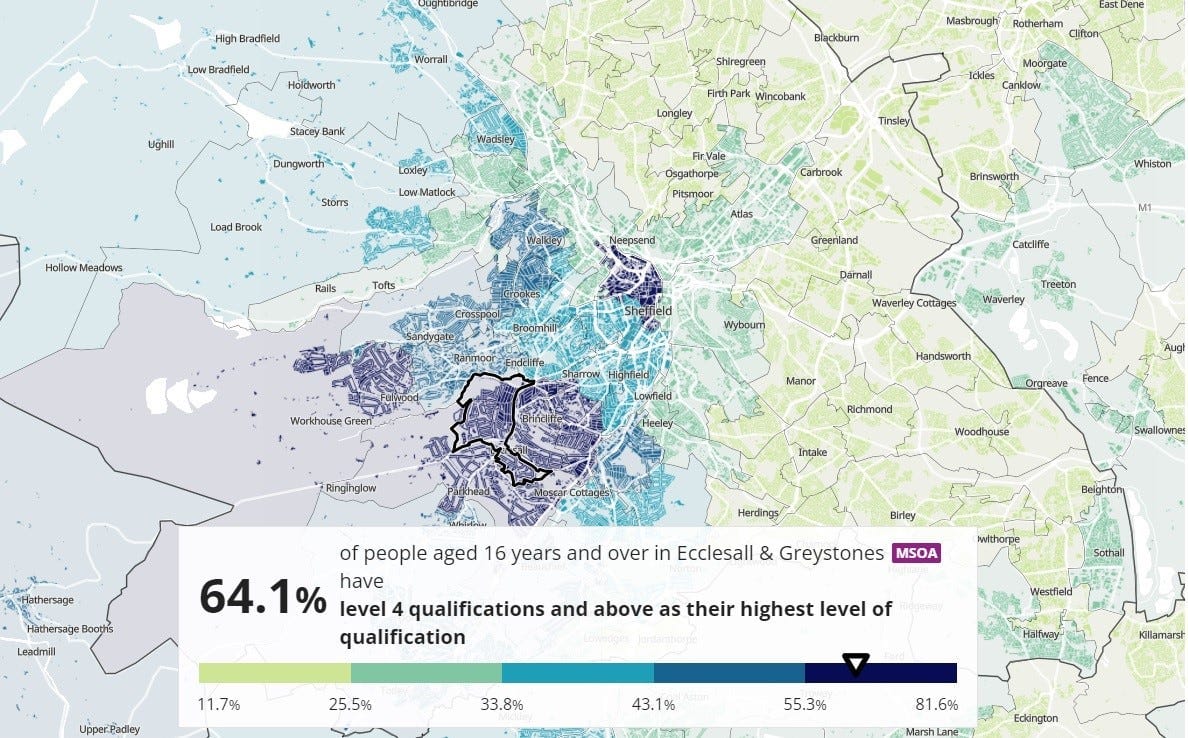

And why would they move away, especially if they wanted kids? After all, there isn’t just a disparity between levels of deprivation, but also a huge gap in children’s education. Just 16% of over-16s in Park and Arbourthorne hold a level four or above qualification — equivalent to an undergraduate degree, higher national diploma or higher national certificate. After Parson Cross, it is the second-lowest figure in Sheffield and lags well behind the 64% of over-16-year-olds that have a level four qualification in Ecclesall and Greystones — the highest in the city.

As I delve deeper into the differences between these two places, it becomes clear how essential the start children receive is to an area’s affluence. Park and Arbourthorne councillor Nabeela Mowlana grew up in the neighbourhood and attended Springs Academy. She insists the opportunities she received at school are not available to children today.

What she remembers from her school days is a steady pulse of support: teachers personally driving her to university open days, helping her with her studies and encouraging her to partake in extra-curricular activities, like politics. So what’s changed? “Teachers don’t have that capacity anymore,” she says.

Nabeela was the last year to study A-levels at Springs Academy, with the sixth form closed down entirely just a year later. There are now 11 state schools with sixth forms in the city. Seven of them are firmly in the more affluent western areas.

There is a far greater eagerness to achieve academically in these schools, Nabeela says. Subjects such as economics, philosophy and politics are all encouraged, and many children are expected to go to university. “It is a completely different world,” she tells me. Poor behaviour is also treated very differently. In schools in the west, Nabeela says, if a student behaves badly, they are not just reprimanded but rehabilitated. In places like Arbourthorne, schools seem to take a punitive approach, with suspensions and exclusions used more regularly.

