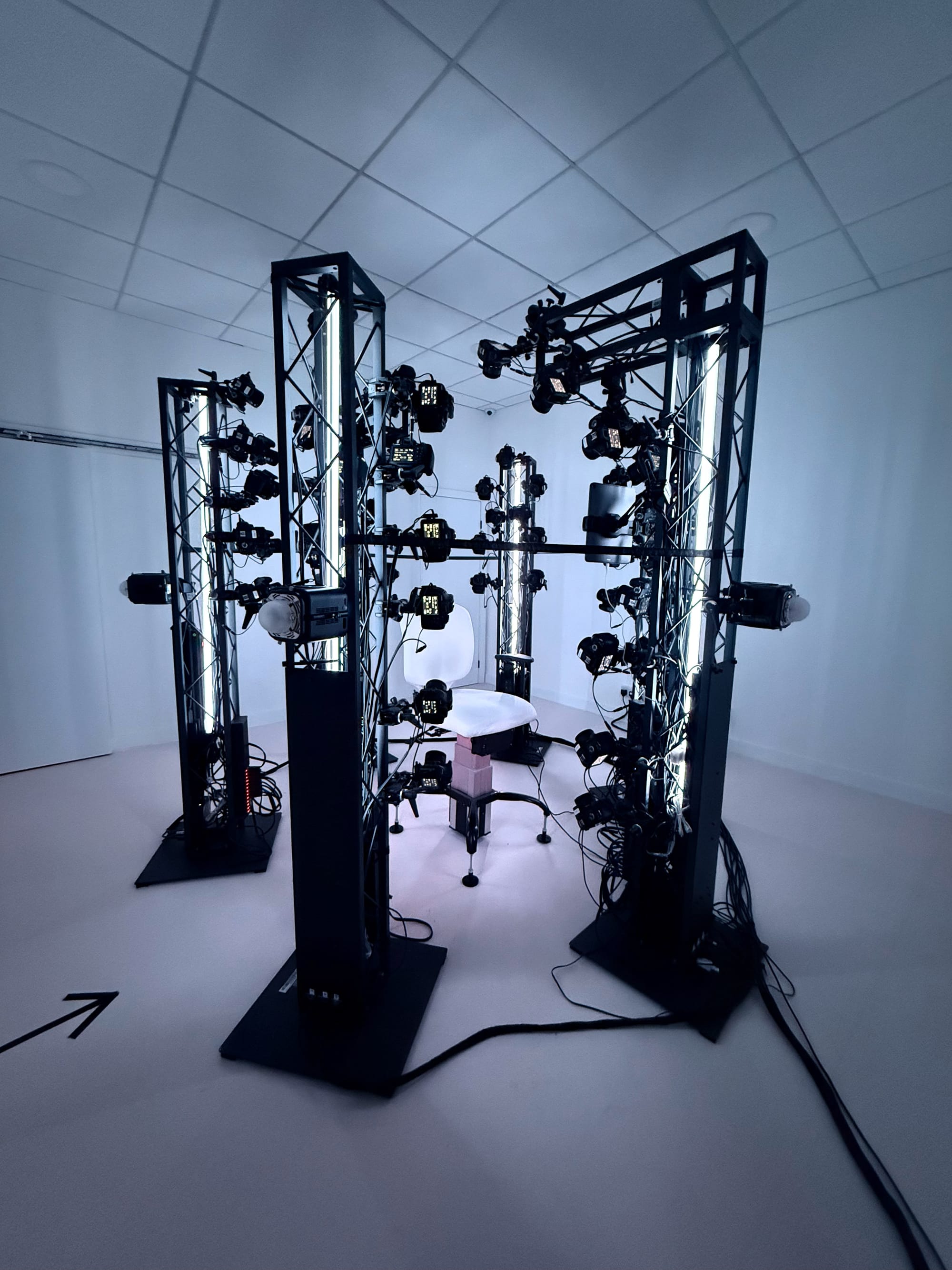

My fingers grip the edge of the seat, and my body sits stiff to attention. 71 ultra-high resolution cameras are trained on me from all directions. Every tiny crinkle, ridge and bump of my face is exposed to their glare.