In the 2020-21 school year, Department for Education figures show Springs Academy permanently excluded four children. Silverdale and High Storrs excluded none. Meanwhile, it also handed out 181 suspensions, more than double Silverdale and High Storrs combined. And this is all while schooling around 600 fewer children.

So what’s to be done? “Huge investment is needed to reverse the accident of birth and your life chances,” she concludes. But as the government prepares for a fresh era of austerity, investment of the kind that Nabeela says is needed doesn’t seem likely. Which is upsetting, because the coronavirus pandemic had a major impact on children’s development, potentially worsening the inequality already present in the system. The TARA had nine laptops to help parents across Norfolk Park and Arbourthorne who were struggling to homeschool their children during lockdown — one per household. It was not nearly enough. “When the world went online, a lot of parents were left behind,” Kim says.

Children were expected to sign in to their classes online, but one mum had no device for her children to use. She tells me it took six months for Norfolk Primary School to start handing out printed materials. “How can one per household be enough when you have three children, each a different age, year group and lesson? It’s madness,” she says.

By this point, I’m dispirited and in desperate need of a pint. On heading to the Greystones pub on Greystones Road, I meet another local resident. Phillip, 72, who now lives in Ecclesall, grew up on Arbourthorne estate. He has lived in S11 for several decades, moving earlier in his adult life to set up a tailoring business on Ecclesall Road.

He “escaped” Arbourthorne because he had the opportunity to travel in his younger years. It meant his eyes were lifted above the horizon to what was possible outside of the estate, and when he returned to Sheffield, he knew it wouldn’t be to where he grew up.

“I was the lucky one,” he says. “It’s not that people aren’t working hard or aren’t smart enough, but when you’re in poverty, it’s very difficult to get out.” That difficulty feels all too evident when I speak to residents in Arbourthorne. Most rent a social housing property. Many have little to no savings, are on pre-payment meters for their heating and energy, and rarely feel “secure” in their situation. “No one is living, they are all just surviving,” Kirsty at the Punchbowl tells me.

She tells me that she has had to move houses on several occasions at short notice. But she’s one of the lucky ones: she now lives in private rented accommodation, something she notes most people cannot afford to do. After all, they would need the first month’s rent and a security bond — which is usually worth five weeks’ rent — before they have even set foot in the property. “That’s £1,600 you have to find before you’ve even furnished it. It’s impossible.”

Phillip remembers Arbourthorne being a “nice, tidy estate” when he lived there as a child. But when social housing changed from being a leg up to being a housing of last resort, this had the effect of concentrating deprivation there. This decline has intensified differences which already existed in a “self-perpetuating” circle, where children take after their parents in both areas. As a result the wealthy get wealthier, and the poor get poorer.

He tells me the east of the city has always been the working class side due to Sheffield’s westerly winds. The rich bought the houses on the west, knowing the wind would blow the smoke to the east, where the steel factory workers were packed into tight terraced housing.

A study from the Spatial Economics Research Centre by Stephan Heblich, Alex Trew and Yanos Zylberberg in 2017 suggests he’s right. The paper used mathematical modelling to recreate western cities in 1880, during the industrial revolution. Following the movement of the air, it claims historic pollution “explains up to 20% of the observed neighbourhood segregation, whether captured by the shares of blue-collar workers and employees, house prices or official deprivation indices”.

Sheffield is no anomaly to this pattern, with many of the steelworks and factories located in the east of the city, while leafy suburbs with much cleaner air were situated in the west, sheltered from the polluted eastern skies.

This history plays into the “segregation” we see between Arbourthorne and Ecclesall today — and it is why many people like Phillip longed to escape the more deprived eastern estates for more affluent western neighbourhoods.

Sadly, Arbourthorne has declined over the last decade. “No one wants to look at the area they grew up in and think ‘it’s all gone to shit’,” Nabeela says. The area faces a lot of challenges, including high crime rates, extreme poverty and lower educational attainment.

But without adequate investment, there will be little progress. Only through consistent and serious spending, Nabeela says, can there be a nearby sixth form, or upgraded sports facilities, or local youth clubs, or thriving high street shops, or community events.

Nabeela — like many of the residents and councillors I spoke with — is confident in Arbourthorne’s potential and is extremely proud of where she grew up and now lives. But she also knows that for the area to enjoy a brighter future, we can’t avoid the obvious: change is needed. Not next month, or next year, but now.