Five minutes earlier. I step into the Sapiens shop from Orchard Square to be checked in. Several staff tend to me, guiding me past the pink screens telling me my rights, into a room where a supervisor places an iPad into my hands. I skim the waiver form — having already read through everything on the website days before — but I still feel some unease about certain clauses. ‘I waive any rights, claims, or interest I may have to control the use of my likeness’. ‘I voluntarily and knowingly waive any statutory right or prohibition relating to the Biometric Data’.

I’m taken into a private dressing room, where I’m coddled and pampered with compliments on my cardigan, my hair, my face. A woman passes me a grey tank top from a pile neatly folded on a shelf to change into. She puts my hair up into a wig cap and gently tucks my flyaways in with the end of a comb. My face is all that matters. The rest is immaterial.

Then it’s time. A door I hadn’t noticed earlier slides open, I walk to the seat, and the decision is final. ‘Lean back a little’, an assistant tells me. Seventy-one shutters click in unison, and a millisecond later my face no longer belongs to me.

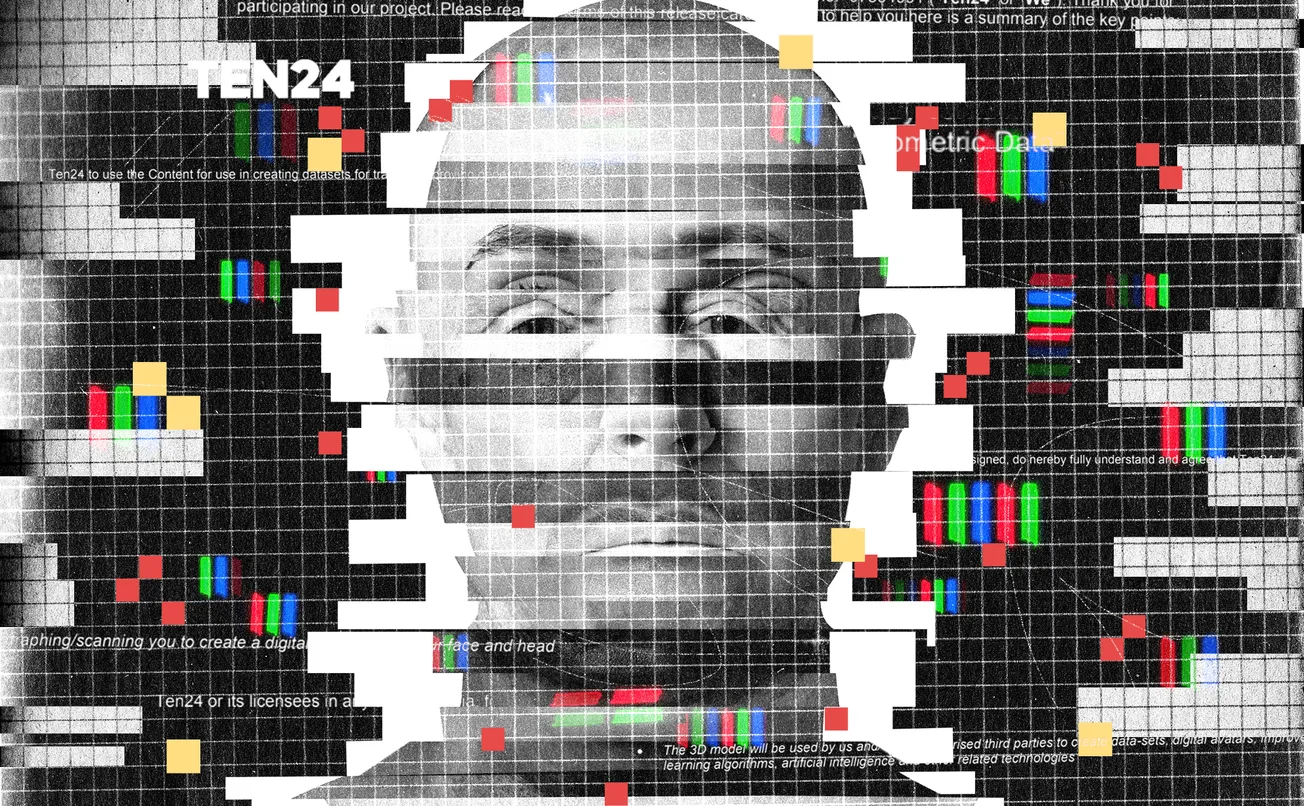

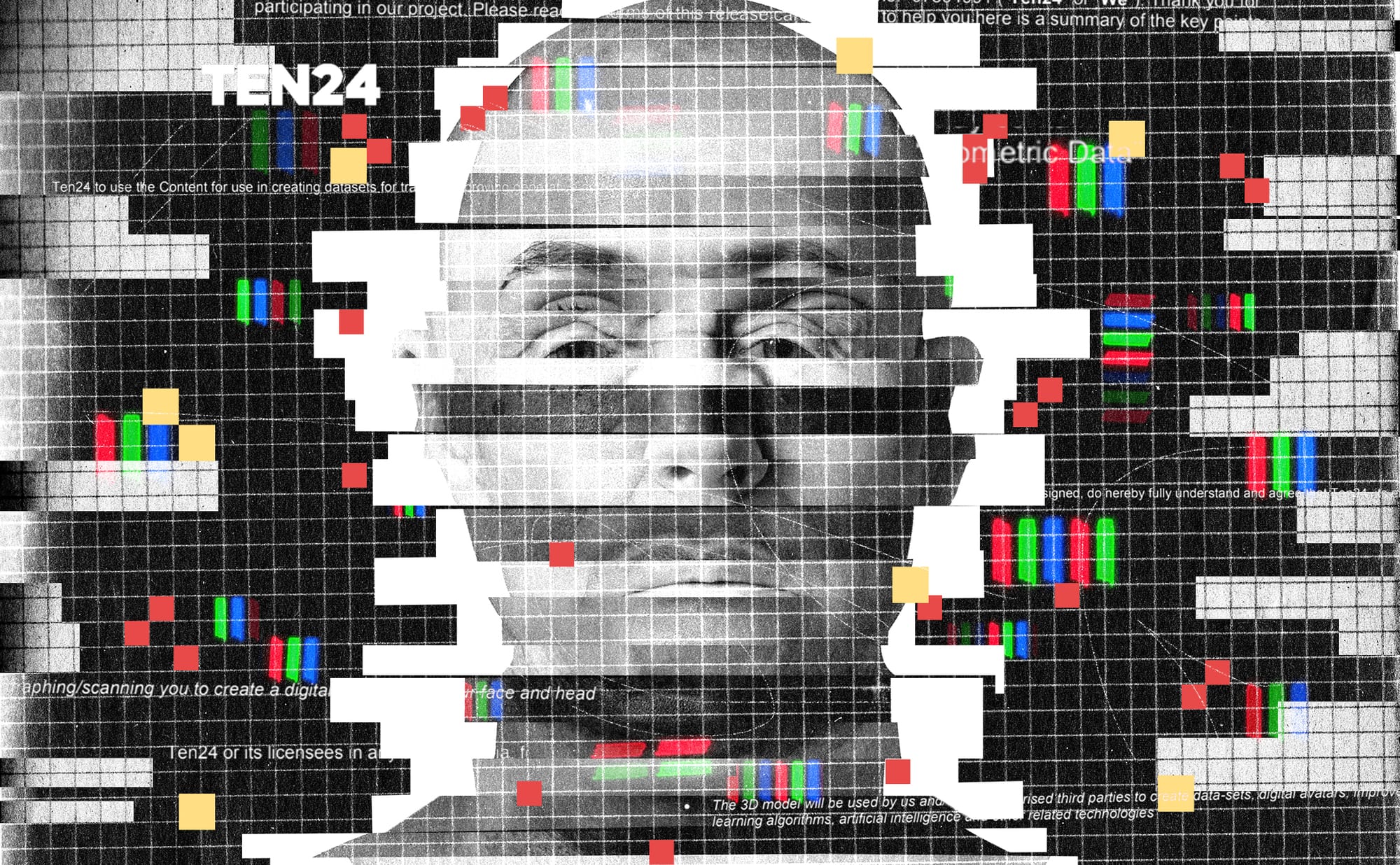

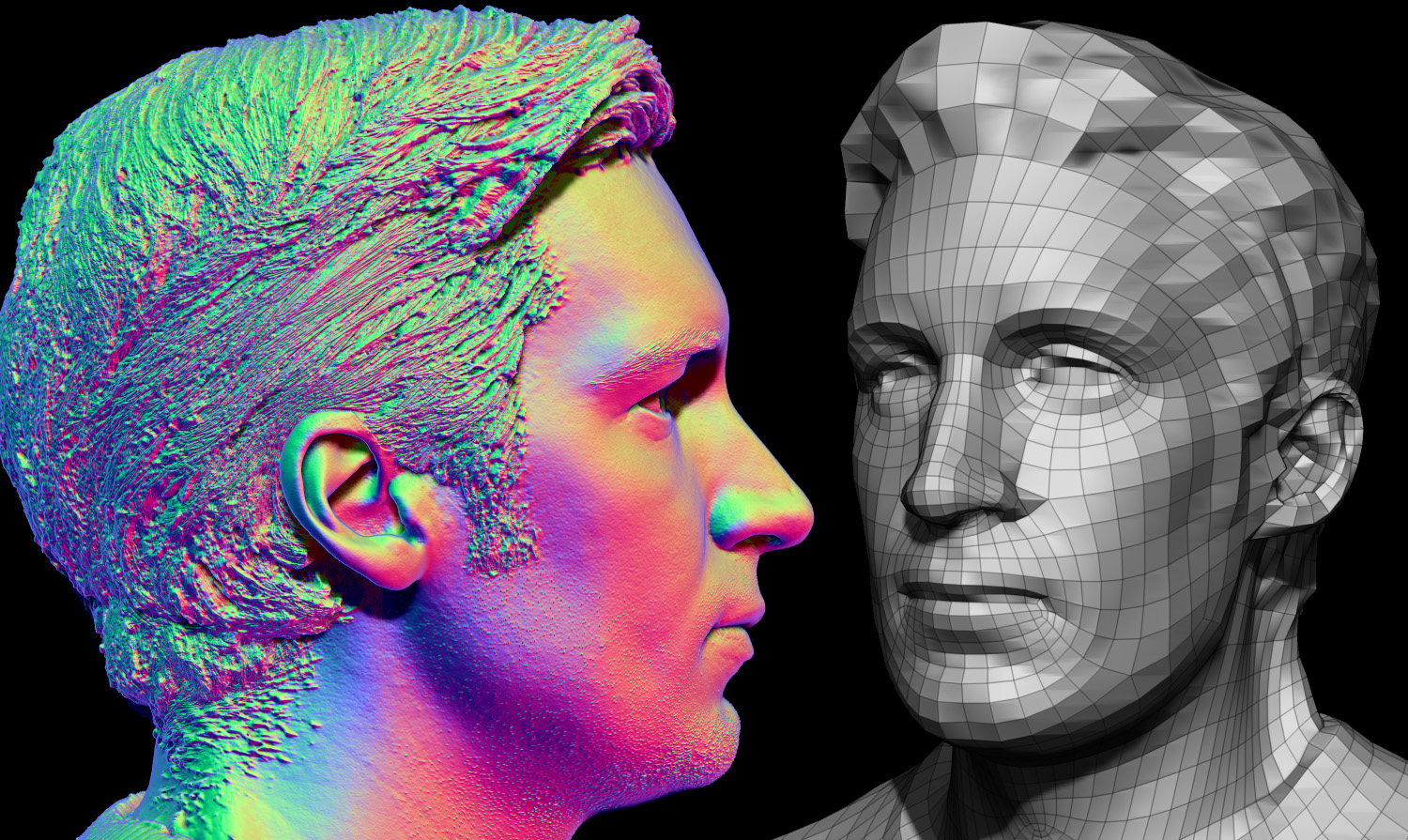

Image credit: Ten24

Ten24 is the most interesting Sheffield company you’ve never heard of. Their clients include Facebook, Apple, Boots and the NHS — not bad for a business that only employs nine members of staff. Their speciality: taking incredibly detailed photos, mostly (though not exclusively) of faces and bodies, then turning them into hyper realistic 3D digital models. These have been used for everything from creating overweight mannequins for hospital anatomy training to providing skin tones for makeup developers.

But the sector they’re really pitching to is gaming. Once upon a time, gaming companies would build their heroes from scratch. No-one would mistake the angular features and flat textures of 90s video game characters for actual people. But now, gamers expect hyper-realism — to be able to see the lines of the palm and each hair in the eyebrow of their characters. Building something this detailed would take masses of time. Wouldn’t it just be easier to take ultra-detailed photos of a real person instead?

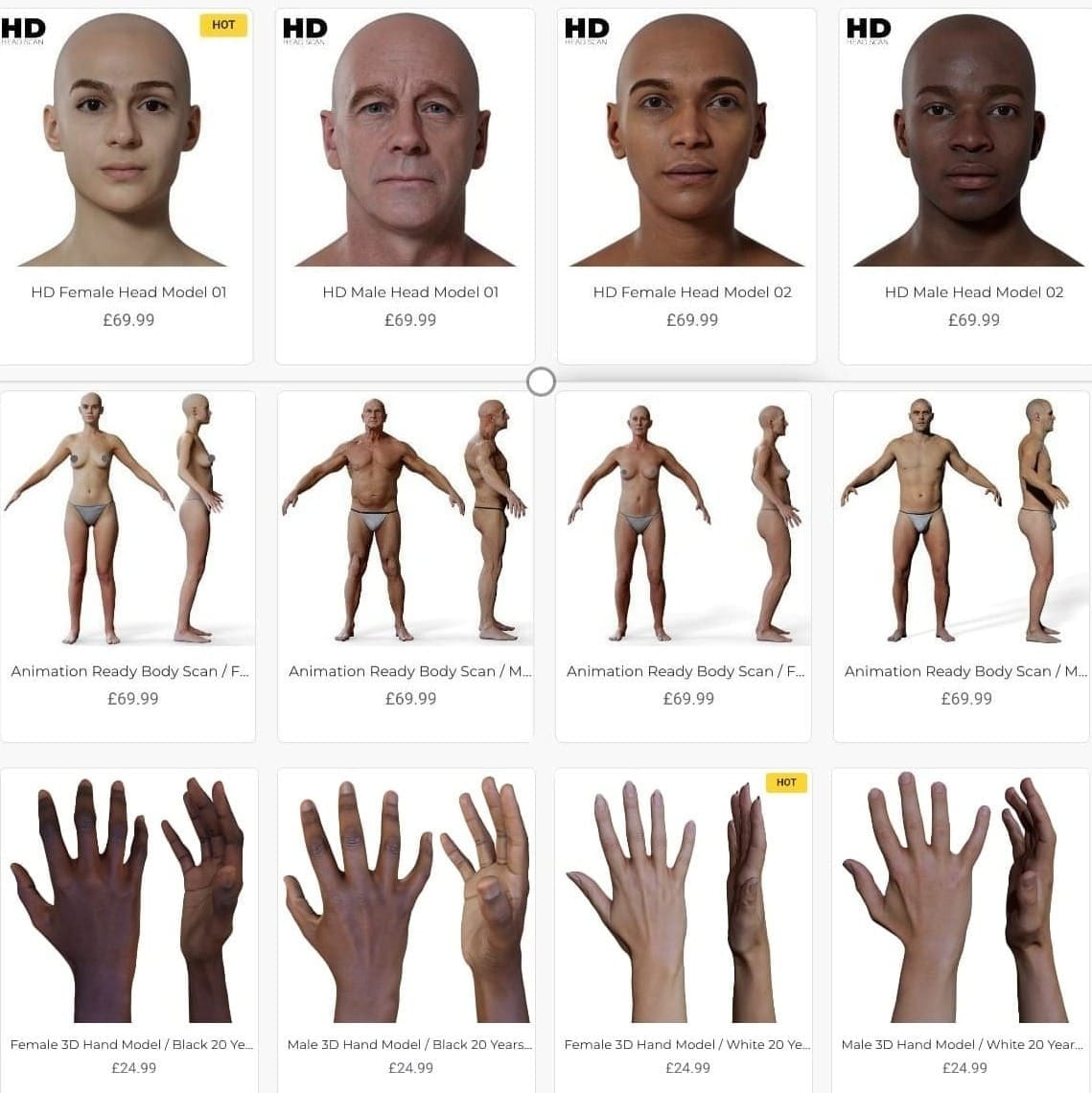

Ten24 has spent seventeen years doing exactly that. They were the first company to invest in this kind of technology (though others have since followed suit). A visit to their online scan store is a somewhat unsettling experience. Rows of faces, all bald-headed, on sale for £69.99 each. “Bundles” of lifelike digital bodies, wearing next to nothing. A hands section, a feet section, a teeth section. There are options to filter the cyberflesh for age, gender and ethnicity.

The images in the public store are taken from models — members of the public won’t start turning up there. But the faces captured in the Orchard Square Sapiens shop will probably be sold direct to the gaming industry. Your reward, for conveying such irrevocable permissions over your visual likeness, is £40.

The idea behind the project — and the reason it’s been given almost £350,000 to set up shop by the government — is to improve diversity and representation in computer games. According to one study, nearly 80% of main characters in video games were male and almost 55% of them were white. Sapiens is designed to right that wrong. In one year they hope to scan 10,000 everyday Sheffielders, providing games makers with a much wider range of faces for their characters.

So is Ten24 a Sheffield business success story that should be celebrated, doing important work to improve diversity? Or is the whole thing frankly a bit sinister? And, if you could do with forty quid — should you sell?

Ten24’s office in Kelham Island is a gamers’ paradise. Rows of IKEA kallaxes are stocked with 1980s games consoles, Warhammer mechs and lego models. Chunky computer towers gently pulse through the colours of the spectrum. Sci-fi film posters hang on the exposed brick walls.

Its founder, James Busby, sits in front of a vast screen. A dry-witted Belfast native in a grey hoodie and jeans, he’s showing me just how detailed the pictures Sapiens collects are. He pulls up the head of an expressionless woman, then zooms in close on her lips, then closer again. I can see the chapped skin, the minute lines were the flesh folds, the many shades of pink/orange/red. Forensic feels like too weak a word for the level of detail that’s been captured. So given he’s collecting such a large dataset of local faces, will the next generation of video game characters all be based on Sheffielders?

‘They already are’, Busby laughs. Ten24’s scans of models have been used in Final Fantasy and Halo, as well as TV shows like Doctor Who. And Busby doesn’t just dish it out — he’s perfectly happy to put himself in the scanner too. He’s appeared as Volo in Baldurs Gate 3, and a drowned giant in the Netflix show Love, Death & Robots. (After our interview, I look this up, and it’s a little eerie to suddenly see him beached on my screen, in a level of detail I couldn’t perceive even when I was sat a metre away from him).

I ask Busby about how well Sapiens is doing at getting a diverse group of people through the door. He tells me that so far there’s roughly a 50/50 split between white people and other ethnic groups. They’ve attracted slightly more women, probably because ‘the beard thing’s an issue’. (The scan requires you to be clean-shaven.) The oldest participant so far is 98 years old.

The demographic they’ve struggled with is East Asians. There’s a lot of Chinese students in Sheffield, so this can’t be due to them not being here. But, being Taiwanese myself, I wondered if our culturally–instilled fear of surveillance by the CCP might be a significant part in why they’re avoiding it.

The author in the scanner. Image: Ten24

Sheffield certainly has a diverse population, but it’s not representative of humanity in its totality. That’s where the next step of Ten24’s plan comes in.

‘Human faces are basically all the same,’ Busby says. ‘The only [difference] is muscle tissue, fat, and things like that... Once you have enough people, you can essentially infer more or less any face’. So even if only a couple of hundred East Asians get scanned, that — plus all the information on face shapes from the rest of the Sapiens project — should give enough to model and create a wide range of plausible faces.

But where will my face end up? And — more to the point — what could a character that looks exactly like me, down to the precise map of my freckles, end up doing in a video game?

Ten24 provide two guarantees: firstly, they won’t give your face to any government organisation. And secondly, that your image won’t feature in any sexually explicit content. ‘We get approached by porn companies all the time’, Busby says, but they wouldn’t go near that. (‘It’s a horrible industry’, he comments.) In any contract where they sell digital models they have an extremely detailed list of what exactly falls under ‘sexually explicit’ and can sue anyone who violates it.

Nonetheless, it’s not completely watertight. When I press Busby on how effectively they can monitor the end use of your image, he pauses. ‘If I say this, it’s gonna sound bad, but you cannot guarantee that with anything’. While the gaming companies that buy up the data are highly unlikely to take the legal risk of breaking that contract, there’s always a chance someone else takes that image from the game and uses it for less wholesome ends.

Outside of those two guarantees? Could I turn up as a serial killer? A Nazi commandant? ‘So, that could happen, yeah’, Busby confirms. ‘You might be a Nazi, but… that’s the nature of video games unfortunately.’

That risk isn’t huge. If Sapiens hit their 10,000 target, your odds of showing up as someone evil are pretty slim. And anyway, it’s more likely gaming companies will use a mix of people to create ‘composite’ characters — blending different people to get the desired effect.

And this, actually, is the Sapiens end game. As with everything, AI is coming for video game character creation. Bodies are easier, but faces are complex and it needs lots of real ones to train on. Once it has them, there’ll be no need to take hyper-realistic photos. The industry James Busby and his colleagues essentially invented will cease to be, all within the span of about two decades. ‘We’re destroying our own company, basically,’ Busby says with a smile. ‘We started it, so we’re going to end it.’

The final product, he speculates, would be something that allows a gamer to upload an image of their face, and instantly be turned into a lifelike avatar in a game. You could become the Sole Survivor in Fallout 4, or dribble past Messi in the latest FIFA. It's a big step up from choosing from eight available hair colours for your Nintendo Mii.

The many faces of James Busby. Clockwise from top left: In the Ten24 office; as Volo in Baldur's Gate 3; in the 3D scan store; and as the drowned giant in Netflix's Love, Death & Robots. Images: The Tribune, Larian Studios, Ten24, Netflix.

Busby says he has ‘no idea’ how much they will get for their dataset, and that they haven’t really worked out how best to commercialise the data. A surprising admission, but he’s someone who clearly identifies more as a gamer than a businessman. But when I press him on the morality of what he’s doing, he pushes back. ‘If we don’t do this, someone else will do it. And they probably will do it somewhere where there is no GDPR [and] no rights.’

One final question for Busby before we go. He’s been doing the job for long enough that he knows the kinds of faces people want to buy. So what, from a biometric point of view, does beauty look like?

‘I've scanned 10-15,000 people in my career, and yeah, you sort of start to recognise it,’ Busby says. ‘You can definitely tell people who will be photogenic, and it’s not necessarily the people you think it is’. What are the common factors? ‘It seems to be big eyes, big lips, an interocular distance [that’s] pretty average. Not a small nose and not a big nose either. And then jaw line is really, really important. So yeah, if you get all those things, you kind of hit the beauty marker.’

So should you sell your face to Sapiens? Indeed, would I have gone if it wasn’t for an article? Hard to know, but it’s been almost two weeks since I traded my biometric data for cash, and it hasn’t exactly been playing on mind.

Perhaps it’s a generational thing. I grew up on the internet, and from when I was ten up until I was a young adult, I treated it as if it were a diary, plastering my experiences all over it. (Granted, I did create and deactivate at least four separate Twitter accounts — all of them with over ten thousand tweets — during this time). My digital image is already out there in many forms.

If I was one of only a few people who had their scan done, I’d be a little more on edge. But given how many they expect to come through the door, my anxieties are slight; there’s safety in numbers. And anyway, more and more information is being gathered about us all the time — often without consent, or recompense. At least this way I got forty quid for it.

Additional reporting by Daniel Timms. You can find out more about the Sapiens project here.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.